75 years after the publication of the Beveridge report, LSE Festival Beveridge 2.0 (Mon 19 Feb – Sat 24 Feb 2018) offers a week of public engagement activities exploring the ‘Five Giants’ identified by Beveridge in a global 21st-century context. Tickets to all the events, which are free and open to all, can be booked here.

On Tuesday 20 February 2018, LSE hosted a ‘Citizen’s Basic Income Day’, including the LSE Festival evening event, ‘Beveridge Rebooted: A Basic Income for Every Citizen?’: listen to the podcast here. Ahead of the discussion, panellist Dr Malcolm Torry discusses his forthcoming new book on the topic, Why We Need a Citizen’s Basic Income, and how it builds on his previous works, including Money for Everyone: Why We Need a Citizen’s Income.

LSE Festival Beveridge 2.0 Preview: ‘Why We Need a Citizen’s Basic Income: A New Edition or a New Book?’ by Malcolm Torry

Why We Need a Citizen’s Basic Income will be published on 1 May 2018. It can be pre-ordered now from Policy Press.

Why We Need a Citizen’s Basic Income will be published on 1 May 2018. It can be pre-ordered now from Policy Press.

A Citizen’s Basic Income (sometimes called a Basic Income, a Citizen’s Income or a Universal Basic Income) is an unconditional and nonwithdrawable income for every individual. Everyone of the same age would receive the same amount, every week or every month, no matter what their income, wealth, employment status, household structure, etc. Children would receive less, younger adults might receive less than working-age adults and older people might receive more; the amounts paid would be uprated each year, but otherwise the amount would never change. The payment would begin at birth, and it would cease at death.

Ever since the late eighteenth century, and possibly before that, this idea has emerged into public consciousness and then disappeared into obscurity. A brief flurry of activity 35 years ago prompted a small group of us to form the Basic Income Research Group – now the Citizen’s Basic Income Trust – and then the Basic Income European Network (BIEN: now the Basic Income Earth Network) to promote research and debate, so that the idea wouldn’t disappear entirely, and so that the next time there was an upswing in interest, there would be expertise and literature available to facilitate an intelligent discussion.

By 2011 no book-length general introduction to Citizen’s Basic Income had been published for twenty years, so I wrote Money for Everyone: Why We Need a Citizen’s Income (Policy Press, 2013). We decided to put detailed research results in an online appendix because we believed that the figures would go out of date much faster than the book. We were wrong. The figures for a feasible Citizen’s Basic Income scheme haven’t changed very much, but the debate has.

In response to demand for a shorter introduction to the topic, I subsequently published 101 Reasons for a Citizen’s Income (Policy Press, 2015); and then, in 2016, Policy Press suggested that a new edition of Money for Everyone might be required. I agreed, so set about updating the book. I quickly realised that the whole of Money for Everyone would have to be rewritten.

Money for Everyone was written to facilitate the debate as it was six or seven years ago, and it answered the question: ‘would a Citizen’s Basic Income be a good idea?’ There were chapters on the history of the UK’s benefits system and of Citizen’s Basic Income. Further chapters compared the UK’s current system and one based on a Citizen’s Basic Income in relation to administration, employment incentives, household structure, efficiency and dignity. I then asked whether people would still seek employment, and decided that many people would be more likely to do so than they are now because a Citizen’s Basic Income would not be withdrawn as earnings rose, whereas means-tested benefits are. Another chapter asked whether a Citizen’s Basic Income would reduce poverty and inequality (in general yes, but the answer depends to some extent on the tax and benefits changes that would accompany the implementation of a Citizen’s Basic Income). The following sections were about citizenship and who should receive a Citizen’s Basic Income; whether the country could afford a Citizen’s Basic Income; and whether the idea cohered with a variety of political ideologies. The final two chapters were about alternatives to Citizen’s Basic Income, and about the social problems that a Citizen’s Basic Income would not solve.

By 2016 the question ‘would a Citizen’s Basic Income be a good idea?’ was still being asked, but two other questions were if anything more prominent: would a Citizen’s Basic Income be feasible? And how would it be implemented?

In 2014 I had been asked to write an entire book on feasibility: The Feasibility of Citizen’s Income (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). This listed seven different feasibilities: administrative; psychological; behavioural; political; policy process; and two kinds of financial feasibility: fiscal feasibility and household financial feasibility. In today’s financial climate we have to assume that there will be no additional public funds available, so to be feasible a Citizen’s Basic Income would have to be paid for by rearranging the current tax and benefits system. Because under those circumstances every household net income gain would imply a net income loss for another household, it would be essential to ensure that no household would experience unsustainable losses at the point of implementation, and in particular that no low income household would suffer a net loss. The book concluded that there were Citizen’s Basic Income schemes and implementation methods that could satisfy the feasibility criteria.

Given the current state of the debate, it was essential that the new edition of Money for Everyone should contain substantial amounts of material on both feasibility and implementation. In 2016 the Institute for Chartered Accountants held a consultation on the implementation of Citizen’s Basic Income and asked me to write a report. This became the basis for the chapter on implementation in the new edition. The Feasibility of Citizen’s Income became the basis for the chapter on feasibility.

It was also clear that it had been a mistake to relegate research results on a feasible illustrative scheme to an online appendix to Money for Everyone. Many of the questions that I was being asked related to affordability, net income losses for low income families, poverty and inequality indices and marginal deduction rates (the total rates at which additional earned income is reduced by taxation and benefits withdrawal). It had also become essential to include results from microsimulation research in a substantial appendix in the book itself.

And of course, much of the book needed updating and expanding. There have been more pilot projects and experiments to report on in India, Finland, Kenya, Germany, Scotland, Canada, the USA and the Netherlands, and it was now vital to include a chapter that responded to objections to Citizen’s Basic Income. With so much new material, something had to go: so no longer will the reader find a lengthy history of the UK’s benefits system or a detailed exploration of the notion of citizenship.

Because the publication is perhaps more a new book than a new edition, Policy Press has given it a new title, Why We Need a Citizen’s Basic Income (with a subtitle relating to feasibility and implementation), as well as a new cover featuring the familiar pair of wallets: a reference to Money for Everyone. If the Citizen’s Basic Income debate continues to evolve as rapidly as it is evolving now, then perhaps there will need to be another new edition in 2021.

A significant element in the continuing discussion will be the Citizen’s Basic Income day at the LSE on Tuesday 20 February as well as the LSE Festival debate in the evening, ‘Beveridge Rebooted: A Basic Income for Every Citizen?’. The morning will bring together experts on political feasibility, funding methods and costings; the afternoon will gather speakers from pilot projects and experiments around the world. In the evening, Professors Philippe Van Parijs and John Kay will debate the motion: ‘This house believes that if the Beveridge Report were being written today then it would have recommended a Basic Income’. The answer to that question might, of course, be different from the answer to the question: ‘do we need a Citizen’s Basic Income?’

Dr. Malcolm Torry has been Director of the Citizen’s Basic Income Trust since 2001 (and was Director before that between 1988 and 1992); he is a Visiting Senior Fellow in the Social Policy Department at LSE; and he is General Manager of BIEN, The Basic Income Earth Network. He is the author of Money for Everyone: Why We Need a Citizen’s Income, 101 Reasons for a Citizen’s Income, The Feasibility of Citizen’s Income and a new edition of Money for Everyone out later this year with a new title, Why We Need a Citizen’s Basic Income. Malcolm is a priest in the Church of England, and from 1980 to 2014 served in full-time posts in South London parishes. He has written extensively on the characteristics and management of religious and faith-based organisations.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Why We Need a Citizen’s Basic Income will be published on 1 May 2018. It can be pre-ordered now from Policy Press.

Why We Need a Citizen’s Basic Income will be published on 1 May 2018. It can be pre-ordered now from Policy Press.

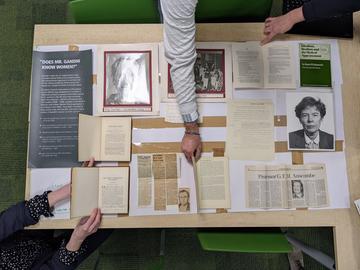

Image Credit: (

Image Credit: (

2 Comments