In House of the People: Parliament and the Making of Indian Democracy, Ronojoy Sen examines the workings of India’s parliament and the factors that have eroded its democracy in recent decades. Sen offers a well-researched and insightful study of India’s lower house and a caution to other nations on the dangers of losing grip on democratic protections, writes Eugene L. Wolfe.

House of the People: Parliament and the Making of Indian Democracy. Ronojoy Sen. Cambridge University Press. 2023.

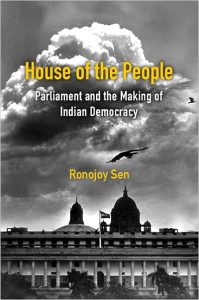

Perhaps you can judge some books by their covers. The front of Ronojoy Sen’s House of the People: Parliament and the Making of Indian Democracy features a striking photograph of a dark cloud looming over Parliament House in New Delhi. The text paints an equally threatening picture of the transformation and prospects of the institution within the building. The fate of this House is important not only for India, the world’s largest democracy and home to one of its most dynamic economies, but more broadly as popular self-rule seems in peril around the globe.

Perhaps you can judge some books by their covers. The front of Ronojoy Sen’s House of the People: Parliament and the Making of Indian Democracy features a striking photograph of a dark cloud looming over Parliament House in New Delhi. The text paints an equally threatening picture of the transformation and prospects of the institution within the building. The fate of this House is important not only for India, the world’s largest democracy and home to one of its most dynamic economies, but more broadly as popular self-rule seems in peril around the globe.

The fate of this House is important not only for India […] but more broadly as popular self-rule seems in peril around the globe

The forecast was once much sunnier. In the years immediately following independence from Britain in 1947, India surprised some pessimists by forging a robust democracy in which parliament, despite domination by the Congress party, played a central role. Then came the Emergency (1975-7), during which Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, facing legal challenges and political disorder, imprisoned many of her opponents and suspended civil liberties. In the 1977 general election, Congress was swept from power for the first time. Although it would return to office three years later, changes were afoot that would undermine both Congress and the parliament it long dominated.

The political class became more reflective of India’s diverse 1.3 billion-strong population, although members of parliament remained much older and […] predominantly male

Some of these developments were salutary. The political class became more reflective of India’s diverse 1.3 billion-strong population, although members of parliament remained much older and more predominantly male than those they represented. Elections became increasingly competitive, in part because the number of parties burgeoned; where 29 parties had contested the 1962 general election, by 2019 this total had increased to 662. And, in an era in which coalition governments became common, parliament was able to claw back some power from the executive by more fully developing its committees to improve legislative scrutiny.

However, as Sen recounts, these steps forward can be seen as but the silver lining to what was becoming a noxious political cloud. As parties proliferated in parliament – there were 36 as of 2019 – many smaller ones on the opposition benches, dissatisfied with the debate time allocated to them, sought to draw attention to themselves or the causes they held dear by disrupting legislative business. More competitive elections became increasingly expensive, as a result of which it became virtually impossible to prevail while abiding by electoral-financing laws. The pursuit of untraceable election funds fostered not only corruption scandals but also backing by parties of many deep-pocketed candidates facing criminal charges, some for very serious offenses such as murder.

The pursuit of untraceable election funds fostered not only corruption scandals but also backing by parties of many deep-pocketed candidates facing criminal charges

Although Sen devotes considerable attention to these issues, it is not clear that they have been as debilitating as he implies. While disruptions have consumed much valuable parliamentary time, they also have been a means by which opposition parties have forced the government to address major scandals, effectively enhancing parliament’s role in providing accountability. He touches on, but does not discuss in much depth, several other factors that seem at least as important in explaining parliament’s long-term decline. These include: a general shift in power from the centre to state governments; a public that strongly prioritises the provision of constituency services over legislative participation; the attenuation of political parties; a relatively low incumbent re-election rate; a committee system that does little to foster the accrual of institutional expertise; and a decline in the share of seats held by lawyers—from around 30% in 1952 to 3.5% in 2019.

Domination by the executive is a danger in any parliamentary system, but it seems a particular peril in India.

Domination by the executive is a danger in any parliamentary system, but it seems a particular peril in India. While governments occasionally have faced no-confidence votes, episodes in which prime ministers feared substantial parliamentary interference – as happened in Britain in 2019, resulting in a constitutionally-dubious Brexit-related prorogation – seem vanishingly rare. (The 1975 Emergency was precipitated by popular demonstrations and legal rulings against the head of the government, not a parliamentary challenge.) As a result, parliament’s role historically has varied to no small degree depending on the whim of the premier: Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, revered parliament, so the institution flourished; Indira Gandhi, his daughter and eventual successor, neglected and marginalised it.

Although polls consistently show strong popular support for democracy in India, in 2014 voters gave power to the Bharatiya Janata Party, which rose to prominence by organising a 1992 rally in which a Hindu mob demolished a mosque.

This, combined with the many factors that seem to have weakened parliament over the last few decades, creates a very troubling situation. Although polls consistently show strong popular support for democracy in India, in 2014 voters gave power to the Bharatiya Janata Party, which rose to prominence by organising a 1992 rally in which a Hindu mob demolished a mosque. Its leader, Narendra Modi, then Chief Minister of the state of Gujarat, was accused (but later cleared) of complicity in 2002 inter-communal riots that left over 1,000 dead. Modi appears no great fan of parliament, in which he participates as little as possible. In 2021 his government rammed repeal of an unpopular farm bill through both houses of parliament in a total of 12 minutes. This disdain for an already-weakened parliament, coupled with apparent efforts to undermine other institutions that might challenge his government’s Hindu-nationalist agenda, would seem to pose the significant threat to Indian democracy implied by the book’s cover.

Sen, a former journalist who is now a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore, has written a well-researched and thoughtful study of an institution in need of what he terms a “biography.” However, his work could be more accessible to those who do not specialise in Indian politics. One problem is that he only hints at, rather than clearly spells out, some of the important ways in which elections and political parties operate differently in India than in other countries. A brief explanation of some of these differences would have made it easier for readers unfamiliar with Indian politics to understand why, for example, parliament has a superabundance of political parties despite an electoral system thought to encourage party consolidation, why criminals so frequently win election, and why lawmakers regularly switch parties. Similarly, while Sen shows a command of the literature on Indian politics, he sometimes seems to assume that readers are equally well informed, using terms like the “third electoral system” without fully explaining them. Moreover, while abbreviations, many seemingly unique to the Indian context, are used frequently, they are not indexed or listed separately. These relatively minor concerns notwithstanding, House of the People provides valuable insight into the workings and evolution of an institution at the centre of what may prove to be India’s coming political storm.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Talukdar David on Shutterstock.