In Michael Young, Social Science and the British Left, 1945-1970, Lise Butler explores the relationship between social science and public policy in left-wing politics through the figure of social scientist and policymaker Michael Young, one of the influential and innovative figures of post-war Britain. Carefully tracing Young’s trajectory between 1945 and 1970 to demonstrate the utterly coherent intellectual project underlying Young’s work, this excellent book positions Young’s influence, achievements and limitations within a particular historical moment that was to end with the economic turmoil and political crises of the early 1970s, writes Mike Savage.

Michael Young, Social Science and the British Left, 1945-1970. Lise Butler. Oxford University Press. 2020.

Michael Young was surely one of the most enigmatic ‘movers and shaker’ in post-war Britain. On the one hand, his role as a ‘social visionary and innovator’ (to use the term which adorns his own headstone) was surely without parallel. Writing the successful 1945 Labour Party manifesto; leading the Institute of Community Studies which was to pioneer new research not only on community, but also on poverty and ageing; the Consumers’ Association; the Open University; the Social Science Research Council; the journal New Society; popularising the ‘meritocracy’ concept; the University of the Third Age. And so this dizzying list might be expanded: I hadn’t realised until I read Lise Butler’s revealing book that he also played a significant role in forming the British Sociological Association in 1951, for instance. Leading any one of these initiatives would be a career-defining achievement: to be a key figure in all of them is astonishing.

Michael Young was surely one of the most enigmatic ‘movers and shaker’ in post-war Britain. On the one hand, his role as a ‘social visionary and innovator’ (to use the term which adorns his own headstone) was surely without parallel. Writing the successful 1945 Labour Party manifesto; leading the Institute of Community Studies which was to pioneer new research not only on community, but also on poverty and ageing; the Consumers’ Association; the Open University; the Social Science Research Council; the journal New Society; popularising the ‘meritocracy’ concept; the University of the Third Age. And so this dizzying list might be expanded: I hadn’t realised until I read Lise Butler’s revealing book that he also played a significant role in forming the British Sociological Association in 1951, for instance. Leading any one of these initiatives would be a career-defining achievement: to be a key figure in all of them is astonishing.

Yet in another respect, Young’s life was marked by systematic and repetitive failure. Butler discusses how the Labour Party was not persuaded by his interest in families and their political emphasis on production and employment issues was undiminished: his influence on Labour policy after 1945 was minimal. He failed to become an established academic: his dream of becoming the first professor of sociology at Cambridge did not come to pass. Community studies fell into disrepute as a major intellectual field after the later 1960s. Even though his pathbreaking Family and Community in East London had a mass readership, it is surely one of the most criticised studies of all time. This criticism began with its own preface, perhaps one of the sniffiest ever written (by Richard Titmuss, his own PhD supervisor, no less), continuing to Jennifer Platt in 1971, and more recently historians such as Jon Lawrence (as well as Butler herself) who all dispute his evocation of matricentred communal life in Bethnal Green. He is not now held in renown as a hallowed progressive intellectual in the George Orwell or Richard Hoggart mould.

Butler’s excellent book, Michael Young, Social Science and the British Left, 1945-1970, makes sense of these fascinating dissonances by drawing on the perspective of Cambridge School intellectual history, which emphasises that ideas make sense in their context and need to be rescued from their later canonisations and critiques. This is especially important in Young’s case because disciplinary divisions in the social sciences have become so entrenched that they colour how pioneers are viewed retrospectively. She thus draws out the astonishing disciplinary range of Young’s intellectual formation: a degree in economics; trained in law; doctorate in social administration, championing anthropological methods; closely acquainted with psychology; a one-time lecturer in sociology.

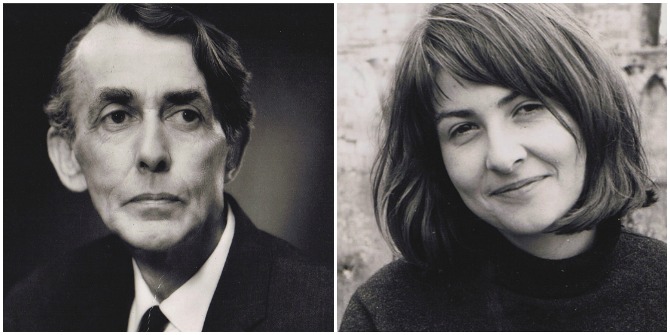

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Lord Young’ by tpholland licensed under CC BY 2.0.

From the perspective of today’s disciplinary norms, it is easy to understand how Young might be viewed as jack of all trades, master of none. But here Butler deftly brings out the utterly coherent intellectual project underlying Young’s work, tracing his trajectory carefully from 1945 to the later 1960s. Although Butler does not make this explicit, this journey can be seen as typical of many on the ascendant political left – TH Marshall, GDH and Margaret Cole, Leonard Woolf. Young’s underlying pre-occupation was how the civilising gentlemanly mission associated with British imperial power could be domesticated into a project of national state building organised around an expanded form of citizenship. Butler shows how ideas that Young elaborated in the later 1940s, out of discussions about the ‘psychological and sociological problems of modern socialism’, undergirded his subsequent career and render his apparent changes of direction as entirely consistent and coherent. Throughout these years he was preoccupied with the vitality of everyday social relationships embedded in the ‘social field’ of family and community and sought ways to renew small-scale sociality in the face of large impersonal forces.

Butler is outstanding in her earlier chapters, where she shows how what might appear as abrupt changes of course in Young’s career actually mark a consistent development from the 1945 discussions inspired by encounters with psychologist John Bowlby (Chapter One). Subsequent chapters discuss his work in Political and Economic Planning (Chapter Two), around ‘family policy and women’ (Chapter Three), the Institute of Community Studies (Chapter Four), the Consumers’ Association (Chapter Five) and the Social Science Research Council (Chapter Six). All these ‘modernising’ initiatives can be seen to rest on this romantic vision which had been put in place from his youth. It is only in the last of these chapters that Butler’s compelling narrative falters slightly, as she seems equivocal about the significance of the SSRC and Young’s role in it, and veers off into a slightly disconnected discussion of its attempts at social forecasting.

Butler succeeds brilliantly at placing Young in his context to draw out both his effectiveness yet also the limits of his work. Young championed research on families and women in the short window of time before feminists exposed the dangers of male-centred perspectives. He helped canonise ‘classic’ white working-class communities at a time when there was no powerful constituency of scholars working on race and ethnicity to expose their racist aspects (Butler notes how his role in the New East End re-study published after his death in 2002 was to fall foul of this critique). And, although Butler emphasises Young’s influence within the political left, she also provides ample evidence of his ability to engage with conservative intellectuals at a time when a cross-party consensus about social welfare was considerable.

In short, by bringing out the consistency of Young’s work and his capacity to achieve such striking results in a mere twenty-year period, Butler also underscores that he could only succeed in this peculiar historical moment which was to end with the economic turmoil and political crises of the early 1970s. It is not incidental that his influence faded in the last 30 years of his life. There is no future Michael Young waiting in the wings to ride to the rescue of social innovation and social science in the 21st century, I will wager.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Banner Image Credit: Still of ‘Michael Young Building 360’ by CobaltWildlife licensed under CC BY 2.0.