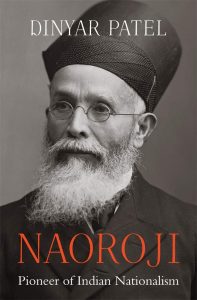

In Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism, Dinyar Patel offers a new biographical study of the groundbreaking politician Dadabhai Naoroji, a nineteenth-century activist who became an influential critic of British imperialism, a key founding figure in the Indian nationalist movement and the first Indian MP elected to the British Parliament. Drawing on extensive research to detail Naoroji’s long life and accomplishments, this extraordinary biography presents a rounded portrait of a true ‘Pioneer of Indian Nationalism’, writes Ramnik Shah.

Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism. Dinyar Patel. Harvard University Press. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Like most South Asians in the diaspora of my generation born during World War II, one had grown up hearing the name Dadabhai Naoroji (Naoroji), but only superficially, as the first Indian to be elected to the British Parliament way back in the 1890s. This simple fact took on historic significance, nearly a hundred years on, as the image of the immigrant communities in the UK began to change with the arrival in 1987 of a pioneering group of four non-white MPs: Keith Vaz, Diane Abbott, Paul Boateng and Bernie Grant. But even then there was precious little generally known about Naoroji’s background and trajectory.

Like most South Asians in the diaspora of my generation born during World War II, one had grown up hearing the name Dadabhai Naoroji (Naoroji), but only superficially, as the first Indian to be elected to the British Parliament way back in the 1890s. This simple fact took on historic significance, nearly a hundred years on, as the image of the immigrant communities in the UK began to change with the arrival in 1987 of a pioneering group of four non-white MPs: Keith Vaz, Diane Abbott, Paul Boateng and Bernie Grant. But even then there was precious little generally known about Naoroji’s background and trajectory.

Dinyar Patel, Assistant Professor of History at the SP Institute of Management Research in Mumbai, has filled that void admirably in this book. It will be of great interest to students of economics and political science as well as of Indo-British history. It draws the reader into Naoroji’s huge hinterland of knowledge, writings and achievements. What comes across is Naoroji’s passionate commitment to the concept of (an) Indian nationhood within the parameters of the British rule, then at the height of Empire, that came to dominate his life. In this he was driven by an abiding concern for the poverty-stricken state of his country under the Raj. It was this that was to spearhead his political activism after first landing in Britain in 1855. Over the next 52 years he divided his time between Britain and India, with increasingly longer spells in Britain as he consolidated his political credentials and gained wide name recognition in the public sphere and in the corridors of power.

Naoroji was born in 1825 in a native area of Bombay to Parsi parents who had moved there to escape rural poverty from their ancestral Gujarat, and he received his early education at a local English medium school as a non-fee-paying pupil. In May 1840, he was enrolled at the prestigious Elphinstone College, having been awarded a special scholarship on account of his proficiency in mathematics. He excelled at Elphinstone, which became his alma mater. After finishing his studies in 1845, he was invited to teach there, and following a series of rapid promotions, he ended up as professor of mathematics and natural philosophy, ‘becoming the first-ever Indian to hold this rank at a British-administered institution of higher education’ in India (272). He also supervised a girls’ school and was made a member of the Bombay Board of Education.

It was also during this period that his political thinking began to take shape, first publicly expressed at the inauguration of the Bombay Association in 1852 when he ‘suggested a link between faulty governance and poverty’ (61), which he was to later articulate quite forcefully and with confidence.

But then came an abrupt change when he abandoned his promising academic career and departed Bombay for Britain in 1855 with a fellow Parsi to set up the first Indian commercial firm in Britain to trade in the growing cotton export market. In 1856 he was appointed Professor of Gujarati at London University and re-entered the world of academia as an adjunct to his business.

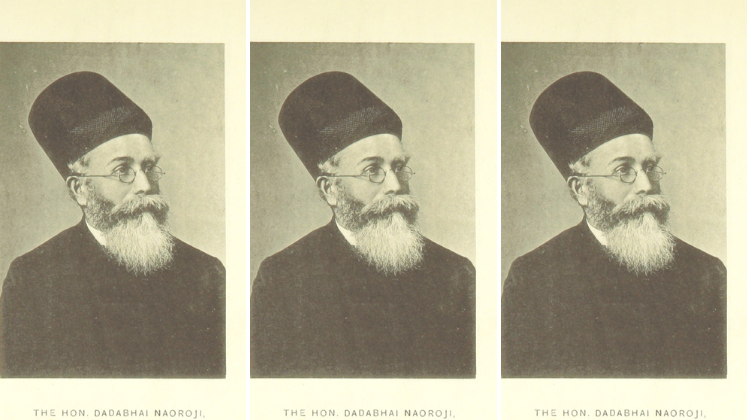

Image Credit: Photograph titled ‘The Hon. Dadabhai Naoroji’ from India, Past and Present, historical, social and political … Illustrated, etc. Courtesy of British Library, identifiers 003239093 (physical copy) and 014828895 (digitised copy) (British Library, no known copyright restrictions).

So what form did his political activism take? Very soon after arriving in Britain in the mid-1850s, he joined certain societies ‘where he emerged as an academic and […] popular authority on all matters subcontinental [… and] helped create institutional space in the imperial capital for discussion of Indian affairs’. More importantly, in 1866 he founded the East India Association – which brought together British Indian officials of the highest calibre and leading Indian figures from across a broad spectrum of opinion and expertise in the law, journalism, education and industry. Its key function was to lobby MPs on Indian policy and to act as a cultural bureau and ‘clearinghouse for information on India, a resource for the public as well as Parliament’ (126-28).

From here on, Naoroji picked up his theme of the linkage between British rule and Indian poverty, developing and pursuing it relentlessly over the next three decades under his generic ‘drain of wealth’ theory of ‘thoughtless and pitiless action of […] British policy […] the pitiless eating of India’s substance […] and the further pitiless drain to England’ (9). He argued that civil servants’ salary and pension remittances to Britain, profound unfavourable trade balances, the cost of the military deployed to defend British possessions outside India, the siphoning of substantial amounts of Indian tax revenues to imperial coffers and the like all contributed to this one-way traffic (62-63).

Naoroji presented papers, gave talks, engaged in discussion and correspondence with a whole range of high-ranking government officials and MPs, appeared before Parliamentary committees, made representations to any number of other bodies and organisations and was asked to join in delegations and deputations concerned with matters Indian, as well as much more.

Naoroji’s Elphinstonian cohorts and others in the higher echelons of native Indian society had come to the conclusion that administrators of the Raj were too inflexible and indifferent to the needs and interests of those over whom they ruled. In the absence of any platform for raising issues of governance and accountability, the Indians felt that they had to take their case direct to the British home public and policymakers for any meaningful change. In this context, while the idea of Indian MPs in the British Parliament was nothing new, as we learn from Chapter Three of the book (‘Turning toward Westminster’), it was Naoroji who gave bold expression to it in his 1867 paper, ‘England’s Duties to India’, bemoaning ‘the almost total exclusion of the natives from a share and voice in the administration of their own country’ (92), unlike the ‘rights of representation [enjoyed] by other colonized people in the French, Spanish, and Portuguese empires’ (94).

This was the prelude to Naoroji’s foray into politics proper, the impact of which was to reverberate well into the next century. The book charts his path to becoming the first Indian MP in the British Parliament in great depth and detail. It had been a long and arduous journey, full of setbacks and challenges involving rival contenders from within his own Liberal Party as well as from Conservative opponents. In one notorious incident, in November 1888, he was called a ‘black man’ by none other than the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, when Salisbury stated that he did not believe the UK electorate would vote for Naoroji. That racist slur elicited such widespread opprobrium from high-profile and other enlightened folk that the National Liberal Club held a dinner in Naoroji’s honour as a response to the insult (166-67).

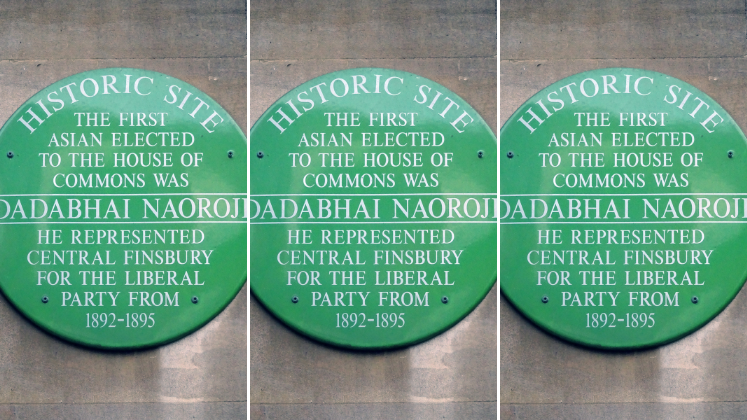

Naoroji had been chosen as the Liberal candidate for Holborn at the 1886 general election, which he lost, but he eventually fought and won the 1892 election as MP for the Central Finsbury constituency, albeit with a wafer-thin majority and for one term (1892-95) only. It had not been an easy ride: he had been subjected to all manner of dirty tricks, internal party strife and other distractions.

By then, however, Naoroji had acquired such stature that he was hailed by both Indians and Britons alike as the ‘Grand Old Man (GOM) of India’, a contemporary reference to Prime Minister William Gladstone as the United Kingdom’s GOM (190). Even across the Atlantic, the New York Review of Reviews, in its issue of October 1892, carried an imposing sketch depicting Naoroji as a colossus straddling England and India in his new-found role as a British MP (pictured on page 191), popularly dubbed ‘Member for India’.

Image Credit: Altered image of ‘Green plaque at Old Finsbury Town Hall, Rosebery Avenue, Clerkenwell, London EC1R 4RP’, celebrating Dadabhai Naoroji’s election to the House of Commons. Image by Spudgun67 licensed under CC BY SA 4.0

But Naoroji was a great deal more than that: he had an equal parallel standing in India as a leader and as a founding member of the Indian National Congress in 1885. He was thrice honoured to preside over annual sessions of the Congress: 1886 (Calcutta), 1894 (Lahore) and 1906 (Calcutta again). In December 1893, he had received a heroic welcome at Bombay on his first return visit to India as an MP and all the way on his whistle-stop train journey to Lahore for the Congress session. He was similarly feted in subsequent years as well.

Naoroji remained an influential player in the nationalist movement that was gathering momentum at the turn of the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. By this time he was also becoming unsparing in his radical demand for Indians to be compensated for their past sufferings and be recognised as worthy of equal status as subjects of the Empire. In his last address to Congress at the 1906 Calcutta session, he enunciated this as ‘Self-Government or Swaraj’ on a par with that of the UK and the dominions of Canada and Australia.

Bear this in mind: he lived through all of Queen Victoria’s reign and beyond. After first coming to Britain in 1855, he made several trips back and forth, when travel and communications between Britain and India took weeks at a time. He lived a dual existence, with home, business and political activities spread across the two countries, with all that this entailed in practical and financial terms. He also had to struggle with frequent bouts of ill health, family bereavement and other crises.

Naoroji lost his seat at the 1895 election. Thereafter he missed the 1900 election due to illness, then contested the January 1906 election at North Lambeth as an independent Liberal but lost badly. That, however, was not the end of Naoroji as a political avatar, but after a further year of poor health, he finally left Britain in October 1907 to return for good to India where he retired and died in 1917.

There is so much packed into this book that no review can do justice to the complex narrative of Naoroji’s long life and accomplishments, all graphically captured in this extraordinary biography. The author’s extensive research has enabled him to produce a timeline of Naoroji’s whole lifespan, including all significant events and turning points in his personal life and a comprehensive list of his papers and talks, short sketches of key individuals, a note on sources, copious endnotes and a useful index. The endorsements on the back cover by distinguished academics and historians – Ramachandra Guha, Steve Beckett, Farrukh Dhondy and Sunil Khilnani – are an impressive testament alone to Patel’s brilliant creation.

In Naoroji, then, Patel has constructed a rounded portrait – on the basis of surviving records, traceable sources and a whole host of other documented material, all properly referenced – of a true ‘Pioneer of Indian Nationalism’ indeed: a hero and role model not only to his contemporaries but also to future leaders like Gandhi and Jinnah, who had touched base with him and who later came into their own to complete the nationalist struggle. This timely publication should appeal to both Britons and Indians alike in the light of our renewed national focus on Empire.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.