As we approach Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday 2023, Alex Mayhew, Assistant Professor in Modern European History at LSE, and an expert on the history of the First World War, shares a reading list of five books that explore the commemoration of war in Britain and beyond.

As we near Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday, the commemorative ceremonies have become a cause for debate once more. This time, however, the discussions do not focus solely on well-worn questions about their meaning, nor on the political messages that might underpin wearing poppies or the two-minutes silence. They emerge from divergent responses to a conflict of a much more immediate nature. Rishi Sunak feels that any demonstrations would be “provocative and disrespectful”. In contrast, whilst protests can undoubtedly create difficulties, several historians have noted that demonstrations demanding a ceasefire – ultimately, cries for peace – “can be seen as closely related to some of the most established historical traditions of the day. An Armistice is literally a ceasefire – albeit of a complex variety.” It would appear that other organisations, from the Western Front Association to the Metropolitan Police, agree – or, at least, believe in privileging freedom of speech and the right to protest.

Several historians have noted that demonstrations demanding a ceasefire – ultimately, cries for peace – ‘can be seen as closely related to some of the most established historical traditions of the day. An Armistice is literally a ceasefire – albeit of a complex variety.’

We should remember that practices of commemoration are invented. Illustratively, it was only after the fiftieth anniversaries of the D-Day landings, V-E Day, and V-J Day in 1994 and 1995 that the Royal British Legion lobbied to reintroduce the two minutes silence on Armistice Day itself. Whilst they might appear to symbolise continuity, these practices have changed to mirror the needs and wants of different generations and communities in the years since the guns fell silent in Belgium and France on 11 November 1918. Therefore, they are inherently, and regularly, contested. For this reason, then, there is perhaps no more apt a vehicle for confronting and considering the terrors of war today. At the same time, we should be suspicious of anyone that imposes a single, static, meaning on these events.

Whilst they might appear to symbolise continuity, these practices [of commemoration] have changed to mirror the needs and wants of different generations and communities in the years since the guns fell silent in Belgium and France on 11 November 1918.

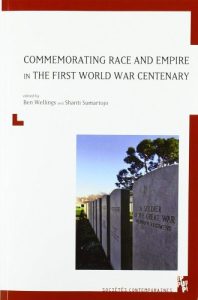

The Great War and the current conflict between Israel and Gaza are related in other ways. Beyond the historical parallels one might draw (including the consequences of 1914-1918, its imperial dimensions, and the geo-political fall-out) there are threads of a more human kind. Palestine was a theatre of war then, too, and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) maintains several sites in the region, including two cemeteries in the Palestinian territory. One of these, the Gaza War Cemetery, is the final resting place of individuals from many places and backgrounds. The majority are British, but one can also find the graves of Ottoman, Indian, Australian, Polish, and Canadian troops. Significantly, as is the case with many CWGC graveyards, it is also maintained by local staff. Indeed, this sight of memory has been diligently (and beautifully) cared for by Ibrahim Jaradah’s family for one hundred years. Yet, it is now he, his relatives, and countless others, that are confronting the violence of modern warfare.

The Gaza War Cemetery, is the final resting place of individuals from many places and backgrounds. The majority are British, but one can also find the graves of Ottoman, Indian, Australian, Polish, and Canadian troops.

Below, readers will find a selection of five books to enrich their understanding of how the First World War has been commemorated over the past century, in Britain and internationally.

1. Adrian Gregory, The Silence of Memory: Armistice Day, 1919-1946 (Bloomsbury, 1994)

1. Adrian Gregory, The Silence of Memory: Armistice Day, 1919-1946 (Bloomsbury, 1994)

Gregory’s monograph might be nearly thirty years old, but it provides a detailed, compelling, and at times moving, account of how the British made sense of the traumas of the Great War. His analysis of the public ceremonies that took place in and around Armistice Day on 11 November uncovers how these reflected (and mediated between) the wishes of veterans and the bereaved, were often “multi-vocal”, and inflected the memory of the conflict itself. Beyond this, Gregory’s narrative exhibits the ways in which commemoration was altered and morphed as history continued to play itself out. New realities – especially the shadow of war in the 1930s – changed perceptions of the past and the purpose of the rituals. For this reason, the global conflict in 1939-45 fundamentally reshaped, and eroded, the ideas and beliefs that fed the practice of commemoration in the interwar years. Armistice Day was suspended during the war and in its aftermath Remembrance Sunday became the focus of events.

2. Jay Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History (Cambridge University Press, 1995)

2. Jay Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History (Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning is a classic text on the history of the Great War and cultural history more generally. In this book, Jay Winter interrogates mourning during and after the war. Unlike The Silence of Memory, this takes a pan-European (and, at times, Australian) perspective, and shows what a transnational lens can offer to our understanding of a phenomena – namely grief – that defies national categorisation. Though, as Winter shows, it does vary over space and time, whether it is expressed publicly or in private. The psychological adjustments that were necessitated by the war’s traumas fed culture after 1918, but this often drew on traditional, frequently pre-war, ideas and norms. Presciently, at least this coming weekend, Winter examines how war memorials became a “foci of the rituals, rhetoric, and ceremonies of bereavement” (78).

3. Dan Todman, The Great War: Myth and Memory (Bloomsbury, 2005)

3. Dan Todman, The Great War: Myth and Memory (Bloomsbury, 2005)

Commemoration, and mourning, are common experiences across borders. The cultural afterlife of the First World War is also one that spreads beyond individual nations. For example, trenches, No Man’s Land, or going “over the top” have become shorthand and metaphor in many English-speaking countries. They are also tropes we fall back on to make sense of contemporary conflict. One only need think about how frequently pictures from the frontlines of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are compared to scenes from the Western Front. Nevertheless, historical memory is often peculiar to one country’s construction of its own past. Britain’s memory of the Great War is particular and distinctive, often sitting at odds with scholars’ interpretations of its history. Dan Todman’s book explains how this came to be by focusing on the “functions” of myths (namely those of mud, death, donkeys, futility, and poets). Drawing on literature, television, films, and much more besides, he reveals how public perceptions – like commemoration – are not static. In fact, Britain’s memory of the Great War has evolved, reflecting the ever-changing priorities of a society that has itself transformed both culturally and demographically.

4. Bart Ziino (ed.), Remembering the First World War (Routledge, 2015)

4. Bart Ziino (ed.), Remembering the First World War (Routledge, 2015)

Of course, the First World War does not only form a part of collective memory in Britain. Memory is also shaped by more than just practices of commemoration. To truly understand the diversity of ways in which 1914-1918 has been memorialised requires a more holistic approach. Bart Ziino’s edited volume, Remembering the First World War draws together the work of a variety of leading international scholars to understand why interest in the First World War has grown in recent years. To do so, it focuses the significance of family history, practices of remembrance, and the reincorporation of the war into commemorative narratives of several countries. Karen Petrone’s chapter on Russian celebrations during the centenary of the war, Vedica Kant’s essay on the memory of Gallipoli in Turkey, and Keith Jeffrey on the hazards of commemoration in Ireland reveal just how inherently political the commemoration of war is, even when that conflict has now passed into historical memory.

5. Ben Willings, Shanti Sumartojo, and Matthew Graves (eds.), Commemorating Race and Empire in The First Word War Centenary (Liverpool University Press / Provence University Press, 2018)

5. Ben Willings, Shanti Sumartojo, and Matthew Graves (eds.), Commemorating Race and Empire in The First Word War Centenary (Liverpool University Press / Provence University Press, 2018)

Recent historiographical shifts have encouraged historians to study the Great War through new temporal and spatial lenses. In many places, and in many minds, the war did not end on the 11 November 1918. Furthermore, there is a reason that the dead of so many nationalities lie in Gaza War Cemetery. This was an imperial conflict and our understanding of the First World War’s commemoration – not just its course and consequences – should be approached through a global lens. This edited volume provides a welcome, and important, contribution to our understanding of the global First World War, and its afterlives. The chapters contained in it investigate the commemoration (and memory) of the war across the world and amongst a range of different communities. Whilst every contribution is worth reading, I was particularly struck by Laurence van Ypersele’s and Enika Ngongo’s discussion of the Belgian Congo, Elizabeth Rechinewski’s analysis of the role of Black African troops, and Dónal Hassett’s fascinating research into memory and war memorials in post-colonial Algeria.

Note: This reading list gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image: Headstones in the Gaza War Cemetery. Credit: Joe Catron on Flickr.