In Activist Affordances: How Disabled People Improvise More Habitable Worlds, Arseli Dokumacı argues that in the adaptive ways they improvise everyday tasks, disabled people demonstrate how all people can create a more habitable planet. Connecting ideas from the fields of ethnography, psychology, disability studies and performance studies, Dokumacı’s original work challenges normative, ableist conceptions of activism and environmental protection, writes Kostadin Karavasilev.

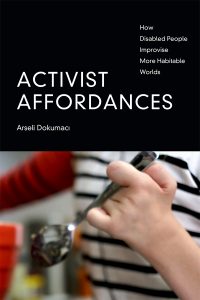

Activist Affordances: How Disabled People Improvise More Habitable Worlds. Arseli Dokumacı. Duke University Press. 2023.

In her book Activist Affordances: How Disabled People Improvise More Habitable Worlds, Arseli Dokumacı presents a theory, and critical vocabulary that foreground how people with disabilities manage to create more liveable worlds through their everyday actions. The title highlights disability, but this work seamlessly reaches beyond this realm. Activist Affordances provides ways of thinking and acting that surpass the individual to speculate how everyday actions can create a more habitable planet.

In her book Activist Affordances: How Disabled People Improvise More Habitable Worlds, Arseli Dokumacı presents a theory, and critical vocabulary that foreground how people with disabilities manage to create more liveable worlds through their everyday actions. The title highlights disability, but this work seamlessly reaches beyond this realm. Activist Affordances provides ways of thinking and acting that surpass the individual to speculate how everyday actions can create a more habitable planet.

Activist Affordances provides ways of thinking and acting that surpass the individual to speculate how everyday actions can create a more habitable planet.

Including her own experiences of living with “chronic diseases that damage [her] joints, causing pain and gradual disablement” (1), Dokumacı investigates invisible impairments – primarily inflammatory arthritis, but also blindness, cancer, depression, thyroid disease, and chronic pain – in Western Turkey and Quebec, Canada. She takes an ecological approach and grounds her ideas in twelve years of ethnographic research, filming aspects of participants’ daily lives and activities as well as asking people living with disabilities (and, when possible, those close to them) about their experiences. She asks how people with disabilities find ways to interact with and inhabit environments which assume certain bodily and mental abilities and normative ways of engaging with the world. By asking these questions, Dokumacı foregrounds what the adaptive behaviours of disabled people can teach us about how society in general could enable a more habitable future for all.

Affordance encompasses all organisms and suggests that each organism and the environment they inhabit are interrelated.

The book is divided into two parts. In the first part, Dokumacı provides a comprehensive overview of the theory of affordances from the field of psychology – James J. Gibson’s ecological approach to perception. Affordance encompasses all organisms and suggests that each organism and the environment they inhabit are interrelated. Given that the body of each organism enables it to perceive and act in idiosyncratic ways, the environment and the things that populate it provide organisms with information on the possible ways that they can engage with a given object. Hence, perception and action are shaped via interactions with the environment. Affordances are embodied in the materiality of objects and prompt possible actions that organisms learn to perceive.

Thinking about affordances through disability theory, Dokumacı argues that Gibson worked under the assumption that all humans are able-bodied and hence, when engaging with the environment, the same affordances for action are available. A comb, for instance, does not provide the same affordance to a person with arthritis affecting their arms compared to someone with flexible and painless limbs. One of Dokumacı’s participants with arthritis found it less painful to bend her head to her shoulder while placing the comb in her hair with one hand and drawing the comb through her hair with her other hand (for a visual illustration, see end of this article).

Dokumacı shows that in an environment where the norm is an able body, the readily available affordances diminish for people with disabilities.

Through such examples, Dokumacı shows that in an environment where the norm is an able body, the readily available affordances diminish for people with disabilities. Thus, the possible interactions with the environment become less – the environment ‘shrinks’. She highlights the theoretical contribution of her concept of “shrinkage” as a way to avoid the environmental determinism present in social models of disability that focus on access. Arguing that changes in ailments often occur and thus the possibilities for interacting with one’s environment also change, the author argues that the concept of shrinkage provides a more nuanced way of thinking about such fluctuations than access does. Shrinkage provides a vocabulary that goes beyond ideas that a more accessible environment would provide people with more affordances. Foregrounding embodied experiences, Dokumacı argues that “[e]ven the most accessible environments can still be experienced as shrinking when one falls chronically ill (rather than periodically so), or when the body suffering from a chronic disease progressively degenerates” (69). Dokumacı understands shrinking via what she calls the “habitus of ableism.” This is a way of engaging with the world that children are exposed to from a young age and that perpetuates specific ways of perceiving, thinking, and acting. It establishes normative ways of engaging with one’s environment based on assumptions of able-bodiedness; hence, it renders certain (ableist) affordances more readily perceivable than others.

In part two of the book, Dokumacı elaborates her theory. Drawing on ideas from performance studies, she likens the shrunken affordances that her participants experience to those of actors on a stage. Actors (re)create the world of a play by improvising with their bodies and limited décor. Likewise, in a shrunken environment people with disabilities must find affordances that go beyond the readily available ones offered through the dominant habitus. To make their environment more liveable, people with disabilities must be creative and improvise new affordances using only their bodies and, possibly, objects around them.

Dokumacı calls such affordances “activist affordances” as she wants to highlight their creative capacity to bring about not readily perceivable affordances and challenge extant, ableist ideas of activism. She argues that everyday actions – such as peeling a lid off a small bottle with one’s teeth due to arthritic arm-pain – possess the ability to re-imagine our engagement with our environment and make it more habitable. On a planetary level, Dokumacı speculates on how people with disabilities’ activist affordances could encourage new ways of inhabiting a planet shrinking under exploitation. Activist affordances do not require the production of new artefacts but only rely on one’s body and what is already available. Hence, Dokumacı suggests activist affordances could “be a way of addressing the pressing question of how to negotiate a shrinking planet with diminishing resources, or provide a starting point for doing so” (252).

Dokumacı calls such affordances “activist affordances” as she wants to highlight their creative capacity to bring about not readily perceivable affordances and challenge extant, ableist ideas of activism.

As any work suggesting theoretical interventions, Activist Affordances elucidates certain aspects of a phenomenon but leaves out others. Although it acknowledges the domination of the habitus of ableism, the strong focus on action shifts away from power relations inherent in gender, class, and race, which affect relations to the environment for people with disabilities. Even though Dokumacı mentions that her participants are variously affected by their ailments due to socio-economic and political differences, these remain at the back of the mise-en-scène of the analyses. In parts of her interpretation of personal narratives (especially chapter nine) the idea that living with disability “gets better” with time surfaces, as with time people adjust to living with a ‘non-normative’ body. Even though Dokumacı points out that grief related to someone’s disability could still be felt even after many years of living with it, the lack of broader contextualisation disregards privilege and power structures among people with disabilities that raise the question, for whom does it get better (see Jasbir Puar)? Additionally, it does not become clear in the book how people with mental health issues engage in creating affordances since no cases are specifically designated as ones of people with depression. It left me wondering how Dokumacı applied the theory and methods she elaborates on, primarily through examples of arthritis, to such cases. An aspect that other ethnographies of practice aiming to provide theories applicable beyond the phenomenon they studied – eg, Annemarie Mol’s study of atherosclerosis – have remained vague about this too.

In sum, Dokumacı provides an original perspective to doing disability studies by foregrounding embodiment, the environment, and “ordinary” actions. Activist Affordances attunes readers to individual, everyday acts that could teach us how to create more habitable futures. Such a perspective opens new spaces for scholarly and political debates on activism, disability, and the preservation of the planet.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Main Image: CURVD on Unsplash.

1 Comments