In Russia, BRICS and the Disruption of Global Order, Rachel S. Salzman offers a new study that seeks to understand the driving forces behind the coalition that is BRICS – formed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – and dispel the misconceptions that surround it. The book sheds unique light upon this contested and under-researched group of nations and highlights the transient nature of the system of global governance, writes Erdem Lamazhapov.

This book review has been translated into Mandarin by Magnus Obermann / 李云龙,LSE-PKU MSc in International Affairs (LN814, teacher Dr Lijing Shi) as part of the LSE Reviews in Translation project, a collaboration between LSE Language Centre and LSE Review of Books. Please scroll down to read this translation or click here.

Russia, BRICS and the Disruption of Global Order. Rachel S. Salzman. Georgetown University Press. 2019.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

In the eyes of a realist reader endemic to the Western security establishment, the narrative presented by Rachel S. Salzman in Russia, BRICS and the Disruption of the Global Order may appear as nightmarish, perhaps even unfathomable. It is a story of a plot to overturn the stable world order, a rebellion against the post-Cold War institutional alignment. As such, the book brings the reader that adheres to this notion of Euro-Atlantic supremacy to understand the driving forces that bind the coalition that is BRICS – namely, Brazil, Russia, India and China, joined in 2010 by South Africa – and dispels any misconceptions that surround it. Yet, paradoxically, it may reaffirm many readers’ belief in the stability of the Euro-Atlantic global order.

Salzman takes up the constructivist concepts of ‘world order’ and ‘global governance’, analysing how familiar institutions first came to hegemony, and later came to be challenged. Methodologically, the author chooses to concentrate primarily on the rhetorical dimension of the rise of BRICS, at the same time analysing the way in which rhetoric brought the organisation to prominence. The book thus presents a case study of the way speech acts morph into tangible, real-world policy.

The narrative begins at the moment of inception of the present world order, with an ascendant West and Russia at the fringe of the new system. The first chapter thus serves to demonstrate the factors that led to the failure to integrate Russia into the Euro-Atlantic community as a junior partner within ‘a larger and more vital West’, an idea often repeated by the late US National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski. Leaving aside the plausibility of such a turn of events, Salzman proceeds to outline the Russian responses to this change in global governance.

Tracing the origins of BRICS to the positioning of BRICS nations against the West, the author shows the economic justification behind this unlikely group of states in the second chapter. This section is primarily concerned with the institutional stage for the birth of BRICS and touches on the question of what constitutes global governance in principle.

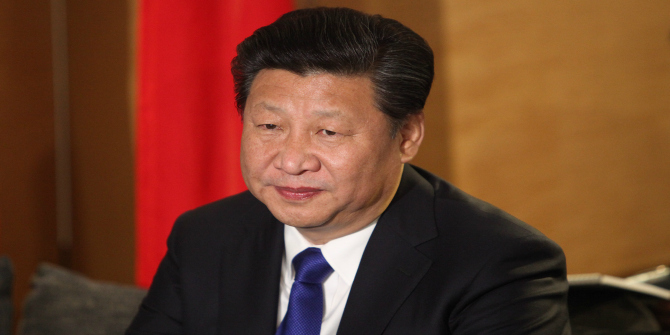

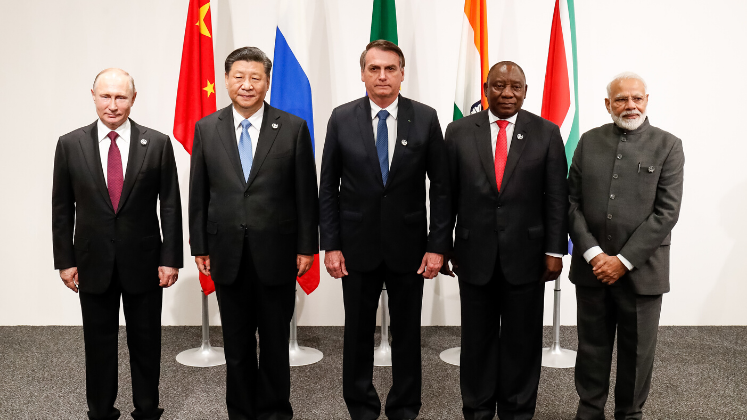

Image Credit: Photo of the BRICS leaders, 2019. Alan Santos/PR (Palácio do Planalto CC BY 2.0)

In the third chapter, the author analyses the ideational foundations of BRICS in the corridors of the Russian foreign ministry and general schools of thought on Russia’s civilisational role in global history. This serves as a brief excursion into the positioning of Russia as an existential ‘other’ to the Western world as it is conceptualised by Russians and by Westerners alike. This primarily concerns the rhetorical shift from Westernism to (a broadly defined) Slavophilia during Vladimir Putin’s first two presidential terms.

The fourth chapter describes Dmitry Medvedev’s short, bizarre and contradictory presidency, marked simultaneously by an initial drive towards rapprochement with the West and the subsequent Russo-Georgian War in August 2008. As such, it drafts the practical impetus that led to the rhetorical ascendance of BRICS as a competitor to the Western order.

In the following chapter, Salzman describes the process of how BRICS came to be seen, at least rhetorically, as a counterbalance to the Western-dominated world in the wake of the annexation of Crimea. The author identifies the rhetorical refuge that BRICS provided to Russian leadership following its ostracisation within Western institutions. Most importantly, Salzman demonstrates how Russia was able to rally support from other BRICS nations in the form of passive resistance to the current system of global governance.

Chapter Six focuses briefly on the role of BRICS in Indian and Chinese foreign policy. Turning away from the narrow interests of Russia, Salzman analyses the teleological drivers behind these countries’ participation in the organisation and shows the conflicting interests behind these participants. This allows the author to analyse the deceleration of the organisational dynamics of the organisation, if not its entropic death.

The conclusion brings the reader back to the starting point: the Euro-Atlantic world order. ‘BRICS is no longer a big story in global governance’ (138), Salzman concludes. On the one hand, she shows the strong desire of the BRICS nations to overturn the status quo and challenge the West’s normative hegemony. On the other hand, she reaffirms the fact that the existing system of global governance has no competition by reminding the reader of the ‘circular firing squad’ nature of cooperation between the nations desiring to overturn it: the difference in interests of BRICS countries provides little potential for cooperation towards a common objective.

Perhaps the most valuable contribution of this study is that it demonstrates that dissatisfaction with the status quo is not endemic to the Russian leadership. The brief prominence of BRICS thus demonstrates that its constitutive nations, while reluctant to openly present a ‘challenge to Western ideational control of global governance’ (140), have ‘transformed the image of the international liberal order’ (144).

At the same time, the narrative of BRICS as a story of how a disgruntled Russia found a way to vent its dissatisfaction does not seem entirely convincing, especially in light of how little prominence other BRICS nations receive in the study. Rather than a conscious attempt to construct a counterbalance to Western institutions, it seems that BRICS owes its inception to a confluence of domestic and international political factors in each nation. As such, in achieving the goal of bringing the reader closer to understanding the rationale and the motivations behind decision-making in Russian foreign policy, the book inadvertently contributes to ‘othering’ Russia as the West’s nemesis by highlighting its civilisational baggage. This is especially evident from Salzman’s stylistic choices: referring to the ‘disruption of global order’, ‘upending the current international system’ (xviii) and the ‘stability of the current system’ (140).

Another concern is whether the author’s decision to focus simply on the rhetorical dimension overinflates the significance that BRICS had in terms of actual policy. Words notwithstanding, the economic and political impact of BRICS has always fallen short of ‘constraining American global hegemony’ (140), especially insofar as influence upon Western economic institutions is concerned. After all, BRICS is an organisation constructed along trade rationales, and draws its gravity from the economic performance of its nations. In other words, it is unclear whether BRICS indeed is more than the sum of its parts.

Setting aside these considerations, Russia, BRICS and the Disruption of Global Order sheds a unique light upon this contested and under-researched coalition. Salzman provides a nuanced understanding of the inner workings of the Russian political apparatus and highlights the transient nature of the system of global governance.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Russia, BRICS and the Disruption of Global Order. Rachel S. Salzman. Georgetown University Press. 2019.

Review translated by Magnus Obermann / 李云龙 (teacher Dr Lijing Shi)

在《俄罗斯、金砖四家和全球秩序的破坏》中,雷切尔·萨尔兹曼(Rachel S. Salzman)提供了一项新的研究,从而试图了解“金砖四国” (巴西、俄罗斯、印度、中国和南非)背后的驱动力。萨尔茨曼试图消除围绕“金砖四国”的误解。Erdem Lamazhapov写道,这本书对这个存在争议且现有研究不足的组织进行了独特的解读,并强调了全球治理体系的短暂性。

在《俄罗斯、金砖四家和全球秩序的破坏》中,雷切尔·萨尔兹曼(Rachel S. Salzman)提供了一项新的研究,从而试图了解“金砖四国” (巴西、俄罗斯、印度、中国和南非)背后的驱动力。萨尔茨曼试图消除围绕“金砖四国”的误解。Erdem Lamazhapov写道,这本书对这个存在争议且现有研究不足的组织进行了独特的解读,并强调了全球治理体系的短暂性。

在浸染于西方国家安全理念的现实主义读者的眼中,俄罗斯的雷切尔·萨尔兹曼所著之“金砖国家和全球秩序的瓦解”中的的故事应该是令人无比恐惧和费解的。这本书讲述了一个企图颠覆稳定世界秩序和反抗后冷战时代制度调整的密谋。这本书希望帮助那些坚持欧洲-大西洋霸权理念的读者了解“金砖四国联盟”(即巴西、俄罗斯、印度、中国和2010年加入的南非)背后的驱动力,并希望消除其他围绕金砖国家的误解。然而事与愿违,这本书很可能更加坚定了许多读者心中对欧洲大西洋全球秩序稳定的信念。

萨尔兹曼提出了“世界秩序”和“全球治理”的建构主义概念,分析了熟悉的制度如何先成为霸权,然后又如何受到挑战。从方法论上讲,作者在分析金砖国家组织发展的理论时,选择了主要关注金砖国家崛起的事实维度。因此,这本书提供了一个案例研究,说明语言行为可以演变成为切实可行的现实政策。本书的叙事开始于当前的世界秩序伊始,西方和俄罗斯都在新体系的边缘上升。因此,第一章说明了导致俄罗斯未能作为一个“更大,更重要的西方国家”的初级伙伴融入欧洲大西洋共同体的因素,这正是已故的美国国家安全顾问兹比格涅夫·布热津斯基经常重复的观点。在没有过多解释这一发展的原因的情况下,萨尔兹曼接着谈到了俄罗斯对全球治理变化的反应。

在第二章中,作者表明在金砖国家的联盟背后有生态经济学的原因。第二章主要关注的是金砖国家成立后的制度影响,并且包含了对真正的全球治理这一问题的探讨。

在第三章中,作者分析了俄罗斯外交史中金砖国家的意识形态基础,以及后者对俄罗斯在全球历史中的角色的立场。这是对俄罗斯和西方 “彼此” 这一理论的简要探讨,俄罗斯人和西方人都持有这种信念。这主要涉及普京在前两届总统任期内从 “西方主义”到“斯拉夫主义”政治立场的转变。

第四章描述了梅德韦杰夫短暂不寻常又充满着矛盾的总统任期。这一任期内的特点是最初与西方的和解进展以及随后在2008年8月发生的俄格战争。因此,梅德韦杰夫的总统任期夯实了金砖国家作为西方秩序的竞争者的论调。

在下一章中,萨尔兹曼描述了金砖国家如何被视为在西方国家主导的国际体系里的一个平衡力量。这发生在克里米亚被吞并之后。作者指出,在俄罗斯领导层被西方机构排斥之后,金砖国家为其提供了言论上的庇护。最重要的是,萨尔茨曼展示了俄罗斯如何以消极抵抗的形式从其他金砖国家那里获得支持,从而形成了目前的全球治理体系。

第六章简要介绍了金砖国家在印度和中国外交政策中的作用。这一章节,作者跳出了对俄罗斯的单一讨论,分析了印度和中国参与金砖国家的动机。萨尔茨曼表明,中印的利益有时是相互矛盾的。这使得作者能够分析该组织的动态减速。

结论将读者带回了本书的论述起点:欧洲-大西洋的世界秩序。“金砖国家不再是全球治理中的一个大事件”(138),萨尔兹曼总结道。一方面,她展示了金砖国家颠覆现状、挑战西方规范性霸权的强烈愿望。另一方面,她重申,现有的全球治理体系暂时还未出现竞争对手。她这样做是为了提醒读者,希望推翻现有体系的国家之间的合作具有 “循环射击队”的性质:金砖国家之间的利益分歧导致不太可能实现共同目标的合作。

这本书最有价值的贡献也许是它表明的观点:对现状的不满并不是俄罗斯领导人所特有的。因此,金砖国家的短暂辉煌表明,其组成国家虽然不愿公开提出“对西方全球治理的意识形态霸权的挑战”(140页),但是“改变了国际自由主义秩序的形象”(144页)。

同时,把关于金砖国家的叙事简化为“是心怀不满的俄罗斯找到的发泄不满的方式”,似乎并不能完全令人信服,尤其是考虑到其他金砖国家在学术研究中的地位并不十分突出。与其说金砖国家有意识地试图构建一种对西方主导国际组织的制衡,不如说金砖国家的成立归功于国内和国际政治因素的集合。因此,该书不但让读者更近一步了解俄罗斯外交政策决策背后的理由和动机,还在无意中促成了俄罗斯作为西方克星的 “另类”的观点。这一点从萨尔茨曼选择的措辞中尤其明显:“全球秩序的破坏”、“颠覆当前的国际体系”(xviii)和 “当前体系的稳定”(140)。

另一个问题是,金砖国家这一响亮的名号是否过度夸大了金砖国家在实际政策中的意义。金砖国家的经济和政治影响始终无法 “制约美国的全球霸权”(140),这一点在对西方经济机构的影响方面尤为明显。毕竟,金砖国家是一个根据贸易考虑而建立的组织,并从其国家的经济表现中获得影响力。换句话说,目前还不清楚金砖国家组织作为整体的贸易总额是否比其各国的总和加起来要多。

总之,《俄罗斯、金砖国家和全球秩序的破坏》一书对存在争议且研究不足的全球大国联盟组织提出了独到的看法。萨尔茨曼对俄罗斯政治机构的内部机制进行了透彻的分析,凸显了全球治理体系的短暂性。