In Writing and Rewriting the Reich: Women Journalists in the Nazi and Post-War Press, Deborah Barton explores how women journalists contributed to the Nazi press and its propaganda goals. The book illuminates the historical role women journalists have played in permitting the actions of totalitarian regimes, writes Christina Obolenskaya.

Writing and Rewriting the Reich: Women Journalists in the Nazi and Post-War Press. Deborah Barton. University of Toronto Press. 2022.

Women’s columns have long been perceived by culture to be frivolous, starting with one of the first popular advice columnists, Dorothy Dix, in the early 20th century to the contemporary author Candace Bushnell. At the start of World War Two, the Nazis invested in the women’s column, but for a much more sinister reason than ensuring that women had a steady stream of dating advice. Although the frill patterns of a curtain would seem to lay outside the purview of the Nazi regime, articles covering decorating, fashion and relationship advice served a political purpose.

Women’s columns have long been perceived by culture to be frivolous, starting with one of the first popular advice columnists, Dorothy Dix, in the early 20th century to the contemporary author Candace Bushnell. At the start of World War Two, the Nazis invested in the women’s column, but for a much more sinister reason than ensuring that women had a steady stream of dating advice. Although the frill patterns of a curtain would seem to lay outside the purview of the Nazi regime, articles covering decorating, fashion and relationship advice served a political purpose.

In Writing and Rewriting the Reich: Women Journalists in the Nazi and Post-War Press, Deborah Barton, a historian at the Université de Montreal, explores how female journalists were enmeshed in hierarchies of oppression under the Nazi regime. Women journalists held a key role in the Nazi press, providing the state direct access to Germany’s women.

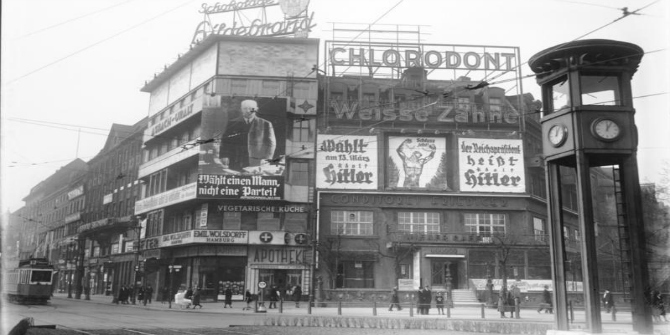

Adolf Hitler argued in Mein Kampf that rewiring a citizen’s political education stems from the efforts of the press. He understood the critical role that the press played in manipulating the masses, and he undermined journalistic integrity by restructuring the German press in 1933. The Nazis accused Jewish people of dominating German public discourse, ousted Jewish journalists and closed papers belonging to the Social Democratic and Communist parties.

While limits were set on women entering the legal and civil service, women did not face explicit restrictions in journalism. The Nazi press created the Committee of German Women Journalists, a sub-department of the German Press Association, founded in 1934 and led by Annie Juliane Richert.

At the time, women were seen to possess a level of empathy that men were incapable of tapping into with their writing. In November 1933, Munchner Neueste Nachrichten published an article titled ‘Women as Journalists’, which told the story of the British newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe. He believed that women were suitable for journalism given their levels of compassion, but that they could only handle the ‘lighter side of news’. The article set out the Nazi regime’s view of women journalists, pigeonholing them in ‘appropriate’ roles based on their gender. Throughout the Third Reich, almost 70 per cent of women journalists worked in the realm of ‘soft’ news and rarely rose to cover foreign affairs.

The Nazis knew they had to get women on board to carry out their racist agenda, and they recruited women journalists to function as a direct channel between the state and the private realm of women and the home. The Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, said that ‘the best propaganda is that which works invisibly, penetrates the whole of life without [audiences] having any knowledge of the propagandistic initiative’ (75).

In order for women to remain in a pacified state of nonchalance towards wartime violence, spaces had to be created that promoted pleasure and happiness. The media complex was tasked with distracting Germans from violence. In the midst of the Battle of Stalingrad, Goebbels reiterated that the German people’s mood needed to be upheld to maintain a stable military campaign. After the loss of Stalingrad, the regime began to reduce the page numbers of magazines and newspapers as a result of shortages, but content to entertain the public was still deemed necessary.

Readers would gravitate towards the pages that women wrote, skipping political news for local, human interest, sports and entertainment sections. Women journalists were meant to ‘[provide] readers with a seemingly depoliticized realm of blissful domesticity, self-improvement, adventure, travel and escapism’ (54). In addition, photography was an integral part of a successful propaganda campaign that aimed to reflect a more peaceful, ‘objective’ reality. Photojournalists like Erika Groth-Schmachtenberger publicised serene shots of children going to school and figure skaters.

Although the Nazi press intended to provide its female readers with an upbeat version of events, women were among the first to feel Germany’s preparations for war. Magazines instructed women on how to change their household chores to ensure more resources went towards war preparation. In journals like NS Frauen-Warte, the paper promoted a ‘German’ mode of domesticity tied to German nationalism, which further perpetuated racist ideals. Hannah Koblick wrote about how women were working to create ‘proper Germans’ out of the ‘Volkdeutsche’ who lived in the border regions.

Women’s articles would put a ‘soft’ spin on Nazi imperialist ideology, highlighting the role of the home in contributing towards the creation of a new political order. Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, editor of the wartime women’s magazine Kamerad Frau, wrote pieces to provide comfort and encourage women to keep up the morale of German soldiers. She wrote about the art of letter-writing, instructing women to refrain from ‘burdening’ their men with their own worries.

Most women journalists were limited in their coverage, but some went beyond these gender norms and covered political matters. In 1932, Margret Boveri received her doctorate in Berlin and channeled her interest in foreign policy by joining the journalistic ranks. Boveri was able to wield journalistic prestige similar to that of her male colleagues. After the war she tried to distance herself from Nazism; however, her published work supported Hitler’s foreign policy. She wrote once to a colleague that she supported the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and that she approved of ‘this coup with Moscow’ so much that she was ‘almost ready to join the [Nazi] party’ (86).

Some women journalists blatantly supported Nazi ideology within their published articles, but others tried to skirt the reality that they were contributing to violence. Given that many women were pigeonholed to ‘feminine beats’, such as fashion, the home, culture and relationship advice, women journalists often attempted to claim an apolitical status after the war. Ursula von Kardorff covered the women’s section for the Nazi party paper Der Angriff, but in the post-war years she claimed that she never sold out to the Promi [Propaganda Ministry]. Kardorff later published Diary of a Nightmare: Berlin, 1942-1945, which chronicled her wartime experiences and was praised as an accurate portrayal of the Third Reich.

But can journalists like Kardorff be let off the hook for participating in the Nazi regime if all they wrote were women’s columns? Barton floats the question in her historical analysis but does not conduct a deeper investigation into whether women journalists should be held as responsible within the Nazi propaganda machine. Hannah Arendt argued that totalitarian regimes are built through countless cogs in a machine that enacts large-scale violence. Individuals carry out administrative and bureaucratic tasks, enabling violence on a greater scale. Adolf Eichmann perceived himself to be fulfilling mundane, bureaucratic orders laid out by the Nazi regime. Women journalists fell under a similar trap of participating in the violence of the regime, but to them their articles seemed distant from Hitler’s actions. Arendt would likely argue that their writing was imbued with violence in its critical role of distracting minds from reality.

Propaganda, even if it simply discusses fashion trends and relationship advice, is an integral part of a totalitarian regime. The question stands – can it be ethical to alleviate suffering in a totalitarian regime by providing the masses with entertainment or are you sedating the public from rising up? Barton’s Rewriting the Reich: Women Journalists in the Nazi and Post-War Press illuminates the historical role women journalists have played in permitting the actions of totalitarian regimes.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Debby Hudson on Unsplash