In Heading Home: Motherhood, Work and the Failed Promise of Equality, Shani Orgad draws on interviews with educated, London-based women to explore their decision to leave their successful careers to become stay-at-home mothers. Delving into the profoundly ambivalent, contradictory and conflicting experiences and desires narrated by Orgad’s subjects, this book offers a compelling and essential analysis that makes a powerful argument for working on the social conditions that hold patriarchal power structures in place, writes Yvonne Ehrstein.

Heading Home: Motherhood, Work and the Failed Promise of Equality. Shani Orgad. Columbia University Press. 2019.

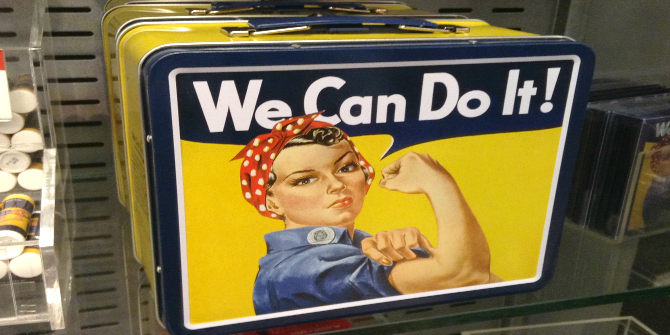

As Shani Orgad notes in her new book, ‘there is something shocking, or at least deeply puzzling, about the decisions made by women’ (3) in contemporary capitalist societies to head home and care for their children and families. In the light of western cultural myths of accomplished gender equality and messages that women can ostensibly ‘have it all’, the experiences of and media and policy discourses surrounding stay-at-home mothers call for exploration. Why, Orgad asks, ‘do educated mothers who grew up in a cultural and policy climate that champions women’s successful combining of motherhood and economic activity, and who can afford the help that would allow them to stay in paid employment, make this retrogressive “choice”?’ (4)

As Shani Orgad notes in her new book, ‘there is something shocking, or at least deeply puzzling, about the decisions made by women’ (3) in contemporary capitalist societies to head home and care for their children and families. In the light of western cultural myths of accomplished gender equality and messages that women can ostensibly ‘have it all’, the experiences of and media and policy discourses surrounding stay-at-home mothers call for exploration. Why, Orgad asks, ‘do educated mothers who grew up in a cultural and policy climate that champions women’s successful combining of motherhood and economic activity, and who can afford the help that would allow them to stay in paid employment, make this retrogressive “choice”?’ (4)

Building on her previous, extensive scholarship that explores constructions of motherhood and work across several media outlets, in Heading Home, cultural and media scholar Orgad undertakes the critical endeavour to unfold these entanglements. Drawing on 35 interviews with educated, London-based women who left their careers after having children, and five male partners who remained in paid employment, she juxtaposes these accounts against UK and US media and policy representations of women, work and family, skilfully interlacing the personal stories of mothers with cultural narratives in a compelling three-part analysis.

The author purposefully focuses on the experiences of privileged middle-class mothers. Explaining this choice with a rationale that is similar to Betty Friedan’s in her influential study of the American middle-class housewife of the 1950s, Orgad argues that ‘oppression can be experienced alongside privilege, that choice and inequality are not mutually exclusive’ (16). While this is an approach of ‘studying up’, the ways in which the complex interrelations between inequality, privilege, oppression and the continuing power of patriarchal institutions are negotiated is a structural matter that extends beyond the women that were interviewed for this study.

The first part of the book examines women’s exit from the workforce, which, as Orgad discloses, is frequently and contrary to the dominant cultural framing not a ‘free choice’, but a decision that is impacted by multiple factors such as ‘toxic work cultures’ and oftentimes partners’ family-unfriendly, high-powered jobs with long working hours. Yet, culturally manifest in the contemporary dominant ideal of the ‘balanced woman’, accomplishing a felicitous work-life balance is depicted as desirable and possible. It is against this benchmark of the balanced-woman figure that Orgad’s interviewees measure themselves — and feel fallible for not realising these convergent notions of career success, motherhood and femininity in their personal lives.

In the second section, Orgad lays bare the ambivalent constructions of motherhood in media and policy discourses, highlighting conflicting expectations of, on the one hand, being ‘good’ mothers who prioritise their children, and contributing to the economy and family income through active workforce participation on the other hand. Experiencing this as the judgmental voices of the government and media and also of their more immediate social environment including husbands and even their own mothers, the women interviewed by Orgad struggled against feelings of self-blame for having failed to live up to the markers of contemporary successful femininity. To make sense of their new roles as stay-at-home mothers aka family CEOs, they rechannelled their knowledge and skills as previous professionals in defence of an ‘identity that is entirely reliant upon being a mother’ (97).

Chapter Four in Part Two contrasts ‘public stories of motherhood’ and its current hyper-visibility in the cultural sphere with ‘private stories of wifehood’. In this fascinating account, Orgad reveals how women’s roles as wives are obscured through the contemporary emphasis on motherhood, and the apparent erasure of patriarchy: ‘motherhood’, she argues, ‘has ousted wifehood’ (114). The author demonstrates incisively that being a selfless (house)wife is an invisible and unpopular rather than habitable identity nowadays, where women are celebrated as educated, empowered and independent ‘workers and mothers, not wives’ (135). Despite the appearance of non-normative representations of ‘aberrant mothers’ in media sites such as television and the emergence of the internet as a platform enabling more diverse and complex cultural scripts about motherhood, the ‘private story’ of wifehood is one that remains untold.

While embracing popular narratives of motherhood, the women Orgad met were deeply invested in masking aspects of their lives that related to their identities as wives. Most interestingly, this ‘work of cover-up’ (106) was rendered possible through the collusion of their partners. Indeed, in Orgad’s study, participants and their husbands employed a range of strategies to silence women’s roles as wives; at the same time, these tools helped justify the gendered separation between the private home and public work life. For instance, drawing on competing tropes of ‘natural’ gender differences and egalitarian relationship ideals, one of the male study participants explained a rather uneven distribution of domestic and childrearing labour between himself and his wife using phrases such as: ‘That works for us. It feels balanced. […] She’s just better at it!’ (125).

As Orgad’s fine-grained analysis demonstrates, this ‘essentialist/egalitarian story’ sustains the ‘family myth’ (126) of an equal partnership and helps in dealing with difficult emotions that arise from living the gendered split between the disparaged sphere of the home and the valued productive sphere. Similarly, the author discusses how the women she interviewed distance themselves from domesticity and housewifery, while at the same time commending their husbands for their contribution to household tasks, in this way restoring old-fashioned, heteronormative setups.

The final part of the book deals with the future of work and gender equality. Here, Orgad carves out women’s optimistic hopes for their own reconnection to the public world of work as ‘mompreneurs’ who run their own business from home, and their belief in progress towards gender equality as an ‘organic, inevitable’ process (181). While the mompreneur fantasy operates as an individualising solution to the structural problem of harmonising childcare and paid work that only superficially serves as a remedy, ideas of maternal entrepreneurialism as bringing self-fulfilment and freedom from the constraints of nine-to-five employment still reverberated as ‘inarticulate desires’ (153) in the stories of the women Orgad met.

Orgad argues that women’s desires for social change are contained in the mompreneur figure and the evasive notion that ‘challenging inequalities is too daunting a project’ (181). Relying on women trailblazers and governmental initiatives, Orgad’s interview participants had a limited sense of their own agency and capacity to bring about change and fight inequality. For example, we meet 46-year-old Charlotte, a former lawyer, who gave up the opportunity to attend a promising job interview in person since the date clashed with a previously arranged family holiday. Why, asks Orgad, did so many of her interviewees ’draw a veil over their desires and avoid rocking the boat?’ (171) While the absence of agency in this and similar stories seems baffling, most saddening is the discouraging message they convey to their daughters: ‘Adjust to, don’t challenge the status quo’ (188).

The conclusion, however, is not sombre, but offers a way forward through a valuable discussion of the necessary, and desired, structural changes in the workplace and family, as well as in cultural and policy representations. In what Orgad calls ‘that conversation’, she advocates for the reconnection of the personal and the political in spaces that unmute the disappointment and rage she feels her interviewees were suppressing amid culturally prevalent notions of individual positivity, happiness and balance.

Heading Home is an essential book. Its significance lies in astutely analysing the contradictions and ambivalences of lived experiences and public discourses of motherhood, equality and work, an important task that is often neglected in media and cultural research. Orgad’s book tellingly evidences the force of cultural formations and their expansion into women’s psyches. While the book makes a powerful argument for working on the social conditions that hold patriarchal power structures in place, I was left wondering whether ’conversations’ in the workplace and in families can provide sufficient incitements to regain the spirit of collectively achievable social justice from pre-neoliberal feminist eras.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: (Uwe Baumann from Pixabay CCO).

This is a fascinating piece of work and I’m looking forward to reading this book. As someone whose children have grown up but who maintained a professional career through job-sharing, I would be really interested to see how these women feel in 10-15 years, and how they tell their story to their own daughters. Motherhood is frequently presented as a job for women of school-age children but parenthood is for life and the consequences of decisions made while looking after babies and toddlers will reverberate throughout their lives and those of their children.

The consequences of decisions made are always felt by the children. Whichever they are. As they are felt in the marriage.

The economic consequences felt by a stay at home mother-home- carer has one impact for sure: no salary and no pension.. This is how society considers the occupation of caring for children and home (this usually includes husband and marriage too).

So…

A job for salary and pension then?

How to organise that?

What “mother substitute” to have?

What home and house organisation?

What is best for children and family?

What is best for the woman?

Why is it a good idea to go against maternal instinct of care, or is it not?

What is the effect on the children of decisions with different factors that limit in fact always “choice” ?

Not data from the past because women did all and could not complain. . ?

Many questions that need a follow up book.