In The Circulation of Anti-Austerity Protest, Bart Cammaerts examines how protest circulates in society, drawing on an investigation into the UK anti-austerity movement following the 2008 financial crisis. Proposing the ‘circuit of protest’ as a novel theoretical framework, this engaging and informative book offers rich insights into how social movements engage with communication technologies and processes, finds Sabrina Wilkinson.

The Circulation of Anti-Austerity Protest. Bart Cammaerts. Palgrave Macmillan. 2018.

From the rise of left-wing politician Jeremy Corbyn to strikes in the higher education sector, there is no shortage of figures or events in recent news emblematic of a resistance to austerity measures in the United Kingdom. Members of the British public have pushed back against deep cuts to public spending, whether this is at the ballot box, on the picket line or – as is the empirical focus of Bart Cammaerts’s meticulously researched book, The Circulation of Anti-Austerity Protest – in grassroots social movements. At the heart of these protests against austerity, Cammaerts suggests, are two core discourses: a renewed politics of redistribution and ‘real democracy’. To that second notion, he writes: ‘democracy, as it functions today, is viewed more and more as a broken system, controlled by an unrepresentative and distant elite […] not acting ‘‘in accordance with the views of the citizens’’’ (50).

Drawing on an investigation into the UK anti-austerity movement after the 2008 financial crisis, Cammaerts’s aim is to develop a greater understanding of how protest circulates in society, and the implications of this process. To do so, Cammaerts relies on a novel theoretical framework termed the ‘circuit of protest’, which involves four instances where media and communication technologies are incorporated into social movements. These moments are: the production of movement frames, discourses and collective identity; the movement’s internal and external communicative practices; mainstream media representations of the movement; and the reception of the movement’s discourses and frames by non-activist citizens.

Relying on methods including surveys, content analysis, focus groups and in-depth interviews, The Circulation of Anti-Austerity Protest walks the reader through an application of the circuit of protest to the involvement of several key groups in the UK anti-austerity movement: namely, UK Uncut; the National Campaign Against Fees and Cuts; and the Occupy London Stock Exchange. Cammaerts’s findings relate to each moment within the framework as well as to what he terms the mediation opportunity structure: ‘the power dimension at the level of the production, circulation and reception of meaning’ (30).

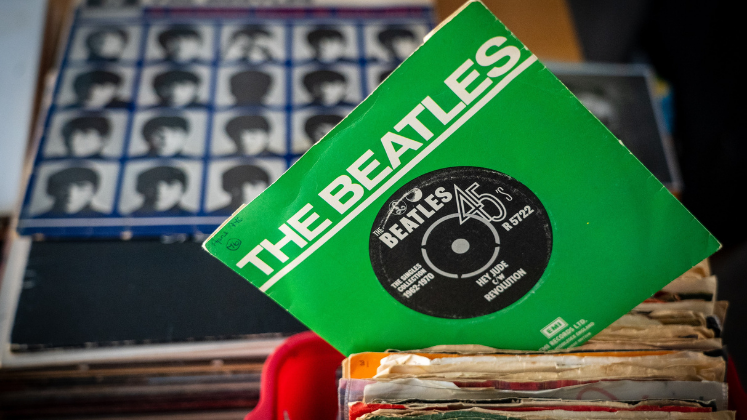

Image Credit: Occupy London Stock Exchange Protest, 2011 (Valters Krontals CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: Occupy London Stock Exchange Protest, 2011 (Valters Krontals CC BY 2.0)

It is through this framework that Cammaerts reveals some of his most salient empirical findings in all four ‘moments’ of the circuit of protest framework. During the ‘moment’ of the production of anti-austerity movement frames, the author outlines the ways that activists framed the protests as pure common sense and, accordingly, without an ideology. With regard to the movement’s internal and external communicative practices, Cammaerts highlights the many contradictions between social movements’ reliance on mainstream media and technologies to achieve their aims and their resistance to many of the practices promoted by these platforms, such as digital exploitation. Within mainstream representations of the anti-austerity protests in the UK, the author points out, amongst other things, the disparate representations of ‘civic’ student protestors and those who are disruptive, corrupted and sometimes violent. With respect to the reception of the anti-austerity protests’ discourses and frames by non-activist citizens in the UK, Cammaerts finds both that the movement resonated with the public in a variety of often contradictory ways and also that it evoked ‘a deep sense of frustration and powerlessness […] by many citizens’ (177).

Broadly, Cammaerts’s insights are compelling because they shine a light on the many tensions between the ways that activists use traditional and contemporary media to promote their cause against the challenges posed by corporate and state repression. As scholars in the discipline of media studies have long pointed out, communication processes are not homogenous activities but ones fraught with tensions between various powers, albeit unequal ones. Cammaerts also highlights the extent to which neoliberal forces are in some ways left unaddressed by the anti-austerity movement. The author finds that by abstaining from identifying an ideological position, the social movement operated within the neoliberal framework rather than against it: ‘mere political momentum, which clearly was present in the post-2008 period, is not enough to break a movement or denaturalize the hegemony of neoliberalism’ (168).

Although Cammaerts’s empirical findings are thorough and engaging, it is his theoretical contribution to the study of protest that makes this work stand on its own. In an area of research such as social movement studies where the insights provided by the examination of media studies have often been placed at the periphery (5), Cammaerts offers a coherent framework that others may apply to investigate the role of communication processes and technologies in a variety of other political struggles. With the increased connectivity provided through networked technologies in nearly all aspects of social and political life, theoretical frameworks that position these tools as a central element of study, rather than an afterthought, are critical. As the author writes, ‘contentious actions are […] not only fought on the street, but also in the public sphere, in the mainstream media, and online as well as offline’ (5).

While beyond the scope of Cammaerts’s endeavour here, further research may do well to examine the implications of contemporary media and communications policy at various moments in the circuit of protest. For instance, it may be useful for future studies to incorporate questions such as: what do media and communications policies mean for how activists engage in communications within and surrounding social movements? And what are the implications of the type of technologies audiences use to consume information and news about protests? Individuals who rely on a public broadcaster and have limited access to broadband internet and cable networks due to prohibitively high prices, for example, would surely have different media consumption habits than they would if these technologies were regulated to make them affordable to the widest available public.

Recognising the importance of media and communications policy that is actually in the public interest reminds this reviewer of the very example that Cammaerts uses to begin his exploration into anti-austerity protest group, UK Uncut: the settlement made between mobile operator Vodafone and Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs Office (HMRC) that was revealed to have cut the provider’s tax bill from £6 to £1.3 billion. While Cammaerts’s illustration is an issue of taxes rather than consumer prices, this instance is at least emblematic of the often too-close relationships held between powerful communications organisations and governments.

In sum, The Circulation of Anti-Austerity Protest is an engaging and readable contribution to the field of media and communications and to social movement studies. It offers rich empirical insights into how various groups involved in anti-austerity protests in the UK—ranging from activists to audiences—use communication technologies as well as a theoretical framework that others can apply to the study of social movements, organised for this end or any other. Accordingly, this book will surely be an informative read for students and researchers interested in these disciplines, as well as activists and media practitioners.

Sabrina Wilkinson is a doctoral researcher in Media and Communications at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her dissertation focuses on the politics of internet policy in Canada. She is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book: