In Creativity in Research: Cultivate Clarity, Be Innovative and Make Progress in your Research Journey, Nicola Ulibarri et al emphasise the invaluable role of creativity for the academic researcher, focusing on the processes and contexts of research in order to help academics foster innovation and imagination in their practices. The book will be useful to early-stage researchers looking to build healthy research habits and for those searching for ways to encourage creative capacities in their students, writes Ignas Kalpokas.

Creativity in Research: Cultivate Clarity, Be Innovative, and Make Progress in your Research Journey. Nicola Ulibarri et al. Cambridge University Press. 2019.

The market for manuals and advice for both early-stage and seasoned researchers is very crowded. Hence, it takes a lot to stand out and offer something original. For the most part, Creativity in Research succeeds in doing this by focusing not on specific techniques and rigid methodological guidance, but on the processes and contexts of research and one’s personal attitude towards it. And yet, perhaps because the subtitle, ‘Cultivate Clarity, Be Innovative, and Make Progress in your Research Journey’, sets the bar of expectations very high, there is the sense of something – perhaps a certain creative flair – missing in the writing itself.

The market for manuals and advice for both early-stage and seasoned researchers is very crowded. Hence, it takes a lot to stand out and offer something original. For the most part, Creativity in Research succeeds in doing this by focusing not on specific techniques and rigid methodological guidance, but on the processes and contexts of research and one’s personal attitude towards it. And yet, perhaps because the subtitle, ‘Cultivate Clarity, Be Innovative, and Make Progress in your Research Journey’, sets the bar of expectations very high, there is the sense of something – perhaps a certain creative flair – missing in the writing itself.

Since the production of new ideas, solutions and contributions is at the heart of academic research, it becomes clear that creativity is the paramount quality of a researcher. And yet, it is also one that is sadly underappreciated, lost underneath the pressures of methods and metrics. Therefore, this book plays an important role in reinstating creativity to its proper place, albeit not always in a particularly inspiring way. Both the style and the contents of the book are rather dry and sterile for a book about creativity, and reading the book necessitates some effort. That lack of flair is, nevertheless, somewhat ameliorated by the authors’ frequent use of real-life examples, which make the advice much easier to relate to – there is no doubt that many readers will recognise their own experiences and personal struggles reflected in the cases provided. A further useful feature is the exercises given at the end of every chapter that allow readers to try out the practices and insights provided by the authors.

Among the important pieces of advice found in the book, some really stand out. While they may sound quite obvious when one gives them more thought, the very fact that we need to be reminded of these is testament to the unhealthy academic environment that most researchers find themselves in. The first such piece of advice is that ‘part of generating novel ideas is absorbing information and then coming up with new associations between things you have assimilated’ (5). The problem, of course, is that being squeezed by the combined load of publishing, teaching and service, academics are unlikely to have the time for such absorption and reflection. Nevertheless, as the authors suggest, shifting the emphasis from content to process might actually enable one to identify the most productive practices and thus squeeze more out of the limited time available.

Likewise, it is stressed that ‘research is both intuitive and analytical’ (10). While in everyday practice researchers are more likely to emphasise the analytical part of the equation, it is intuition premised upon analytical consideration of existing knowledge that provides the necessary innovative step that constitutes one’s contribution to a field of research. In a similar vein, the authors also encourage the development of creative confidence, which is the result of consciously increasing awareness of one’s circumstances and research practices.

The second piece of important advice, and one directly related to the above, is practising a researcher’s version of mindfulness. This includes ignoring superfluous distractions by identifying them and the thought pathways through which they come to presence as well as being aware of which circumstances can or cannot be changed, thereby concentrating on the former. That, in turn, is argued to enable more successful research practices constituted around the triad of conscious intention to approach the problem at hand, give attention to the surrounding processes and cultivate an attitude for accepting things as they are without undue overstretch.

The authors then move to a vindication of emotions that, like intuition above, are also typically seen as the opposite of good research practice. However, the sheer ubiquity of emotions in human judgement means that discarding them means both losing some of the filtering capacity (whereby emotions acts as cues that help filter out environmental ‘noise’) and, perhaps even more importantly, posing a threat to psychological health, because an important part of who we are is constantly being suppressed. Once again, mindfulness becomes the key word – being aware of one’s emotions and the ways in which they both help and hinder research is seen to lead towards a less constrained and more creative research process, while being attentive to one’s psychological needs should reignite joy and inquisitiveness.

A further piece of advice that differentiates this book from most other ‘how to’ manuals about conducting research pertains to a focus on experimentation and iteration. While researchers are typically taught to tackle the problem head-on and treat every version of their manuscript as the final one (not least due to the pressures of time in today’s hectic academia), the authors’ advice here is not to treat any particular version too seriously. Instead of producing the final, (hopefully) high-impact piece, researchers are urged to proceed via a series of incremental steps and experiments – almost like a set of brainstorming sessions. At the very least, this, it is suggested, should relieve the pressure and allow the writing to flow more freely.

Likewise, if the research process is reconceptualised in terms of iteration and experimentation, then the variety of interim ideas is perhaps at its most effective when shared with and discussed among a supportive community of colleagues. Hence, the authors of this book recommend making research a ‘team sport’ – immersing oneself in frameworks and networks, either institutional (research groups, meetings, seminars, etc) or informal and ad hoc (such as chatting to colleagues at conferences). What the authors do not provide, though, is a recipe of how to squeeze all that into the already overstretched schedules of contemporary academics.

Overall, while creativity, innovation and progress feature heavily in the book, the ‘clarity’ bit of the subtitle remains implicit at best. Likewise, while the heavy use of real-life stories facilitates engagement, there are so many of them that these stories may become as distracting as they are engaging. The book leaves this reader with the impression that it has a great idea and mission, as well as quite a lot of good content, but that something has been lost in the writing process. Ultimately, though, it does offer a good proposition for both early-stage researchers looking to build healthy research habits and more senior ones searching for ways to encourage creative capacities in their students. Hence, regardless of its shortcomings, Creativity in Research is worth the effort.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

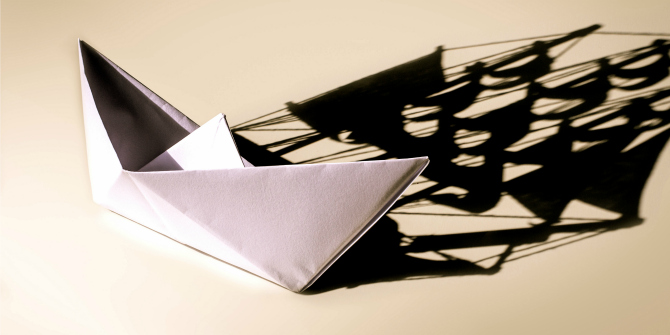

Image Credit: Photo by Rodion Kutsaev on Unsplash.