In The Unequal Effects of Globalization, Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg looks at globalisation’s effect on inequality, emphasising regional frictions, rising corporate profits and multilateralism as focal points and arguing for new, “place-based” policies in response. Though Goldberg provides a sharp analysis of global trade, Ivan Radanović questions whether her proposals can effectively tackle critical issues from poverty to climate change.

The Unequal Effects of Globalization. Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg (with Greg Larson). MIT Press. 2023.

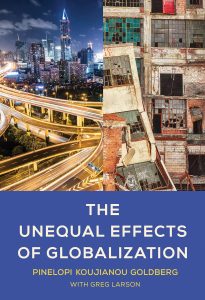

Glancing at the megalopolis on the left and abandoned building on the right side оf the book cover, I made an assumption about its narration: from the 1980s onwards, trade unions and states were blamed for rising inflation and unemployment. Fiscal cuts, deregulation and privatisation replaced public interest with private ones: maximising profit, firms outsourcing manufacture. What at first went alongside and later instead of promised economic efficiency was wealth accumulation at the top and the surge of corporate profits. As workers’ real wages fell behind, inequality grew.

Glancing at the megalopolis on the left and abandoned building on the right side оf the book cover, I made an assumption about its narration: from the 1980s onwards, trade unions and states were blamed for rising inflation and unemployment. Fiscal cuts, deregulation and privatisation replaced public interest with private ones: maximising profit, firms outsourcing manufacture. What at first went alongside and later instead of promised economic efficiency was wealth accumulation at the top and the surge of corporate profits. As workers’ real wages fell behind, inequality grew.

As an academic specialising in applied microeconomics, Goldberg investigates globalisation’s many dimensions and complex interactions, from early trade globalisation to the rise of China, from western deindustrialisation to its effects on global poverty, inequality, labour markets and firm dynamics.

I was wrong. As an academic specialising in applied microeconomics, Goldberg investigates globalisation’s many dimensions and complex interactions, from early trade globalisation to the rise of China, from western deindustrialisation to its effects on global poverty, inequality, labour markets and firm dynamics. The book does concur with my assumption, but it engages with it in a more unique way.

According to Goldberg, the increase in global trade is due to developing countries’ entry into international trade since the 1990s.

Starting from an economic definition of globalisation, the author emphasises the lowest ever levels of (measurable) trade barriers and, consequently, the highest global trade volumes. According to Goldberg, the increase in global trade is due to developing countries’ entry into international trade since the 1990s. It is inseparable from global value chains (GVCs), complex production processes that – from raw material to product design – take place in different countries. The author argues that “the increasing importance of developing countries in world trade reflects their participation in GVCs” (6). That is the creation story of hyperglobalisation. For Goldberg, it is observable by the total export share in global GDP: “being fairly constant in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it began rising after World War II and accelerated dramatically in the 1990s and early 2000s.” That is exactly when the World Trade Organization (WTO) was founded, and many multilateral trade agreements were signed. The key was trade policy.

But not everyone agreed. Some economists, including Land Pritchett and Andrew Rose, contended the growth was not due to trade, but the development of technology and fall of transportation costs. Goldberg rejects this argument, pointing out that technology was developing long before. Hyperglobalisation started because trade policies encouraged multilateralism; “Trade policy – especially the creation of a predictably stable global trading environment – was at least as important as technological development“ (17).

Since international trade is largely about distributional gains and losses, the key question is whether the recent tensions and protectionism – such as Brexit, Trumpism and American trade war with China, to name the most visible examples – are just blips in irreversible globalisation, or signs of deglobalisation.

This is important because international trade is a perennial source of discontent within globalisation, and exploring its causes is the primary focus of this book. Since international trade is largely about distributional gains and losses, the key question is whether the recent tensions and protectionism – such as Brexit, Trumpism and American trade war with China, to name the most visible examples – are just blips in irreversible globalisation, or signs of deglobalisation. It depends on policy choices.

In the second half of the book, Goldberg turns to inequality and differentiates it into global inequality and intra-country inequality. From the global perspective, the author points out two major contributions. The famous “elephant curve“ developed by Lakner and Milanovic (2016, p. 31) showed very high income growth rates for world’s poorer groups from 1980 to 2013. This primary observation is accompanied, however, by the almost stagnant income of the middle classes in developed countries (the bottom of elephant’s trunk) and high rates of growth for the world’s top one percent (its top). But how high? The answer came five years later, when Thomas Piketty and colleagues concluded (2018, p. 13) this elite group captured 27 per cent of global income growth between 1980 and 2016.

Analysing internal inequalities, Goldberg states that globalisation affects people twofold: as workers and as consumers.

This still does not refute that income rose for all groups, remarkably reducing poverty. But what about inequalities? Goldberg further investigates whether there is a trade-off between global inequality and within-country inequality. Analysing internal inequalities, Goldberg states that globalisation affects people twofold: as workers and as consumers. These effects are well-researched in developed countries like the USA, where trade liberalisation with China since the late 1990s brought multi-million job losses. Citing scholars such as David Autor, Gordon Hanson, David Dorn, and Kaveh Majlesi, Goldberg finds this trend disturbing for ordinary citizens. One could suppose that although jobs were lost, this was compensated by lower consumer prices which benefitted everyone. However, that’s exactly what did not happen in the US. Firms took almost all benefits, which meant that greater trade did not reduce consumer inequality. Crucially, even if it had, it would not compensate for the negative effects on the labour market. Therefore, as Deaton and Case argued, it is no surprise that the millions of jobless, low-educated Americans whose quality of life and even life expectancy is in decline oppose globalisation.

But the advent of trade with China cannot fully explain this issue. There are severe labour mobility frictions that prevent people from moving to another town, county or state to find a better job. That is an American trademark since, as Goldberg suggests, “Europe normalized their trade with China much earlier and in a much more gradual manner“ (55). In other words – a policy problem needs policy solution.

[Trade’s] adverse effects, such as the exceptionally high benefit claimed by the top one percent and the stagnation of the middle class in the Global North, cannot be attributed to trade per se, but to a lack of policies that absorb disruptions.

Goldberg is an optimist: poverty has fallen throughout the world, pulling hundreds of millions out of extreme poverty (defined living on or below 1.9 international dollars per day) particularly in countries that plugged themselves into GVCs. Trade, therefore, played a positive role. This implies that its adverse effects, such as the exceptionally high benefit claimed by the top one percent and the stagnation of the middle class in the Global North, cannot be attributed to trade per se, but to a lack of policies that absorb disruptions. More than tariffs, this includes workforce development, social protection, corporate taxation, and other policies that protect people from unregulated market forces. This is where real improvement lies, with broad and sincere international cooperation.

[Goldberg] seems to suggest that the global economy is functional; it just requires a little fix here and there in order to fight climate change as one of the ‘challenges of tomorrow’

The author writes from a “middle position“, so neutral that there is no mention of the word “capitalism“ in the whole book. Goldberg is aware of inequalities, but still emphasises dynamic poverty reduction. She seems to suggest that the global economy is functional; it just requires a little fix here and there in order to fight climate change as one of the “challenges of tomorrow“ (90). (This might be ok if climate change was a challenge of tomorrow – but it is not.) The evidence has been mounting for decades: polar ice caps melting, rising sea levels, deforestation and biodiversity loss, desertification and soil depletion, plastic pollution and fishery collapse. Our world is dying today, and the consequences are fierce and unequal. While the common poverty-reduction argument based on $1.9 a day is severely disputed, economic equality is highly correlated with desired outcomes including higher longevity rates, political participation, better mental health and life satisfaction.

This position, which one could view as reinforcing a profit-centred status quo from the former chief economist of the World Bank does not surprise. Her monograph has certain strong points, namely its neutral overview, its in-depth analysis of trade and and its insight into new, relevant literature. But writing about globalisation today demands more. To confirm that a problem exists is not enough. We need immediate action.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Donatas Dabravolskas on Shutterstock.

1 Comments