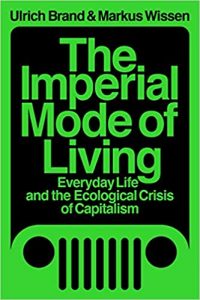

In The Imperial Mode of Living: Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism, Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen show how an ‘imperial mode of living’ underpins everyday life in the Global North, which relies upon the exploitation of people and places across the world and can only be sustained by intensifying economic and ecological crises. This book not only offers a novel grasp of the links between everyday life and global inequalities, but it also takes a stand for the necessity of politics from below, writes Stefan Schoppengerd.

A version of this review was originally published by the paper express – Zeitung für sozialistische Betriebs- und Gewerkschaftsarbeit, No. 8/2017, page 16, and is reproduced here with permission.

The Imperial Mode of Living: Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism. Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen (trans. by Zachary King). Verso. 2021.

The Imperial Mode of Living seems to be a book for these times. After the publication of the German version of the book, many reviews have been published, including in the daily papers, and radio shows have featured it. For a book with a decidedly critical approach to capitalism, this is quite remarkable.

The Imperial Mode of Living seems to be a book for these times. After the publication of the German version of the book, many reviews have been published, including in the daily papers, and radio shows have featured it. For a book with a decidedly critical approach to capitalism, this is quite remarkable.

The Imperial Mode of Living apparently touches a nerve by tapping into the widespread discomfort with consumer culture: the fact that humanity is in the process of destroying its own foundations of life can by now be considered common knowledge. So as to live with one’s own participation in this process, however, that knowledge must constantly be suppressed during everyday life. Even where there is sufficient money, time and goodwill to try ‘sustainable consumption’, at a minimum the notion is spreading that such consumption serves more conscience hygiene than actually offering a contribution to solving the ecological problems of this world. We are all in the midst of it and a comfortable way out is not on the horizon – that’s approximately the problem Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen tackle in The Imperial Mode of Living.

That it is ‘humanity’ which destroys the planet, that ‘all of us’ are in the midst of it, however, are phrases which can no longer be written easily after reading this book. The authors’ interest lies primarily in international imbalances and the impossibility in principle that the Global North’s mode of living can be extended to all human beings – not only because it excessively claims natural resources, but also because it requires, as the authors show convincingly, the exploitation and exclusion of people elsewhere. Exclusivity is its founding principle; those excluded are nonetheless ruled by the ‘inside’ – after all, the streams of cheap raw materials and manufactured goods require their labour. This relationship of exploitation and exclusion characterises the ‘imperial’ in the criticised mode of living.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

The process of capital accumulation is dependent on prerequisites it cannot provide by itself. Here the authors are in agreement with earlier theories of imperialism where ‘elsewhere’ was mainly thought of as territories that must be conquered and ruled, and with the idea of an ‘inner land grab’: that is, the assessment that social circumstances are increasingly penetrated by the principle of utilisation of value. Global acts of land grabbing illustrate both the misery of capitalism-compliant environmental policy and the interlocking of dispossession and market processes:

When, for example, a piece of land extensively used by small farmers in the global South is declared ‘‘uncultivated land’’ and the established right of customary use is transformed into a formalized legal system that marginalizes the previous users, then this is an act of dispossession. If the same piece of land is sold to an energy company from the global North, which sets up a eucalyptus plantation for the sake of CO2 absorption, thereby fulfilling a part of its duties to reduce CO2 emissions, then it is integrated into the international emissions trading system (47-48).

The idea of separating interior and elsewhere, which the authors use throughout, is in principle plausible. Nonetheless, the reasoning here remains rather sketchy: can the borders between inside and elsewhere really still be specified in terms of geography, or do all countries of the world have a ruling class that profits from the imperial world order and thus is a member of the exclusive ‘interior’? How do the various functions for stabilising the imperial mode of production and living elsewhere relate to each other – supplying raw materials and labour, absorbing excessive capital and excessive products, ‘frontiers’ of expansionist desires? The book only supplies approximations regarding the answers to such questions.

However, in using the term ‘mode of living’, the authors succeed in grasping how global power relations are embedded in the everyday actions of people in the Global North without raising moral accusations. This ‘mode of living’ is explicitly more broadly formulated than ‘lifestyle’, which, as a part of modern sociological research into inequalities, is usually understood as a collection of free decisions about consumption. If production and consumption activities in the Global North are created in such a way that the region excessively uses up resources, creates waste and pollutants, then it is not really possible for the individual to remove themselves from being a beneficiary and participant in this process – where does the coal originate from by which the steel was manufactured, which forms the material for the infrastructure of the environmentally friendly public transit system that in urban areas allows people to decide against driving cars?

The imperial mode of living has the hallmarks of compulsion, but at the same time it is enabling, creating conveniences and expanding scopes of action. While it can be sustained only by the price of intensifying economic and ecological crises, it contributes to the stabilisation of the societies of the Global North, including their injustices, and remains attractive for those excluded, whose hopes are not necessarily pinned on overcoming the imperial conditions, but on participating in its exclusive privileges.

The authors leave no doubt that they consider a very fundamental change of social conditions necessary and desirable. In the first chapter, they point out that the ‘whether’ of change isn’t in question, only the ‘how’ – standing still is death; constant change is part of the essence of capitalism. However, transformation can follow different types of logic, and Brand and Wissen advocate for a political logic that emphasises conflicts of interest and goes on the offensive to settle them. Here they are guided by the idea of ‘radical reformism’: such reformism – different from traditional social democracy and state socialism – does not see the state as the most important entity shaping society. On this basis, they also criticise the dominant aspects of an ecological discourse, which, while appealing for change, doesn’t want to get involved in open conflict with the powerful. Thus, The Imperial Mode of Living not only offers a novel grasp of the links of everyday life to crises and inequalities on a global scale, but it also takes a stand for the necessity of politics from below.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.