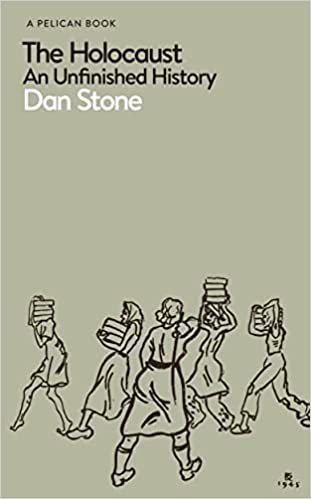

In The Holocaust: An Unfinished History, Dan Stone examines aspects of the Holocaust – from its position in relation to other twentieth-century genocides to killings perpetrated outside of concentration camps – that have arguably been overlooked in the histories and memorialisations with which we are familiar. Stone’s emphasis on the need for continued interrogation of the Holocaust’s complex realities provides a valuable lesson for our own era of polarisation and overlapping crises, writes Jack Palmer.

The Holocaust: An Unfinished History. Dan Stone. Pelican Books. 2023.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

What does it mean to write an ‘unfinished history’? This question reverberates across the pages of Dan Stone’s new book, published as part of the rejuvenated Pelican imprint whose aim is to assemble and render accessible the best of academic argumentation for a public audience. An eminent historian and the director of the Holocaust Research Institute at Royal Holloway, there are few better placed than Stone to do this difficult work in the case of the event of the Holocaust, its antecedents and afterlife.

What does it mean to write an ‘unfinished history’? This question reverberates across the pages of Dan Stone’s new book, published as part of the rejuvenated Pelican imprint whose aim is to assemble and render accessible the best of academic argumentation for a public audience. An eminent historian and the director of the Holocaust Research Institute at Royal Holloway, there are few better placed than Stone to do this difficult work in the case of the event of the Holocaust, its antecedents and afterlife.

The most straightforward meaning of an ‘unfinished history’ of the Holocaust pertains to the fact that there are significant dimensions of the event of the Holocaust which remain little known. Among the most powerfully described in the book are the astonishingly inhuman conditions in Transnistria, ‘far removed from what, in the English-speaking world, we think of as the Holocaust’, where in the winter of 1941-2, thousands of Jews were abandoned to die from disease and exposure in animal barns and pigsties (172, 193). Stone also challenges still-pervasive misunderstandings, such as the image of the Holocaust as an ‘industrial genocide’. A fascinating passage (201-2) outlines the role that the ‘Auschwitz Album’, depicting the 1944 arrival of Hungarian Jews at Auschwitz-Birkenau, have played in the sedimentation of this image in public understanding.

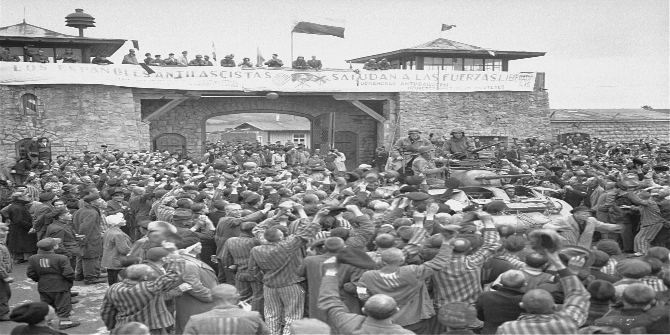

At some 300 pages, The Holocaust: An Unfinished History falls short of the length of previous synthetic histories, which often sprawl over multiple volumes. These include canonical works by figures like Raul Hilberg and Saul Friedlander, and the latter’s ‘integrated’ approach is clearly a model of influence here. Stone mobilises a formidable command of Holocaust scholarship in an invitational work for the uninitiated rather than a totalising account. The book also showcases major research works that Stone has himself contributed. The first three chapters in the book draw on his work on Nazi ideology, the politics of fascism and race science. The sixth chapter outlines the specificity of the Nazi camp system and the Reinhard Vernichtungslager, setting it within his recent global history of concentration camps. The seventh chapter covers themes from his recent work on the ‘liberation’ of the Nazi camps in 1945 (the Holocaust did not simply ‘end’ at this moment, we are shown), and previews his forthcoming account of the desperate searches for news of the millions uprooted as they unfolded in camps populated by those displaced in death marches and deportations. The book is also marked throughout by Stone’s even-handed and sophisticated appreciation of historiographical debates in Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

At a time, when Historikerstreit arguments have resurfaced, and governments within Europe have sought effectively to criminalise scholarship which problematises mythologies of national suffering and martyrdom, The Holocaust: An Unfinished History provides an important illustration of the event’s pan-European context. Though very much led by the Nazis, Stone argues that the Holocaust ought to be regarded as ‘a continent-wide crime’, the title of the book’s fifth chapter. The Holocaust, in this sense, appears a mosaic of genocidal projects as national governments from Norway to Croatia sought to remake their populations along lines of ethnic and cultural purity. Moreover, the history of the Holocaust is emphasised as a global history, playing out in the colonial administrations of North Africa and in exile communities from Bolivia to the Phillipines.

The Holocaust is ‘unfinished history’, too, because of complex processes of memorialisation. Holocaust memory is the standalone theme of chapter 8, but Stone grapples throughout the book with what Robin Wagner-Pacifici has termed the ‘ongoingness of the event’. ‘The Holocaust’, as Stone summarises, ‘names a transnational crime committed in Nazi-occupied Europe by the Third Reich and its allies, whose after-effects are felt to this day in the spheres of politics and culture in many, often unexpected ways’ (267 emphasis added). These after-effects have unfolded in the institutionalisation of international criminal law. They shadowed the postwar politics of decolonisation and the Cold War, and haunt the contemporary Middle East. The unfinished history of the Holocaust structures the progressive language of global normativity whilst also appearing, in profoundly paradoxical ways, in apocalyptic fantasies of ‘the great replacement’ and ‘white genocide’. Amidst these after-effects, the mobilisation of Holocaust memory in the Russian invasion of Ukraine stands out, and chapter 4 of Stone’s book, which sets the Holocaust in the context of the Nazi war of annihilation, is a timely reminder of the radicalising effect of military occupation.

With these contemporary examples, ‘unfinished history’ takes on another meaning, akin to what the philosopher, H.G. Gadamer, termed effective history. History is, by definition, unfinished because it is written within distinct socio-cultural horizons from which the past is viewed in ways that may not have been possible before. Why, then, a history of the Holocaust now?

Stone answers with a warning. Whilst he is very clear about the specificity of Nazi ideology and the centrality of anti-Semitism therein, he nevertheless claims that Nazism ‘drew on reserves of affect which can be found in all societies in crisis’ (300). The Holocaust was an ‘organized transgression’ (68). This is illustrated with an extraordinary passage quoted from the French journalist, Jacqueline Mesnil-Amar shortly after the war:

It’s easy to appear indignant in the face of the crimes committed by these brutes, to exclaim that ‘these people are monsters’, and then go back home for a peaceful dinner and sleep with a clear conscience. For there to have been that many monsters, there must have been something unusually propitious for the gestation and growth of monsters, something complex which exists at some level in all of us, and in which each and every one played a part. Across the entire German nation Nazism produced a strange desire to destroy their world and, in a sort of collective intoxication, bordering on madness, to allow another to arise in its place, a world of death, a dark, repugnant bloody and sadistic medieval world (299-300)

At our own time of overlapping crises, the history of the Holocaust must remain unfinished because, Stone argues, it is open to serious question ‘whether we have done enough to resist apocalyptic visions and movements when they reoccur, as they already have done and will continue to do in a world convulsed by global warming, mass migration of climate and war refugees, pandemics and xenophobia, and shaped, more and more often, by a perverse delight in the apocalypse that is to come’ (302-3). The history of the Holocaust serves, today, as a reminder of the destructive potential latent in ‘the deep psychology of modernity’, a problem ‘more pressing now than at any time since historians began to write about the Holocaust at the end of the Second World War’ (xxxi-xxxii).

The hermeneutic point that we remember over and over again as conditions change is also a moral one. Underpinned by the conviction that ‘we have failed unflinchingly to face the terrible reality of the Holocaust’ (302), Stone draws extensively on first-person testimonies and vivid recounting of the excessive cruelty that unfolded within the varied spaces of the Holocaust. They are almost unbearable to read, and yet we must read them. The Holocaust: An Unfinished History manages to be both straightforwardly accessible and profoundly difficult. This is as it should be.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Main Image Credit: The Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial or ‘Nameless Library’, Vienna, designed by Rachel Whiteread via Brian Dooley on Flickr.