In The Licit Life of Capitalism: US Oil in Equatorial Guinea, economic anthropologist Hannah Appel closely examines the operations of US oil companies in Equatorial Guinea, not only revealing the sheer extent and dimensions of corporate power in remaking the world, but also illuminating the ongoing project of capitalism itself. This is a revelatory study in its theoretical contributions to the anthropology of capitalism, with a critical recentring of attention on the role of industry in shaping the politics and economics of resource extraction, writes Wen Zhou.

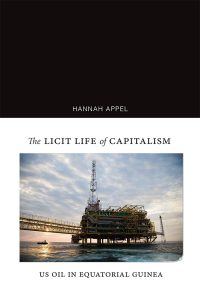

The Licit Life of Capitalism: US Oil in Equatorial Guinea. Hannah Appel. Duke University Press. 2019.

Equatorial Guinea, a small Central African country that faces the Atlantic from the Gulf of Guinea, describes itself in government reports as offering ‘the most flexible fiscal environment in the world’. Of course, there’s stiff competition for this distinction: Caribbean island tax havens, the free market citadel of Singapore and a spate of newly designated special economic zones across the Global South similarly beckon investors with promises of unleashed returns in the absence of regulation. But the former Spanish colony of Equatorial Guinea presents as a particularly spectacular site of state-sponsored capital accumulation, where Exxon’s discovery of offshore hydrocarbon deposits in the 1990s (bearing a production capacity equal to three times that of the company’s then-worldwide production) has led to a singular alignment of US oil companies with the government of President Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, blurring the lines between state and corporate sovereignty over territory, resources and the environment.

Equatorial Guinea, a small Central African country that faces the Atlantic from the Gulf of Guinea, describes itself in government reports as offering ‘the most flexible fiscal environment in the world’. Of course, there’s stiff competition for this distinction: Caribbean island tax havens, the free market citadel of Singapore and a spate of newly designated special economic zones across the Global South similarly beckon investors with promises of unleashed returns in the absence of regulation. But the former Spanish colony of Equatorial Guinea presents as a particularly spectacular site of state-sponsored capital accumulation, where Exxon’s discovery of offshore hydrocarbon deposits in the 1990s (bearing a production capacity equal to three times that of the company’s then-worldwide production) has led to a singular alignment of US oil companies with the government of President Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, blurring the lines between state and corporate sovereignty over territory, resources and the environment.

In her book, The Licit Life of Capitalism, economic anthropologist Hannah Appel closely examines the operations of US oil companies in Equatorial Guinea, not only to discover the sheer extent and dimensions of corporate power in remaking the world to suit its purposes, but also to illuminate the project of capitalism itself. Indeed, one of Appel’s key interventions is for us to reconsider capitalism as an ongoing project, one that requires constant work by corporate actors to create the effects of ‘standardization, decontextualization, and distancing’ otherwise considered inherent to capitalism.

Based on fourteen months of ethnographic fieldwork conducted in and around the capital city of Malabo, engaging with company staff and their spouses on offshore oil rigs and residential compounds, as well as with government officials and those active in opposition politics through a fortuitous position on Equatorial Guinea’s Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, Appel argues that oil companies play a pivotal role in the politics and economics of Equatorial Guinea. While this is a seemingly banal observation, it has nonetheless long been occluded by the industry’s successful efforts to ‘offshore’ itself from its immediate contexts and consequences. Of course, Appel’s broader theoretical contribution is to highlight the role of industry in shaping the politics and economics of oil at large, where oil and capitalism have become nearly synonymous and interchangeable objects.

Image Credit: Cropped image of ‘SEA BEAR , H-542 , Alba field B3 , RT SPIRIT & RT MAGIC’ by kees torn licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Image Credit: Cropped image of ‘SEA BEAR , H-542 , Alba field B3 , RT SPIRIT & RT MAGIC’ by kees torn licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

In richly evidenced chapters, Appel traces the oil industry’s active production of the ‘licit life of capitalism’, or its legally negotiated and legally defensible project of capitalism, to the enacted ‘forms and processes’ of offshore infrastructures and corporate enclaves, contracts and subcontracts and – in a rather different modality – circulating economic theory and liberal ideals of transparency. Offshore oil rigs and inland housing compounds (what Appel terms ‘the domestic offshore’) are thus the literal manifestations of ‘distancing’ that allow for both unfettered operational freedoms and separation from the friction of local contexts.

On the other hand, the use of subcontracts allows corporations to legally displace responsibility for practices and activities undertaken on their behalf, while the use of contracts unites companies and states in legal fiction as co-equal signatories, simultaneously legitimating a fragmented political regime while shielding the industry from the evident incapacities of this same government. In this manner, Appel demonstrates the real achievements of ‘the industry’s striving for capitalism in its own image’ as it seeks operational coherency despite the messiness of on-the-ground realities. Indeed, the successes of these corporate strategies result in the transubstantiation of capitalism, from attempted project to living structures and real effects.

While they are not the products of corporate endeavour, resource curse theory and ideals of transparency further contribute to an environment in which the oil industry is able to distance itself from its role in producing the very conditions of inequality it claims as pre-existing grounds. Resource curse theory attributes the real development failures of resource-rich countries to state neglect of alternative economic sectors and mismanagement of their newfound wealth. As a highly credible economic theory, its circulation from academic journals to corporate offices provides cover for those company practices that divert oil profits away from Equatorial Guinea and exacerbate economic inequalities, including the negotiation of favourable profit-sharing contracts with the state, the differential treatment of employees by nationality through the use of subcontracted ‘body shops’ and the avoidance of tax liabilities through legal self-dispersion into an ‘archipelagic corporate form’. At the same time, the theory’s legitimacy also permits corporate actors to reiterate longstanding tropes of the inherent pathologies of African states and economies. Finally, external efforts to reform the industry’s excesses are further premised on liberal ideals of a state and civil society that simply do not exist in Equatorial Guinea; the close interlacing of state and corporate authority in the country further dashes expectations that the introduction of transparency alone would precipitate effective checks to corporate power.

Despite Appel’s finely grained demonstration of how the project of oil capitalism is operationalised through these disparate forms and processes, her analysis often occludes the agency of those human actors whose decisions coalesce in the construction of this unwieldy and powerful assemblage, and whose lives are regulated and transformed by its operation. Instead, depictions of individual interlocutors appear almost entirely in service of the theoretical import of their structural positioning, whether as agents or subjects of capitalist ends. For instance, in describing the roles of the expatriate wives of (the nearly uniformly white male) company executives, a diverse group of women are consigned to the rarefication of ‘heteronormative white domesticity’ behind the ‘walled boundaries of conjugal conscription’, thus serving for Appel to reproduce the norms of a gendered and racialised capitalism.

In like manner, the setting of Equatorial Guinea is often reduced to one of ‘imperial debris’, a term Appel borrows from Ann Laura Stoler (2008) to describe how the historical legacies of colonial dispossession and post-colonial authoritarianism have created an ideal environment for the arrival of oil capitalism. While Appel rightly stresses the importance of history in shaping those structural conditions – the near-absence of legal instruments, the high dependency on external revenue sources – that have allowed US oil companies overwhelming leverage in deciding the terms of their tenancy, the collapsing of wide-ranging histories under the label of ‘imperial debris’ effaces alternative understandings of the living, changing specificity of the country itself.

Of course, these may seem like minor quibbles in the face of Appel’s primary objective to demonstrate the ‘persistence and performativity of the offshore’ (albeit alongside the ‘sociality’ of the same), or even unfair in light of Appel’s early disclaimer that hers is emphatically not a conventional ethnography of Equatorial Guinea. But what happens when ethnographic liveliness is lost, and when the cacophonous voices of places and peoples are corralled into theoretical unity for the seemingly inevitable advance of capitalism in and through their sites and bodies? If people are the unwitting instruments of capitalist expansion, and history produces the all-too-ready conditions for capitalist domination, then capitalism comes to appear far less as contingent project than as teleological end.

Nonetheless, Appel’s study of US oil companies in Equatorial Guinea is revelatory for its theoretical contributions to the anthropology of capitalism (beyond the rather more niche anthropology of oil), with a critical recentring of attention on the role of industry in shaping the politics and economics of resource extraction. With enviable access to the internal operations of these transnational corporations, Appel provides key insights into the assumptions and worldmaking strategies of what has long been an ethnographic black box. At the same time, the particular conjuncture of North American corporations in an African postcolony leads Appel to underscore the racialised and gendered dimensions of capitalist expansion and reproduction, as features both particular to her ethnographic subject and universal to the processes of capitalism at large. It is this productive tension, between the nature of specific capitalist projects and the global movement of which they are both expression and experimentation, that would serve as a stimulating ground for further inquiry into the means and modes of their co-constitution.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Cropped image of Alba 3 compression platform being transported to Equatorial Guinea, 2015 (kees torn CC BY SA 2.0).