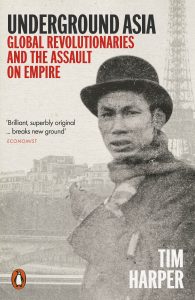

In Underground Asia, Tim Harper explores the intensifying anti-colonial activity across South, Southeast and East Asia that sought to undermine empire ‘from below’ in the opening decades of the twentieth century. Weaving together an amazing array of sources into a memorable and exciting narrative and offering a fresh perspective on familiar events, this is a brilliantly realised work of history, finds Oliver Crawford.

This book review is published by the LSE Southeast Asia blog and LSE Review of Books as part of a collaborative series focusing on timely and important social science books from and about Southeast Asia.

Underground Asia: Global Revolutionaries and the Assault on Empire. Tim Harper. Penguin. 2020.

The decolonisation of Asia was one of the great events of the twentieth century. Today we take it for granted that countries such as China, India and Indonesia are self-governing nation states. But as recently as the 1930s, Bonifacius de Jonge, the Dutch Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia), could say with confidence: ‘We have ruled here for 300 years with the whip and the club, and we shall still be doing it for another 300 years.’ As it turned out, he was wrong. By 1950, Indonesia and India had achieved independence, and a People’s Republic, committed to the overthrow of Western imperialism, had been proclaimed in China.

The decolonisation of Asia was one of the great events of the twentieth century. Today we take it for granted that countries such as China, India and Indonesia are self-governing nation states. But as recently as the 1930s, Bonifacius de Jonge, the Dutch Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia), could say with confidence: ‘We have ruled here for 300 years with the whip and the club, and we shall still be doing it for another 300 years.’ As it turned out, he was wrong. By 1950, Indonesia and India had achieved independence, and a People’s Republic, committed to the overthrow of Western imperialism, had been proclaimed in China.

The tumultuous years of the Second World War and its aftermath loom large in standard accounts of Asian decolonisation. Tim Harper and Chris Bayly covered this ground themselves in Forgotten Armies (2004) and Forgotten Wars (2007). In his magisterial new book, Underground Asia (2020), Harper switches focus to the opening decades of the twentieth century (around 1905-27), from the closing years of Europe’s belle epoque to the jazz age, when, he says, European empires in Asia were ‘fundamentally undermined from below’. These were the years of the First World War and the October Revolution. They were also, as Harper shows, a time of intensifying anti-colonial activity across South, Southeast and East Asia, when assassinations, mutinies, strikes and ‘native’ uprisings caused European officials to fear that the colonial order in Asia might be on the verge of unravelling altogether.

Central to imperial officials’ fears in these years was a new kind of colonial subject: widely travelled, educated in the European style (generally fluent in several languages), well-versed in modern political creeds such as anarchism and Marxism, connected to various international cultural and political networks and implacably hostile to foreign rule. Harper introduces us to many figures of this kind: the Indians Har Dayal, M.P.T. Acharya and M.N. Roy; the Indonesians Semaun and Tan Malaka; and the Vietnamese Phan Boi Chau and Nguyen Ai Quoc. It is this cast of Asian radicals – as opposed to the more familiar pantheon of Asian national leaders, such as Gandhi, Nehru, Mao and Sukarno – whose stories Harper tells in Underground Asia.

Image Credit: Photo by uji kanggo gumilang on Unsplash

The book itself is structured chronologically. The first five chapters span the years 1905-14, when the underground took shape. This happened mainly not in colonial Asia itself but in the cities of Britain, France, Japan, China and the United States, where various Asian anti-colonialists lived, worked, studied and interacted, learning from one another and coming to see ‘Asia’ as a single field of anti-colonial struggle. Chapters Six to Nine cover the First World War, an event that opened new possibilities for resisting imperialism in Asia. At first, certain Indian radicals saw Germany as a promising partner in the struggle against British rule. It was the October Revolution, though, and above all Lenin’s support for Asian ‘national movements’, that transformed the Asian underground. As described in Chapters Ten to Thirteen, communist parties began to form in Asia from 1920, while Asian anti-colonialists such as M.N. Roy, Tan Malaka and Nguyen Ai Quoc soon travelled to Moscow and began engaging (often critically) with the Communist International (Comintern).

The story reaches its climax in Chapter Fourteen, with the National Revolutionary Army’s 1926 Northern Expedition in China and the 1926-27 communist uprisings in Java and Sumatra. Both events, though charged with the promise of emancipation, rapidly descended into bloodshed, ending with a purge of communists in China and the mass execution, arrest and exile of rebels in Indonesia. After 1927, in Harper’s view, there was something of a changing of the guard. A new set of anti-imperialists came to prominence, more committed to party discipline and more nationalist in their politics. With the exception of Nguyen Ai Quoc (better known today as Ho Chi Minh), the careers of those in the underground ended in failure. M.N. Roy was not at the centre of India’s transition to independence. Tan Malaka was killed by political enemies in the Indonesian Republican Army in 1949, in the last months of the Indonesian Revolution. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Java and all but written out of his country’s history during the long reign of the anti-communist General Suharto (1966-98).

Two themes come out strongly from Harper’s account. First, the quality of the everyday life of anti-colonialists – sometimes exciting and even inspiring; often lonely, poor, cold and insecure, lived in fear of deportation or imprisonment by colonial police. Several memorable phrases capture the mood of life in the underground: ‘the world, steerage class’; ‘rebels in rubber soles’; ‘the country of the lost’. The second recurring theme is a sense of the underground’s characteristic politics. These were often ideologically eclectic and tinged with utopianism, from the anarchism of Acharya to the Islamic-communism of Semaun. They were also pervaded by an air of cosmopolitanism, both in the sense that the figures from the underground were often polyglots who drew omnivorously on world culture, and in the stronger sense that they often dreamed a post-imperial future when the world would dispense with the borders violently established by centuries of European imperialism.

I have two criticisms of Underground Asia. The first relates to whether the underground really did ‘undermine’ European rule in Asia, as Harper claims. Looking at Indonesia, in 1927 European rule was still firmly in place across the archipelago. Indeed, as a result of the failed 1926-27 uprisings in Java and Sumatra, it would be buttressed further by new police and censorship powers. It was not until the Japanese defeat of the Dutch in 1942 and subsequent occupation of Indonesia (1942-45) that the real tipping point came for the Indonesian independence struggle.

My second criticism concerns political violence. Harper acknowledges that Tan Malaka, not uniquely among the figures discussed in the book, saw violence as ‘a revolutionary necessity’. He also argues, however, that Tan Malaka believed Dutch rule might be ended by ‘the suborning of military garrisons, the solidarity of general stoppages, the unstoppable momentum and moral force of mass demonstration’ (543). Undoubtedly Tan Malaka hoped that violence might not be necessary to end foreign rule, but surely understood that ‘moral force’ alone was unlikely to be sufficient. In his writings he was fulsome in his praise of the Bolsheviks and, later, the Chinese Communists under Mao, neither of whom shied away from violent (and highly authoritarian) methods of achieving their political goals. This ought to remind us that the politics of the Asian underground, though focused on emancipation, had a darker side – one that Harper might have dwelt on longer.

These caveats aside, Underground Asia is a brilliantly realised work of history. It weaves together an amazing array of sources into a memorable and exciting narrative, offering a fresh perspective on familiar events and bringing to life a cast of historical actors who are too often forgotten in their own national histories.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.