In Athens and the War on Public Space: Tracing a City in Crisis, Klara Jaya Brekke, Christos Filippidis and Antonis Vradis merge textual and visual material to focus on Athen’s public space and its socio-spatial dynamics, attempting to grasp, however momentarily, the ever-moving, multifaceted and violent consequences of crisis. This is a valuable intervention that critically addresses the key issues faced by both a society and its space in deep crisis and experiencing radical change, writes Panos Bourlessas.

Athens and the War on Public Space: Tracing a City in Crisis. Klara Jaya Brekke, Christos Filippidis and Antonis Vradis. punctum books. 2018.

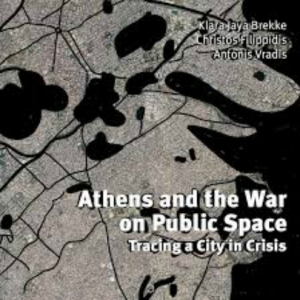

Image Credit: Athens (Vincent W.J. van Gerven and Klara Jaya Brekke)

Image Credit: Athens (Vincent W.J. van Gerven and Klara Jaya Brekke)

Look at the picture above: an urban fabric. Building blocks, boulevards, squares, streets, green areas, all forming a complex geometry of concrete so familiar to the modern viewer-consumer of satellite imagery. Yet, this urban fabric seems to be less static than others. Streets turn into rivers, lakes emerge and expand filling the city with dark patches that tend to occupy a bigger and bigger surface. The geometry of concrete thus acquires a liquid state. And so, the city changes. Now imagine the urbanites that live in this city: commuting, walking, consuming, working, hating, loving. Everything within this liquid state and in-between these dark moving patches —or, worse, underneath them. How does this urban life of constant and radical change unfold, and, eventually, how are the effects of such transformations experienced daily?

In their book Athens and the War on Public Space: Tracing a City in Crisis, Klara Jaya Brekke, Christos Filippidis and Antonis Vradis attempt to give us a response, bringing evidence from the city that has been at the epicentre of the global financial crisis: namely Athens, Greece. Merging together textual and visual material, the authors focus on the city’s public space and the socio-spatial dynamics therein in order to grasp (just for a moment and only on paper) the ever-moving, multifaceted and violent consequences of crisis. For them, public space functions as a ‘light-sensitive surface’ (14) on which the top-down decisions of financial institutions materialise. However, and paradoxically, the ‘light’ of crisis that reaches the surface has a darkening effect on the public space and the subjects placed therein —for subjects are ‘light-sensitive’ too, particularly the most vulnerable.

At the beginning of Athens and the War on Public Space, Brekke provides a timeline, tracing a variety of events that together have given shape to the so-called Greek crisis from 2008 to 2014. This not only situates the book within a temporal, rather than solely spatial, framework, but also highlights the role of memory in understanding the multifold social magnitude of the crisis, its complex spatial expressions as well as the interrelations of several actors and institutions that, albeit located faraway, cast their effects on Athenian public space. Ross Domoney’s images illustrate the affective aspects of the timeline and the compact memory it embodies.

At the beginning of Athens and the War on Public Space, Brekke provides a timeline, tracing a variety of events that together have given shape to the so-called Greek crisis from 2008 to 2014. This not only situates the book within a temporal, rather than solely spatial, framework, but also highlights the role of memory in understanding the multifold social magnitude of the crisis, its complex spatial expressions as well as the interrelations of several actors and institutions that, albeit located faraway, cast their effects on Athenian public space. Ross Domoney’s images illustrate the affective aspects of the timeline and the compact memory it embodies.

The structure of the rest of this review is not based on the book’s sequence of chapters, but rather on the two general types of public space that the authors focus on to compose a more complete image of the ‘war’ of the book’s title. These two types comprise the overground and the underground Athenian public space, each of which allows different dynamics to unfold and each of which relates to different subjectivities.

In the book, overground public space—namely the archetypal spaces of streets and squares—is where the effects of the crisis on the city’s ‘alien subjects’ are traced and analysed. Located therein, the (vulnerable) bodies of these subjects are exposed to certain socio-spatial practices and discourses that affect them dramatically. The crisis transforms Athenian public space into the terrain par excellence where the city’s biopolitics play out (Filippidis, 53-102). Precisely through humanitarian reasoning, normative discourses present alien subjects, such as migrants and female sex workers, as ‘ill bodies’ that render the city centre ‘ill’ too. In this spatial-hygienic combination, the authorities construct the ‘biological enemy within’ (82): the whole nation’s organism is threatened by the ‘illness’ carried by alien subjects in the capital’s public spaces. Thus, police are called to —medicalised— action; anti-migratory operations and raids are used to recover the city’s valuable ‘health’ so that the nation can be protected overall.

A documentation of less systemic racist attacks, either by police officers or members of the extreme-right Golden Dawn party, stresses the legitimising effects of such discourses and practices as well as their spatial range that expands far beyond Athens’s city centre (Brekke, 103-107). Nevertheless, along with its biopolitical functions, Athenian public space serves too as the terrain whereon the crisis-imposed ‘state of emergency’ manifests itself spatially. Filippidis describes the anti-squatting operations that took place between late 2012 and early 2013 as spatial operations through which the state of emergency is performed, both discursively and practically (137-70). This discourse-practice nexus establishes a new paradigm for the city centre: one of its securitisation and subsequent militarisation through the presence of the police force, thus transforming central Athens into a ‘testing lab’ (156) for a new dogma that targets migrant and refugee subjects in order to rebuild the Greek national identity.

On the other hand, underground public space—namely the city’s metro system—is where the effects of the crisis on the more ‘familiar subjects’ of Athens can be traced. Vradis provides an experiential account of the public space par excellence for the Athenian ‘commuter-subject’ (109-17, 121). In the metro carriage, an uncomfortable silence plays out. In the metro carriage, this silence becomes the crisis’s newly imposed atmosphere, wherein the passengers are altogether immersed: waiting for something to be said; waiting for something to be done. Presenting the underground public infrastructure as an apparatus of a certain monotonous rhythmicity, Vradis shows how a synchronisation of the city, its bodies and the crisis may produce affective and alienating effects not (only) for the ‘Other’, but also for more familiar subjects —like ‘us’ (119-35). Excellent black-and-white pictures from Athens’s ISAP metro line artfully complement the text whilst emphasising an urban decaying materiality that corresponds to the crisis, its atmosphere and the embodied subjectivities placed therein.

Overall, Athens and the War on Public Space is a valuable read for a number of reasons. It critically addresses key issues of both a society and its space in deep crisis and experiencing radical change, especially for its most vulnerable; it constructs biopolitical and non-representational registers that are so absent in mainstream contemporary analyses of the Athens city centre; and it brings together textual and visual material in an organic, often affective, manner that successfully avoids aestheticisation.

Amongst the book’s possible limitations is that, as the authors note themselves, their focus is on a ‘small unit of space’ (14), leaving aside not only (more or less public) spatialities that, albeit less central, do matter in how the crisis is experienced, but, most importantly, spatialities that emerge in central public space in radically different ways. More precisely, whereas the crisis manifests itself as an ‘urban dystopia’ for the most vulnerable, it simultaneously shapes an ‘urban utopia’ for the most privileged. In Athens, new spaces of consumption and the increasing touristification of the city centre and central neighbourhoods invite social practices, bodies and materialities that result in an excessively refined, stylised and depoliticised public space devoted to consumerism and its hedonistic logic. Such spatialities and dynamics ought to be considered if we are to fully grasp the complex and paradoxical dimensions of a city life in crisis. For ‘urban dystopias’ and ‘urban utopias’ may stand side by side, in the same public space.

Now take a final look at the picture above. And note that the Acropolis, Athens’s most recognisable landmark—perhaps what, to many, makes Athens Athens—has disappeared below one of those growing dark patches that occupy the urban fabric. Without its fabled monument, Athens is less Athens, starting to resemble any city. Similarly, the critical evidence brought to the fore by Brekke, Filippidis and Vradis may not be limited only to the Athenian context, but can also be of relevance to other cities of our capitalist world, the latter’s current structural crisis becoming increasingly urban.

Panos Bourlessas holds a PhD in Urban Studies from the Gran Sasso Science Institute, Social Sciences Unit, L’Aquila, Italy (jointly awarded with the Scuola Superiore Universitaria ‘Sant’Anna’, Social Sciences, Pisa, Italy). Using multi-sited ethnographic methods, his doctorate research has focused on the homeless cultural geographies of central Athens, Greece, through the conceptual triptych of materialities-bodies-mobilities. A first outcome of his research has been published in the journal Mobilities.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments