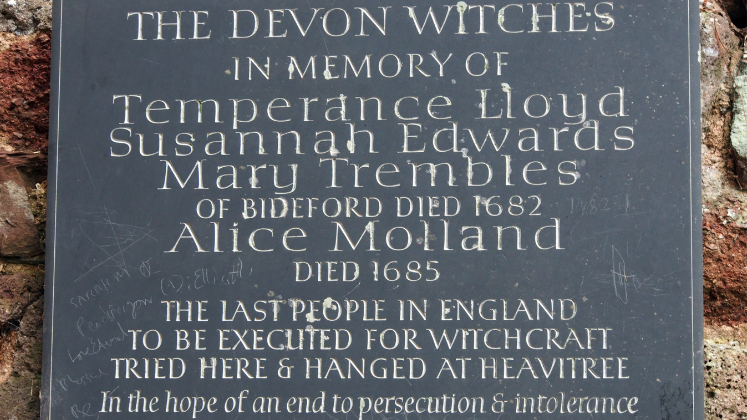

Drawing on his new book, The Last Witches of England: A Tragedy of Sorcery and Superstition (Bloomsbury, 2021), John Callow explores the changing reputation and modern-day memorialisation of the three ‘Bideford Witches’, who in 1682 became the last group of women in England to be executed for the crime of witchcraft.

Recovering the Bideford Witches

The voices of the poor and the dispossessed are rarely listened to in any age. They are too rough, too uncomfortable, too raw and too discordant to sit comfortably within the confines of learned discourse or to be accommodated within the binary, dog-eat-dog logic of the marketplace. Their day-to-day realities of empty bellies, chilled bones, broken sleep patterns and dependency upon the will and charity of others are hardly the stuff of historical romance.

The voices of the poor and the dispossessed are rarely listened to in any age. They are too rough, too uncomfortable, too raw and too discordant to sit comfortably within the confines of learned discourse or to be accommodated within the binary, dog-eat-dog logic of the marketplace. Their day-to-day realities of empty bellies, chilled bones, broken sleep patterns and dependency upon the will and charity of others are hardly the stuff of historical romance.

Over the course of the seventeenth century, we encounter them, more often than not, in court records, when those at the margins of society had broken a law or transgressed an established code of conduct. Moreover, as Lyndal Roper has perceptively and pointedly argued, in the Early Modern period ‘witchcraft trials are one context in which women ‘‘speak’’ at greater length and attract more attention than perhaps any other’. Even then, their words were often interpreted, filtered and shaped by legal procedures and by prevailing notions of what constituted suitable evidence, the rules regarding cross-examination and the extraction of a confession. On occasion, the accused might even be unaware that such conventions existed.

In this light, Temperance Lloyd, Susanna Edwards and Mary Trembles – the three poor women who came to be known as the ‘Bideford Witches’ – were marginal in every sense of the word. Due to their age, gender, economic and marital status and their lack of physical and geographical mobility, they were rendered vulnerable and swept to the sidelines of an increasingly acquisitive society. Unsuccessful and unwanted, they not only lacked the sympathy of others but aroused feelings of either fear or condescension among their contemporaries.

Accused of raising storms, harnessing familiar spirits, forging compacts with the devil and bewitching their neighbours to death, these beggar women were, literally, demonised by their host society. ‘They were’, sniffed one of their judges, ‘the most old, decrepit, despicable, miserable creatures that he ever saw. A painter would have chosen them out of the whole country figures of that kind to have drawn by’. Quarrelsome and querulous, they never thought to deny the charges laid against them and guilelessly dragged each other down in the eyes of the jury.

After their executions for the crime of witchcraft in August 1682, their bodies were dropped into a quick lime pit outside the walls of Exeter to be denied, according to contemporary religious belief, any hope of a resurrection or of life hereafter. Yet, if their bodies were destroyed, then their memory was far from forgotten. It persisted, making Bideford a place still renowned for its witches at the close of the eighteenth century, slowly mutating and growing over more than three centuries to bring the women a recognition, a lasting fame and a form of commemoration that they could hardly have expected or ever dreamed of in life.

Their names are remembered, and their collective biography attempted, while those of their accusers, powerful detractors and judges have slipped from popular consciousness and are now recalled by a mere handful of students of legal history and precedent. Bideford Town Hall takes no civic pride in recalling the justices, the clerk and the mayor who sent the women for trial, yet the names of the three alleged witches are now carved into its cornerstone. Above the razor wire and the concrete bunkers of Greenham Common in the 1980s, the Peace Women chanted the three women’s names and embraced and owned the figure of the once despised witch.

Image Credit: ‘The Devon Witches’ by Chris Nye licensed under CC BY 2.0

It seems that there have been few more remarkable transformations of personal reputation and revaluations of cultural worth to be found in British history than the case of the ‘Bideford Witches’. How has this remarkable shift occurred and what forces was it driven by?

Ironically, it was the extraordinary intensity of popular animosity shown towards the ‘Bideford Witches’ by their neighbours and acquaintances that permitted something of their stories, characters and words to be preserved. These survive in the records of the judicial procedures launched against them in 1671, 1679 and 1682, through the pages of the three main, popular, printed accounts of their trials produced in the autumn of 1682 and in the verses of a near contemporary ballad detailing their crimes.

Though their long lives were telescoped through the lens of the court proceedings, largely in the space of just two months when evidence was taken against them, it is still possible to go in search of the pattern of their lives in the records of the parish, local government and private charities (most importantly, the John Andrew Dole) with which they came into contact. While these sources will not necessarily tell us those biographical details that we might nowadays wish to know, they do permit us to sketch something of the contours of their lives and the context of their sufferings.

Thus, Temperance Lloyd emerges as an abandoned wife and as part of the sudden influx of Welsh immigration to the Devon seaport after the Civil War, prematurely aged and beaten down by a life of unremitting poverty. Susanna Edwards was born illegitimate and widowed young, forsaken by her children and friends; while Mary Trembles was an unmarried and unaccomplished daughter, marooned in Bideford by the deaths of her itinerant, Irish parents. While other women were accused of witchcraft in the outbreak of 1682, accusations of murderous curses and dark magics clung to them because they had no one left to speak for them. Yet, a bungled attempt by ministers, justices and a would-be ‘witch hunter’ at the foot of the Exeter gallows to extract a ‘suitable’ confession to reassure the godly conveyed upon them a sense of dignity and an ability to articulate their plight that, hitherto, they had always been denied.

By the early 1950s, the manifest injustice of their case was used in parliament to demand the repeal of the last witchcraft statutes, while more recently their stories have provided ample points of departure for novelists, radio dramatists and artists. Yet, it was the advent of the second wave of feminism – rippling out to the West Country after the late 1960s – that was responsible for their transformation. If Wicca offered a feminised, and increasingly feminist, form of religion – attuned to ecology and the burgeoning peace movement – then the ‘Bideford Witches’ came to be seen as archetypes of the emancipated and emancipatory witch figure and – by extension – of every woman.

No longer mocked and reviled for her poverty or credulity, the witch had shed the rags that had clung to her over some 400 cruel years. Erudite, confident and sexual (as opposed to sexualised), this new image of the witch figure was primarily defined by feminism but had taken form as the result of the liberties bestowed upon individuals by the European Enlightenment and the imaginative powers unleashed by the Romantic revival. As a consequence, recent grassroots mobilisations – largely but not entirely comprising women’s groups – began campaigns, launched events and gathered petitions that led to the memorialisation of the ‘Bideford Witches’ at Exeter Castle, in their hometown and through the hosting of costumed ‘witches’ picnics’ in the gardens adjoining their onetime prison.

If in life Temperance Lloyd, Susanna Edwards and Mary Trembles had enjoyed precious little rest, justice or contentment, sparking only hatred, resentment and fear in the hearts of those around them, then in the patterns of their modern commemoration they have been associated with all that is spontaneous, irreverent and joyous. The gulf between the historical record and the modern imagery could not be starker or more painful. Yet, against all the odds, a victory of sorts might be found for the ‘witches’ in the laughter of their sisters and their children.

Note: This feature essay gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.