In Human Shields: A History of People in the Line of Fire, Neve Gordon and Nicola Perugini explore how the use of human shielding in conflict zones, as part of protests and in virtual computer game scenarios unsettles our understanding of the ethics of war. This absorbing study offers a thorough analysis of some of the persistent questions regarding the conduct of modern warfare, the evolution of international and humanitarian law and the legal status of civilians in conflict zones, writes Joanna Rozpedowski.

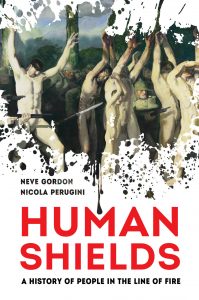

Human Shields: A History of People in the Line of Fire. Neve Gordon and Nicola Perugini. University of California Press. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

Is killing civilians legally the same as killing human shields? Can a population’s race or ethnicity shape Western interpretations of how international law should be applied in conflicts? What does the posthuman turn — where the enemy on the battlefield is subject to extended surveillance and constitutes a mere amalgamation of electronic data signals — tell us about the future of war and international law? To these and other highly nuanced and challenging questions, Neve Gordon and Nicola Perugini offer compelling answers in Human Shields: A History of People in the Line of Fire.

Is killing civilians legally the same as killing human shields? Can a population’s race or ethnicity shape Western interpretations of how international law should be applied in conflicts? What does the posthuman turn — where the enemy on the battlefield is subject to extended surveillance and constitutes a mere amalgamation of electronic data signals — tell us about the future of war and international law? To these and other highly nuanced and challenging questions, Neve Gordon and Nicola Perugini offer compelling answers in Human Shields: A History of People in the Line of Fire.

Human Shields is a dense study of the evolution of international law concerning civilian life. The authors attempt to show how the frequent resort to human shielding in active warzones, antinuclear and environmental protests and virtual computer game scenarios unsettles our understanding of the ethics of war and the acceptable limits of the profoundly paradoxical notion of ‘humane violence’. The book is academic yet accessible and should be of interest to an interdisciplinary audience seeking both a historical and contemporary analysis of the legal status of civilians across time and conflict situations.

The question of the status of civilians and their use as human shields in conflict is neither new nor especially original in the international law literature. An inventory of humanitarian instruments from the Lieber Code of 1863 to the 1907 Hague Convention, the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the 1977 Additional Protocols shows that these offer protections to non-combatants and enshrine prohibitions on the use of human shields in international and non-international armed conflict.

Yet, according to the United Nations, in 2021 alone, some 11,000 civilians were killed in twelve conflicts; nearly 90 per cent of wartime casualties in present-day conflicts are civilians. In Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Iraq, Nigeria, Syria and South Sudan, civilian deaths are often caused by improvised explosive devices, persistent, deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on schools, hospitals and residential buildings, food insecurity and the secondary effects of disruption to water, sanitation and health services.

Image Credit: Photo by Rodrigo Perez on Unsplash

Routine breaches of international humanitarian law are a frequent topic of discussion at international multilateral meetings, academic colloquia and in the media. Civilian bodies in the political act of civil disobedience or military conflict are scrutinised and written about in their many concrete incarnations: as involuntary weaponised shields for ISIS fighters (Chapter 16), as voluntary Greenpeace activists shielding whales (Chapter 10), as veterans acting as human shields at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation (Chapter 22), as mother-and-child human shields at a US-Mexico border (Chapter 19) or as transnational activists shielding Palestinian homes against the encroachments of Israeli bulldozers (Chapter 11). Human shields can thus be deployed as a war tactic or as an anti-war strategy of non-violent resistance. Therein lies the crux of the legal controversy: the drawing of appropriate distinctions between human shielding as an inhumane and coercive act of violence inflicted on innocent civilian bodies in war and shielding as a ‘living wall’ against war itself.

Human shielding as a ‘weapon of peace’ featured in the anti-war strategy during the Sino-Japanese War, which gave rise to the idea of ‘The Peace Army’. Following Japan’s invasion of China in 1931, Western suffragists urged unarmed volunteers to enter conflict zones and place themselves amongst the combatants to create a buffer between warring parties (55). Some twenty years later in 1948, the UN Security Council deployed UN military observers to the Middle East to monitor the Armistice Agreement between Israel and its Arab neighbours. The idea of sending ‘an unarmed body of soldiers of peace’ (56) was thus formally institutionalised as UN peacekeeping.

Whether it be the US Civil War of the nineteenth century, World War II of the twentieth or the Sri Lankan killing fields of the twenty-first, however, the deployment of human shields and relentless targeting of civilians and civilian facilities have been a dramatic constant that features conspicuously in strategic military calculations. ‘In assessing the balance between military advantage and civilian harm’, Gordon and Perugini note, the deaths of civilians have rarely been of consequence. Rather, a steadily common strategy in the ambiguous economics of scale of any war machine has been to ‘decrease the legal value of civilians who are killed as human shields’ by ‘increase[ing] the number of civilians who are considered human shields’ (150).

In manipulating the categories assigned to human life subjected to formidable lethal force, military strategists can legitimise the killing of many thousands of defenceless civilians, Gordon and Perugini argue, while maintaining an aura of requisite proportionality and necessity: in short, of legality. In like manner, they argue that the denial of civilian casualties whose deaths had been incidental to an otherwise lawful attack has become increasingly prominent in the twenty-first century, due to the development of new warfare technologies and corresponding new guidelines tested in post-9/11 conflict scenarios.

The US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have undeniably increased both insurgents’ deployment of human shields and the number of civilian deaths, often explained away by the world’s largest military force as ‘collateral damage’. The ‘global war on terror’ conducted in conventional and unconventional theatres of war has increased the use of human shields by irregular armies and obfuscated the principle that distinguishes combatants and non-combatants.

This, in turn, has compelled the US to regard human shielding as a ‘perfidious weapon of the weak’, enabling it to modify and adapt the army’s proportionality calculations and thus ‘legitimize the anticipated increase of harm to civilians’ (136) by shifting responsibility for civilian casualties to those who deploy them. In so doing, US troops have been deemed by their command superiors and the Judge Advocate Generals to be fully justified in deterring a perverse usage of human shields by equally perversely attacking them (137) under the principle of military necessity, all the while ignoring the principles of proportionality and distinction. Such practices reveal how the law itself can facilitate and instrumentalise lethal force where civilian lives are subject to a calculation of value at best precarious, at worst clinically statistical.

The principle of distinction is complicated by several types of human shields in use in modern-day conflicts. Gordon and Perugini draw our attention to first, proximate human shields or civilians who become human shields due to ‘proximity’ to a legitimate target ‘without doing or being forced to do anything’ (160); second, voluntary human shields who choose to protect military targets; and third, involuntary human shields who do not possess any agency or choice in such an action. In the rapidly evolving terrain of warfare, international law’s distinctions between combatants and civilians become readily obscured and the volatility and complexity of urban warfare expose increasing numbers of civilians to proximate human shielding. That is why, the authors contend, proximate shielding has been invoked to legitimise increasingly inhumane violence, with 99 per cent of global conflict casualties between November 2015 and October 2016 constituting ‘proximate’ civilian shields (162).

As if appalling violence inflicted on nonbelligerent populations was not morally revolting enough, the authors point out that we may now be entering an era of ‘posthuman shielding’ (184). The ‘gamification of combat’ (201), drone joystick wars, algorithmic decision-making and systematic failures of sophisticated technological systems have steadily led to a version of ‘virtual barbarity’ (206), prompting the reframing of ‘civilian’ casualties as the far more unsentimental ‘enemies killed in action’. The introduction of extralegal categories to befit the new predictive war-fighting paradigm attempts to normalise habits and dispositions that romanticise human shielding in conflict scenarios or altogether blunt righteous indignation against civilian loss of life. As such, these new categories are antithetical to Western warfare norms which uniformly condemn such practices.

This reliance on new (posthuman) surveillance and reconnaissance technologies, new intelligence-gathering applications, use of satellite data, (dis)information campaigns, the expanded role of defence and humanitarian sector entities and the formation of mercenary groups and private armies in the twenty-first century: these all saturate the modern battlefield with new actors, means and methods of combat and duly complicate their status and responsibility under existing international laws.

Whilst the breadth and depth of Human Shields are astonishingly exhaustive, another virtue of the book is its timing. Since the launch of the so-called ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine, there has been a resurgent interest in international criminal and humanitarian law. The authors’ compelling narrative and absorbing study may not draw glib and comforting conclusions, but it does offer a thoroughly researched answer to some of today’s persistent questions regarding the past, present and future conduct of war, the ethics of humane violence and the legal status of civilians in war zones.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Banner image credit: Pixabay CCO