We speak to Dr Jacob Breslow about his new book Ambivalent Childhoods: Speculative Futures and the Psychic Life of the Child, an interdisciplinary study which explores how childhood is mobilised within and against contemporary US social justice movements, including Black Lives Matter, transfeminism, queer youth activism and antideportation movements.

LSE Department of Gender Studies is hosting the online public event ‘Imagining Childhoods Otherwise’ to celebrate the publication of Ambivalent Childhoods on Wednesday 13 October 2021. Find out more about how to attend.

Q&A with Dr Jacob Breslow on Ambivalent Childhoods: Speculative Futures and the Psychic Life of the Child. University of Minnesota Press. 2021.

Q: Your book asks the powerful question: who gets to be a child? Why is it so vital that we explore who or what gets excluded and included in the idea of childhood?

Q: Your book asks the powerful question: who gets to be a child? Why is it so vital that we explore who or what gets excluded and included in the idea of childhood?

This question of who gets to be a child has been asked within the scholarship for decades, but it remains important because how it gets answered has extraordinary material consequences — and not just for children. We often assume that childhood is a biological category or a time of innocence and protection, and that the exclusion of marginalised individuals and communities from it is central to their dehumanisation. Yet childhood is a deeply ambivalent concept and is not always a site of care and protection. It is also a structure of dependency, dismissal, exploitation and violence.

We might alternatively ask: ‘what does it mean to “get” to be a child, when childhood means you’re understood as inferior?’ Or: ‘who “gets” to be an adult?’ Or: ‘who is framed as a child (or as childlike) despite not “being” a child?’ Here we could point to the ‘adultification’ of black children in the criminal (in)justice system; the infantilisation of women (Shulamith Firestone’s ‘Down with Childhood’ is great on this); or the logics of ‘innocence’ and ‘protectionism’ that get mobilised against young trans people seeking healthcare. What’s interesting is that despite the clear ambivalence of the category of childhood, many social movements, scholars and communities still invest (sometimes strategically) in childhood as a straightforwardly ‘good’ or useful concept. Ambivalent Childhoods is less interested in making a case for a more inclusive or exclusive definition of childhood. I interrogate what is at stake in the wish for childhood. What does childhood do and for whom? In what moments? What else could childhood do? And what would it take to allow it to do so?

Q: What role does ambivalence play in your book?

Ambivalence plays two main roles. First, I argue that it is important for us to understand childhood as ambivalent in the ways I describe above. Second, I want us to think further about what it is that ambivalence does, and I want us to understand it as productive. We often think of ambivalence as either (incorrectly) indifference or, more closely, the experience of being stuck between two equally intense affects. People tend to liken it to a ‘paradox’, where two contradictory things are true at once. Often, this understanding becomes the end of the inquiry, as if the discovery of something having multiple, conflicting meanings is evidence that there isn’t much to be done about it.

But ambivalence, I argue, is not a stationary or ‘stuck’ state of being; it is one of movement and change. Acknowledging the ambivalence of childhood innocence — its capacity to protect some people from harm, on the one hand, yet its propensity to render black, queer, trans people as threats to children, and thus as deserving harm, on the other — begins the work of unsettling our investment in the concept. Coming into an awareness of the inherent ambivalence of childhood, and one’s own ambivalent relationships to it, can open us up to new ways of imagining childhood otherwise. Taking on this project is urgent, because refusing to grapple with childhood’s psychic and political ambivalence enables it to remain complicit in the persistence and force of racism, transmisogyny, heteronormativity and the violences of the border.

Q: Each of your chapters is structured around a site of contestation and a corresponding psychoanalytic concept. Why is psychoanalysis so generative for thinking about childhood? Did you experience any ambivalence working with it?

Each chapter explores childhood through a different moment in which it becomes a stand-in for contestations over race, gender, sexuality and national belonging. It also argues that the psychoanalytic concepts of disavowal, projection, desire and dream-work can help us critically engage with these instances of struggle. Psychoanalysis is tricky to work with, because its concepts are extraordinarily complex and it has a longstanding history of misogynistic, racist, colonial and homophobic knowledge production that is contested by critical and intersectional feminist scholars. But there are also scholars — Judith Butler, David Eng, Gail Lewis, Jacqueline Rose, Gayle Salamon and Antonio Viego, among many others—who take up psychoanalytic approaches to try and get at the psychic investments we have in structures and ways of being that cause us harm.

In Ambivalent Childhoods, I mainly engage with a depathologised Freudian psychoanalytic approach, and I interrogate what I call the ‘psychic life of the child’. Psychoanalysis is really generative for thinking about childhood in particular, because the child — as both subject and figure — has been central to the formation of psychoanalysis. In psychoanalysis, childhood is never simply a moment in one’s past: it is something that continues on with you throughout all moments of life, and it informs how you experience loss, love, fear, abandonment, trauma, etc. Because our own childhood (as a stage of life and a lived power relation) is so integral to who we imagine we are, it often becomes the filter through which we experience the moments that childhood (as an idea and as a cultural signifier) is mobilised as a stand-in for race, gender, sexuality and national belonging. It is really important that scholars of childhood and social movements attend to the psychic life of the child, as this enables us to more fully understand what’s at stake in the uneven and ambivalent justifications of who or what is included or excluded from childhood.

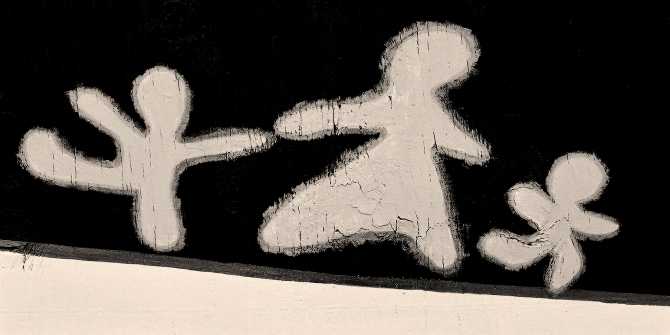

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Photos from the Million Hoodies Union Square protest against Trayvon Martin’s shooting death in Sanford, Florida’ by David Shankbone licensed under CC BY 3.0

Q: In Chapter One you discuss the killing of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin. What did media representations of Trayvon reveal about how antiblackness shapes who is allowed access to the ‘innocence’ of childhood and who can occupy the position of ‘the child’ in the first place?

It’s important to acknowledge the wealth of scholarship on what William David Hart insightfully names the ‘execution’ of Trayvon Martin. My work seeks to join this conversation by reflecting on how antiblackness and childhood give meaning to one another. I examine the visual and discursive landscape that arose in the aftermath of Trayvon’s murder. I argue that racially bifurcated notions of childhood (and adolescence) were central to the national debate about his death and, by proxy, black citizenship, black belonging and black critique.

Following his murder, Trayvon was incessantly represented as a ‘troubled teen’ by the media in ways that were racist (and often beggared belief). This disavowal of his location in childhood was a primary strategy by which the Zimmerman campaign sought to render Trayvon culpable for his own death. At the same time, many of those advocating for justice in Trayvon’s name did so through the insistence that he was an innocent child — made so starkly clear in the recognition that on the night he was murdered he was simply out buying candy. Assessing these two seemingly oppositional articulations of childhood, I argue that they share a similar logic: both assert that childhood was the defining factor of whether or not Trayvon deserved to live.

While I share the insistence that the Martin family receive justice, my argument asks that we find alternative ways of advocating for dignity and justice outside of the narrow (and historically antiblack) logics of childhood. Learning from the Black Lives Matter movement, I argue that advocating for children like Trayvon must not be done in ways that are complicit with structures of criminalisation and antiblackness. Sadly, it is extraordinarily urgent that we grapple with the work that childhood does in these moments because Trayvon was not the first and will likely not be the last black child whose post-mortem representation in the media is so laden with antiblackness that their childhood is vociferously disavowed. We need to ask ourselves: is ‘childhood’ really the grounds upon which we want to argue that someone deserves dignity, justice and life? What strategic ground are we conceding in that moment and what violent logics are we perpetuating? What other modes of representation can be used to reconfigure the ways in which we value life and insist on justice?

Q: In Chapter Two, you examine the transmisogyny directed at a young trans girl, Coy, in the US. How does the ambivalence of childhood affect advocacy for trans children and the capacity to forge a transfeminist politics?

In 2012, Coy, then a six-year-old, was told that she would no longer be able to use the girls’ restrooms at her school because she was trans and her presence might make the other girls uncomfortable. Her parents removed her from school and filed a discrimination complaint, arguing that her exclusion was an act of transphobia (which it was). In the court case, Coy’s school district kept describing the alleged threat of her presence in the girls’ restroom as equivalent to, or foreshadowing, an adolescent hyper-masculine man (with ‘mature sex organs’) entering that space and threatening the other girls. This is a repeated tactic (and fantasy, as Jules Gill-Peterson, Grace Lavery and Marquis Bey argue) of anti-trans organising: insinuating that trans inclusion is a foil for, or an enabler of, adult men’s physical and sexual access to young (white) girls. This narrative is pervasive, extraordinarily disingenuous and refuses to acknowledge that countering transmisogyny is beneficial to all women, including non-trans women.

I think about what it meant that this transphobic narrative relied on equating a six-year-old trans girl with an adult man — what does this fantasy mean for how we understand trans childhood, and the gendering of childhoods more generally? Despite the fact that children are hyper-gendered in ways that are astoundingly destructive, children are also understood as either androgynous or as too young to be aware of gender. This positioning of children as ‘prior’ to gender means that when trans children assert their own understandings of their gender, they are seen as being ‘precocious’ or as already being aged out of childhood. The school district’s positing of Coy as already being an adult was in some ways aligned with how trans children are constructed in media narratives and (some) accounts of trans childhoods from trans people themselves. For those of us advocating for children like Coy — seeking to articulate a transfeminist politics that centres trans children — it’s really important to critically engage with the ambivalences of childhood and gender that circulate in narratives of trans childhoods. Unfortunately, doing this work is becoming increasingly urgent, particularly here in the UK, as anti-trans advocates (organising under the label ‘gender critical’) are rapidly chipping away at the already meagre services available for trans children.

Q: In Chapter Three, you explore the role that the ‘queer child’ has played in queer theory in recent years. In what ways has the queer child become so central in queer theory? How does your study enter into dialogue with these discussions?

This chapter is the most ‘inward’ looking, because it is where I explicitly locate myself within the discourses being critiqued and its gaze is attuned more to scholarship than to social movements or media narratives. This is partly because the ‘queer child’ is still a profoundly taboo subject, even in places where queerness has been co-opted by the state, the police and the market as Pride™. One clear example of this cultural uneasiness around queer children is how loving and supportive mother of the queer youth activist, model and drag kid Desmond is Amazing has been routinely reported to Child Protective Services, under (completely false) allegations that she is subjecting her queer child to sex work. In this political landscape, where support of a queer child renders you a threat to children, it is only really within theory that there is some (still precarious) space to think about the queerness of childhood, and the queer child.

Within queer theory, the ‘queer child’ has been a remarkably productive arena of thought and critique from scholars like Kathryn Bond-Stockton, Lee Edelman, Jack Halberstam, Mary Zaborskis, Gabrielle Owen and Hannah Dyer. I enter into conversation with these scholars (and others) by proposing a ‘queer child’ of my own: Aviva, the thirteen-year-old main character from Todd Solondz’s film Palindromes (2004). I explore the ways that Aviva’s unwavering desire for a child of her own productively troubles (and mirrors) queer theory’s own desires for a ’queer child’. My focus is on how the ‘queer child’ emerged in queer theory, what psychic investments (in queerness and in childhood) shape its contours and what the gaps are — in relationship to motherhood, feminist theory and reproduction — in theorising it.

Image Credit: ‘Protesters hold various signs and banners at a DACA rally in San Francisco’ by Pax Ahimsa Gethen licensed under CC BY SA 4.0

Q: What do the experiences of the DREAMers movement, discussed in Chapter Four, reveal about how the construction of childhood also affects the positioning of adults?

It was really important to stress that the idea of childhood impacts all of us, whether or not we still think of ourselves as children. The final chapter interrogates this dynamic between adult and child by looking to the activist strategies deployed by DREAMers and those seeking to support them in the lead up to, and eventual failure of, the attempt to pass the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM Act) in 2010. In the media, the courts and Congress, DREAMers were positioned as ‘all American’ young people who were brought to the US through ‘no fault of their own’ and who deserved — unlike their ‘criminal alien’ parents who had ‘sinned’ — to have a pathway to permanent residency opened up to them. For a moment, many DREAMers and their allies strategically invested in this narrative of childhood innocence (and parental blame), as there was a slim hope that it might be the ticket to what could have been an extraordinary legislative helpline for undocumented children. The DREAM Act, however, did not pass, and even its replacement, DACA, signed in 2012, did not offer a similar level of security to undocumented children.

In this moment of legislative loss, the ‘undocumented and unafraid’ movement emerged as a radical response. It outwardly changed the tactics that had been central to many DREAMers. It more openly resisted the discourses that narratively and often materially severed undocumented children from their parents — what I describe in the book as ‘parricide’. An amazing example of this shift is this video of Erica Andiola sitting in protest outside the Trump Tower in New York City, where she declares: ‘We’re going to continue to fight not just for DREAMers, but for our families. We didn’t come to this country alone. We came with our communities. We came with our families. And we’re sitting here to let [Trump] know we’re not going to throw our parents under the bus.’ This shift in tactic beautifully asserted the intersubjective nature of migration and demanded that anti-deportation activists refuse the state’s parricidal logics.

What became really clear is that the failure of the concept of the ‘innocent migrant child’ radically challenges us to re-think our assumptions about what kinds of care get afforded to ‘innocent’ children (and their parents). How do we reconcile the fact that undocumented children are being defended on legislative precedent of being at ‘no fault of their own’ while at the same time the US is spending hundreds of millions of dollars on ‘tender age’ cages rife with sexual, physical and emotional abuse for children crossing the border? What does it mean to sustain an attachment to childhood innocence in a moment when that logic is actively mobilised to deport your parents?

Q: In offering these speculative readings, how do you hope your book will enable readers to sit with the ambivalence of childhood?

I am a queer theorist by training and so it’s really important to me to think not just about the ongoing violences and harms that give tragic contours to how we navigate power dynamics in the day to day, but to also take seriously — and centre — pleasure, hope and alternative futures. In the book I work to produce speculative readings of childhood by drawing on an interdisciplinary array of materials: from scholarship to testimonials, films, newspapers and online blogs, social media, artwork, federal and local law, interviews, autobiographies and personal narratives. This approach is necessary because cultural productions, aesthetics, cinema and creative writing practices of various kinds make possible and proximate the alternative worlds that must come into being for childhood to have a different social and political life.

I hope that my creative and speculative readings of these texts and cultural productions get people to embrace ambivalence as a productive mode of encounter with childhood’s political and psychic life. Part of what makes childhood so easily mobilised within racist, transmisogynist, heteronormative and nationalist thinking is a collective and cultural disavowal of its ambivalence. I hope that Ambivalent Childhoods gets its readers to avow this ambivalence and to engage with it as a dynamic call to imagine new possibilities for childhoods that can — and must — emerge anew.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.