In Passport to Peckham: Culture and Creativity in a London Village, Robert Hewison digs deep into the history of a contested part of London known for its art scene as well as the challenges of urban regeneration and related gentrification. Bringing together social, cultural, architectural and political history, this book gives readers a passport to journey through the multicultural, multifaceted and dynamic Peckham, writes Niclas Hell.

Passport to Peckham: Culture and Creativity in a London Village. Robert Hewison. Goldsmiths Press. 2022.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

The precarious housing market and the support given to cultural professionals were two of the most heated debates in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Writing a book on the history of a confined area in South East London, Robert Hewison must have felt strangely in tune with these global issues. A cultural historian, Hewison has predominantly published about John Ruskin, but he has also written broadly for newspapers and think tanks on culture and history. His influential 2014 book helped popularise the term ‘cultural capital’ for a wider audience.

The precarious housing market and the support given to cultural professionals were two of the most heated debates in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Writing a book on the history of a confined area in South East London, Robert Hewison must have felt strangely in tune with these global issues. A cultural historian, Hewison has predominantly published about John Ruskin, but he has also written broadly for newspapers and think tanks on culture and history. His influential 2014 book helped popularise the term ‘cultural capital’ for a wider audience.

In his new book, Hewison explores Peckham, a place with an extraordinary concentration of underground and high-brow culture. The word ‘place’ is warranted: no lasting administrative designation has ever been called Peckham. Despite this, there is a strong local identity, and Peckham is the word used in the media and everyday speech to refer to the area. Hewison settles for describing Peckham as a ‘village’, as seen in his book’s subtitle. In Passport to Peckham, we follow him on a journey through time, urban planning, social deprivation, cultural exuberance and rebirth.

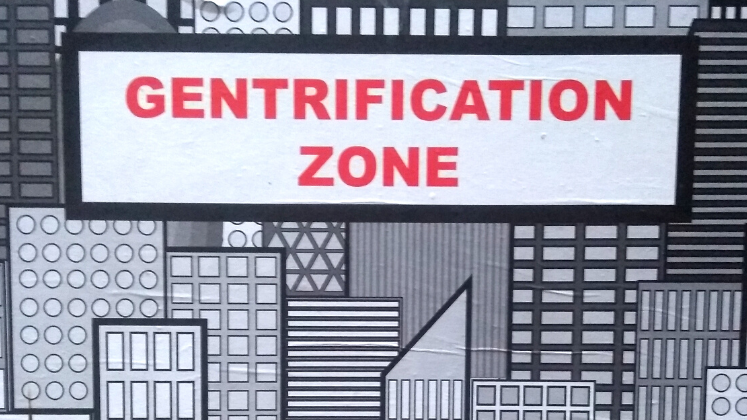

Hewison does not write Peckham’s history with the unconditional love (or love-hate) of someone who grew up in the area – he literally starts the book by telling us that he does not live or work there. Neither is it an academic review of the facts pertaining to Peckham. The book is, in one sense, a microhistory of the area, establishing its architectural history and general timeline. Just as any good microhistory, Passport to Peckham asks the ‘large questions in small places’, as Charles Joyner put it. Peckham has borne witness to important currents in the late-twentieth-century art world, with the successes and controversies of a young Damien Hirst explored in the book, as well as the consequences of multicultural Britain, deindustrialisation and the ensuing gentrification of cities and their outskirts.

Thematically exploring different faces of Peckham, each chapter gradually builds the understanding of a new aspect of the area: its early history, urban planning, the cultural scene. The advantages of this approach do not appear until somewhere in the middle of the book, when the different styles of the chapters start appearing as freestanding sequels to the others. Many aspects of Peckham deserve an essay of their own, and they receive one in this book.

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Welcome to Peckham’ by Matt Brown licensed under CC BY 2.0

Chapter Four explores the historical context of art and creativity in Peckham. A substantial part of this background is the foundation and development of the surrounding art schools and galleries, of which Goldsmiths’ College is the most notable and well-explored (the book is published by Goldsmiths Press). Around the turn of the last century, individual art studios, galleries and Goldsmiths were all opened within a few years of each other, paving the way for a South London art district. This chapter, among others, paints a picture of Peckham as an underdog. Full of ideas, creativity and resourceful individuals, yes, but positioned on the relative periphery, delaying it from realising its full potential.

Chapter Six applies the background knowledge from the first chapters to discuss the urban renewal of the 1990s and 2000s. Neither a potential site for waterfront development nor a candidate for the full-scale culture-led or wellbeing-oriented trends in urban regeneration, the urban renewal in Peckham was mainly aimed at clearing out rundown houses. Portions of Peckham were ‘rife with drug use, raddled with squatters, rigid with racial tension, and avoided by a frightened and corrupt police force’. The 1980s and its crescendo of social problems led to ambitious renewal projects in the coming decades.

There has been a cultural varnish provided by the creations of local and international artists being inserted into the public space. Despite this, the key renewal projects in Peckham were primarily brick-and-mortar developments. The relatively close Canary Wharf and its hyper-regenerated skyscrapers of the same era cast their shadow over the more modest projects in Peckham.

The physical book does not seem meant to be read in one passionate stint. The chapters paint different pictures of a multifaceted Peckham, and the intended bite-sized reading experience is underlined by the book being set in a dense sans-serif font, making reading a bit slower as well as giving the text a coffee-table book aura. It is not a particularly large book, but nicely bound. There are many images, but they are all in black and white. It seems the book, like Peckham, is a product of creativity, with some spartan and some flamboyant features.

Peckham seems to march in step with major developments. For an urban studies academic, there are a couple of especially clear examples of this. First, the extraordinary rise in housing prices during the last decades. Second, the tension between the majority and other social, ethnic and cultural groups: embracing what makes a place unique or shunning what makes it unfamiliar. This is elegantly discussed by Hewison, giving voice to both sides of the arguments, whilst also making us aware of his own opinion.

In this sense, the book does not shy away from taking a stand politically. The ‘neoliberal’ reforms of the 1980s are treated with disdain. Gentrification is discussed from several angles, but the drone pipe of displacement and privilege – with Hewison even quoting Caleb Femi’s poem ‘Coconut Oil’ calling gentrification ‘chemotherapy’ – constitutes the basis for these chapters. In no way, though, is the book a manifesto against certain types of urban planning. Rather, readers get the sense that Hewison wants to be intellectually honest about his own viewpoints. Positive perspectives on gentrification for Peckham’s black community are also discussed in the conclusions, and the dismissive tone against ‘Mrs. Thatcher’ and her time do not make the book a political pamphlet.

Passport to Peckham gives us just that – a passport to access dynamic Peckham. Hewison does not let Peckham become stylised or cast into any existing stereotypes. Instead, the multicultural, multifaceted place of yesterday and today speak and are spoken to. This book remains thoroughly about the London ‘village’ of Peckham and its creative residents rather than the political and cultural history of wider Britain. Providing food for thought on contemporary debates on urban development, social deprivation and the value of culture, reading this book makes Peckham seem a little more at the centre of the universe than before.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Banner image credit: Crop of ‘Rye Lane. Peckham, London © Mels van der Mede’ by licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0