In this post celebrating the start of Black History Month in the UK, Mohamad el-Harake reviews The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois: Racialized Modernity and the Global Color Line by José Itzigsohn and Karida L. Brown, which advocates for the importance of a Du Boisian sociology that recentres race, class and colonialism at the heart of sociological analysis with the goal of undoing the global colour line and all forms of oppression, patriarchy and exclusion.

The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois: Racialized Modernity and the Global Color Line. José Itzigsohn and Karida L. Brown. NYU Press. 2020.

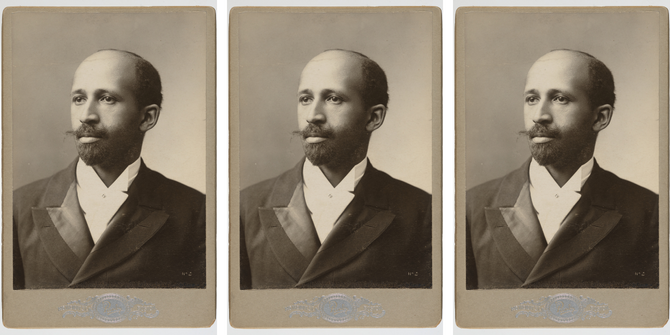

Embarrassingly, I had only encountered W.E.B Du Bois once before starting my graduate courses. It was through a lecture given by Aldon Morris, a Du Boisian scholar, at the American University of Beirut at a public event called ‘W.E.B Du Bois at the Center’. Du Bois the scholar, the activist, the architect of sociology, never appeared in my undergraduate studies. This absence is, unfortunately, systemic. It can be seen from university curriculums denying Du Bois any credit in the founding of sociology to sociological analysis negating the role that race and colour have played in US politics and history, on which Du Bois was a profound voice.

Embarrassingly, I had only encountered W.E.B Du Bois once before starting my graduate courses. It was through a lecture given by Aldon Morris, a Du Boisian scholar, at the American University of Beirut at a public event called ‘W.E.B Du Bois at the Center’. Du Bois the scholar, the activist, the architect of sociology, never appeared in my undergraduate studies. This absence is, unfortunately, systemic. It can be seen from university curriculums denying Du Bois any credit in the founding of sociology to sociological analysis negating the role that race and colour have played in US politics and history, on which Du Bois was a profound voice.

The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois: Racialized Modernity and the Global Color Line, written by José Itzigsohn and Karida L. Brown, is ever more needed in today’s postcolonial moment. The book reimagines this Du Boisian denial. It is a concerted effort at advocating for the centrality of a Du Boisian sociology that invites a rearticulation and reconfiguration of how sociology is normally done.

The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois offers an invaluable analysis of Du Bois’s corpus and magisterial conceptualisations in a 21st-century framework. The book sometimes comes across as biographical, and at other points theoretical and epistemological. Combining the two is one of the main purposes of the book. Du Bois developed a socio-historic analysis based on a phenomenological and experiential lens – for example, in his auto-ethnographic book Dusk of Dawn, he ventured to link his life to the ‘larger historical events in which it unfold[s]’ (58). From that, the book also focuses on excavating the tenets of a Du Boisian theoretical and empirical sociology that uses social science to undermine biological and cultural racism.

Even though these are admirable contributions in their own right, the strength of this book lies in presenting a manifesto for a contemporary Du Boisian sociology. That is, a ‘collective’ and ‘reflexive’ endeavour aiming to recentre race, class and colonialism at the heart of sociological analysis in order to undo ‘the color line and all forms of oppression, patriarchy, and exclusion’ (211).

This synthetic sociology is based upon Itzigsohn and Brown’s assertion of two axes to Du Bois’s thought. First, Du Bois is a theorist of ‘racialized modernity’. He developed a sociological analysis that places racism and colonialism at the centre of any analytic study, contending that they are ‘the pillars upon which the modern world was constructed’ (1). This argument subsumes Du Bois’s famous conceptualisations of three key terms: ‘double consciousness’, the ‘veil’ and ‘second sight’. How Du Bois worked with these concepts and how they were formed and neglected by his contemporaries, such as William James, George Herbert Mead and Charles Horton Cooley, is the subject of the first two chapters.

Taking the biographical account into a broader analysis of global structures, the book highlights the false dichotomy separating theory — the scholar — and practice — the activist. This argument is anchored in the liberal separation of epistemology (to know) and ontology (to be). This, in turn, prevents the scholar from actually participating in what one preaches. The book takes this as a defining feature of Du Bois as a ‘Scholar Activist, an Activist Scholar’ who participated in organising conferences (such as for the NAACP), educating youth (in writing books for children) and, at the end of his life, directing ‘the writing of the Encyclopedia Africana’ (12) at the invitation of Kwame Nkrumah. The book contends that Du Bois was able to go beyond the modern activist/theorist distinction, merging experiential and concrete struggles (such as Pan-Africanism) with abstract ambitions.

The second point of emphasis is the globalised perspective. The authors read this into the work of Du Bois, stating that he saw the historical construction of race as a global phenomenon continuously intermingling the intersectional aspects of racialisation, colonialisation and globalisation. Hence Du Bois’s infamous statement that ‘the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line, the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea’ (31). It was only after he realised that the colour line is ‘global’ and ‘place-specific’ that the authors claim his belonging became not to the United States, but to the ‘Africana diaspora and the Global South as a whole’. This is a marker of Du Bois’s planetary thinking.

The book culminates in the chapter, ‘A Manifesto for a Contemporary Du Boisian Sociology’. This chapter does not invite an inclusive approach where Du Bois is merely added to the existing sociological canon, nor an orthodox Du Boisian sociology where we position the panacea as the strict implementation of a Du Boisian vision. Rather this is a sociology that is, at its roots, a ‘collective endeavor’. It is a critical and activist approach centred on a firm stance against racism, colonialism, oppression and inequality in all its shapes and forms, whether in the past, present or future. It is a sociology that grounds itself in concrete struggles, channelling knowledge to the betterment of the oppressed and the have-nots. Most importantly, it is a sociology that affirms the phenomenological approach of critiquing modernity from the perspective of its racialised ‘other’, and it transcends Du Bois to further account for religion, gender, patriarchy and sexuality as central axes of sociological inquiry.

What I believe the authors overlook is a close examination of the ways in which we must move forward. In other words, the ways of resisting the current practice of sociology informed by racialised modernity, and of ensuring that we do not fall into the tropes of colonial imaginaries. Using a Du Boisian vocabulary, how might we develop a second sight that breaks through the veil to see the humanity of the dehumanised? The themes of resistance, violence and revolution were somewhat sedated and moved to the backseat in the book, even though they hold great sociological weight in unsettling any notions of racialised modernity. For example, examining how sociology can make use of inter- and intra-continental dialogue, such as North-South and South-South exchange, is of great importance in growing beyond normative colonial modernity (see also Boaventura de Sousa Santos, 2018). To not move into the exteriority of modernity impedes the process of changing the present conditions we live in.

Nonetheless, The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois demonstrates the weight of denying a scholar like Du Bois his epistemic contributions to the field of sociology. This disavowal enabled the phenomenology of whiteness to take control of who gets to become human and who does not. The book also makes visible what undergirds today’s sociological analysis. To imagine an alternative sociology is to reconfigure what we centre and decentre in our sociological imagination. To take race, class and colonialism seriously enables us to undo epistemic and racial inequalities and allows us to march towards the ‘unfinished project of decolonization’ (see also Ramón Grosfoguel, 2008).

In this sense, The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois doesn’t bow to the audience and close its doors at the end. Rather, it invites its readers to collectively reimagine what sociology ought to be when the oppressed are taken as its object of analysis. It invites a sociology that is ‘in the process’, where we, not the authors, are responsible for answering the question of what it means to rehistoricise W.E.B Du Bois into an alternative, contemporary Du Boisian sociology. I call upon those interested in going beyond the modern Eurocentric sociological canon to engage with this book in a manner geared towards liberation from a racialised world.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Very interesting