In The Case for a Job Guarantee, Pavlina R. Tcherneva argues that a job guarantee that provides an employment opportunity to anyone looking for work, regardless of their personal circumstances or the state of the economy, not only makes good economic sense, but is vital for people’s wellbeing. As discussions of a universal job guarantee have never been timelier, The Case for a Job Guarantee is a deeply thought-provoking book and deserves serious consideration, writes Anupama Kumar.

The Case for a Job Guarantee. Pavlina R. Tcherneva. Polity. 2020.

In The Case for a Job Guarantee, Pavlina R. Tcherneva argues that not only does a job guarantee make good economic sense, it is also necessary to people’s wellbeing.

In The Case for a Job Guarantee, Pavlina R. Tcherneva argues that not only does a job guarantee make good economic sense, it is also necessary to people’s wellbeing.

Tcherneva defines a job guarantee as ‘a public policy that provides an employment opportunity on standby to anyone looking for work, no matter their personal circumstances or the state of the economy’. Such jobs provide a living wage and decent working conditions. In her vision, a job guarantee is universal and voluntary – available to all people who wish to make use of it. For Tcherneva, a job guarantee is an end in and of itself, and governments should ensure that jobs are available to their citizens.

The first part of the book argues that a job guarantee makes good economic sense for governments. Tcherneva begins by pointing out that while the US economy may have grown, this has not translated into benefits for ordinary workers. She notes that in 2017, real incomes for the bottom 90 per cent of families were lower than they were twenty years earlier, while those of the top 0.01% had risen by a staggering 60.5%. Unemployment rises dramatically during economic downturns, but recovery is anaemic. For the most part, economic recovery does not create more jobs.

Governments have responded to economic downturns with fiscal stimuli, but these have tended to protect investments rather than jobs. Loan guarantees and bailouts help preserve corporate profits, rather than jobs for citizens. Instead, Tcherneva argues that a job guarantee ought to be treated as a countercyclical measure. A job guarantee would function like a buffer stock programme in agriculture, where the government ‘purchases’ surplus labour at a fixed price. Such a programme would address both inflationary and deflationary pressures from fluctuations in employment. Moreover, by providing steady employment, a job guarantee programme would soften the demand on other countercyclical social protection measures, such as unemployment insurance or food assistance. Finally, unemployment is expensive. According to one estimate, unemployment during the Great Recession that followed the 2008 financial crisis cost the United States $10 billion in output each day.

The more compelling argument, however, is that all persons have the right to decent work. This has been recognised as far back as the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. There ought to be no ‘natural’ level of unemployment, any more than there is a natural level of starvation or illiteracy. Tcherneva reasons that the inflationary effects of unemployment are vastly overstated, and that instead there are real costs to joblessness for individuals and communities. Unemployed individuals have shorter lives and more chronic illnesses than those who are not unemployed. These have effects not only for individuals, but on families dependent on them. Further, unemployment is contagious – mass layoffs in one area lead to chronic unemployment, which spreads to surrounding communities.

The author argues that the responsibility to hire workers cannot lie solely with the private sector. The private sector is in the business of making profits and not in providing jobs to those most in need of them. Nor are labour laws enough to ensure that workers receive a living wage and decent working conditions. At any time, there are more jobseekers than employers. In the absence of a job guarantee, workers will lack the ability to refuse unsafe, poorly paying jobs, as employers will always have the upper hand.

A job guarantee programme that assesses the needs of communities locally, and provides adults with employment within that community, can provide a solution to this. A bottom-up approach, which encourages people to participate in job creation, can work better than a top-down, bailout-led model. Moreover, a locally administered job programme can provide valuable services to the community, including preserving the local environment.

In proposing this theory of job guarantees, Tcherneva argues that most jobs today are not in manufacturing, but in services such as care work or education. These are jobs that cannot easily be replaced by automation – there is no substitute for a human touch in hospice care. In Tcherneva’s vision, the types of work a job guarantee would involve relate to services at the local level, in building community goods and public services and enabling environmental conservation (a Green New Deal). People making use of this programme would also acquire skills that would enable them to take up employment outside the job guarantee programme, thereby contributing to the economy. The job guarantee would, however, continue to hire people who do not move to private sector employment. The services provided by these jobs would also lead to a net benefit for the community around them.

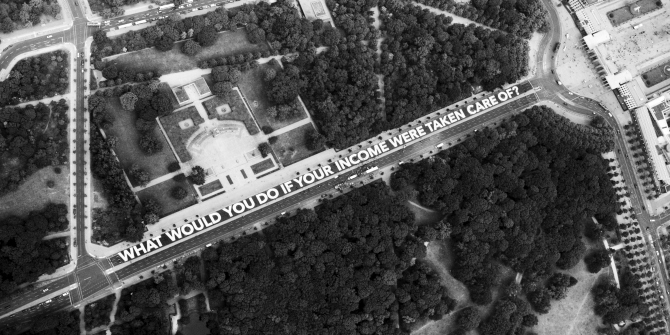

While the book makes a convincing case, a deeper analysis of some questions would have been welcome. First, why is a job guarantee a better proposal than a universal basic income? While not explicitly stated in the book, the reasons for this seem to be that job guarantee programmes generate productive assets, reduce the burden of unemployment (psychological and otherwise) and create a sense of dignity for workers receiving a living wage for an honest day’s work. Would a UBI be able to perform some of these functions better, especially for those too ill or too old to work?

Second, is a short-term guaranteed job at living wage – but no more – enough to provide the skills to move to employment in the private sector? As Tcherneva notes, the private sector is not in the business of hiring people who need jobs, but in making profits. The types of services provided by the private sector reflect this. Today’s gig economy players such as Uber or Deliveroo essentially enable private contracts between individuals, and do not create the kinds of public goods a job guarantee programme might. Will private players now shift to sectors for which the skills acquired in a job guarantee programme will be useful? If not, will the public sector need to continue to provide jobs for workers? In Tcherneva’s argument, this is not a problem – providing jobs is a valid goal in and of itself.

Finally, Tcherneva’s analysis is specific to the United States. It would be interesting to examine the differences between job guarantees in the Global North, where there are well-established social security programmes, and those in the Global South. Tcherneva cites Plan Jefes in Argentina and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) in India as instances of ‘successful’ job guarantees, but does not elaborate on how these are different from the circumstances in the United States.

In sum, discussions on a universal job guarantee have never been timelier. The Case for a Job Guarantee is a deeply thought-provoking book and deserves serious consideration.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Banner Image Credit: (Andrew_Writer CC BY 2.0).

Feature Image Credit: Jobs Help Wanted.Taken for post on Innov8Social on job creation by social entrepreneurs (Innov8Social CC by 2.0).

2 Comments