In The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life, Theresa May examines several “abuses of power” by politicians and civil servants involved in policy, and advocates for a shift from careerism to public service is needed to achieve better governance. In Chris Featherstone‘s view, May’s selective case studies and weak defence of her role in controversial events like the Windrush scandal will do little either to forge a new model of British politics or rehabilitate her reputation.

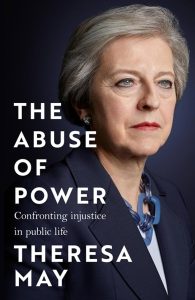

The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life. Theresa May. Headline. 2023.

This is not your typical political memoir. The reader is assured of this by a glance at the dust jacket before even opening The Abuse of Power. In recent tradition, books by former Prime Ministers typically take the form of an attempt to correct the narrative of their time behind the famous black door (David Cameron’s For the Record), or to explain their route to the top job in UK politics (Tony Blair’s A Journey). Taking an alternative tack, Theresa May scrutinises a range of cases of what she calls “abuses of power” by politicians and civil servants involved in policy, analysing the reasons behind them. Yet, despite this ostensibly different approach, The Abuse of Power reveals itself as an attempt to rehabilitate May’s reputation after her acrimonious exit from Downing Street in 2019.

This is not your typical political memoir. The reader is assured of this by a glance at the dust jacket before even opening The Abuse of Power. In recent tradition, books by former Prime Ministers typically take the form of an attempt to correct the narrative of their time behind the famous black door (David Cameron’s For the Record), or to explain their route to the top job in UK politics (Tony Blair’s A Journey). Taking an alternative tack, Theresa May scrutinises a range of cases of what she calls “abuses of power” by politicians and civil servants involved in policy, analysing the reasons behind them. Yet, despite this ostensibly different approach, The Abuse of Power reveals itself as an attempt to rehabilitate May’s reputation after her acrimonious exit from Downing Street in 2019.

The Abuse of Power reveals itself as an attempt to rehabilitate May’s reputation after her acrimonious exit from Downing Street in 2019.

The book examines examples of “injustice in public life”, highlighting the flaws in how government has approached and dealt with these issues. Examining cases ranging from the Salisbury Poisonings and the Hillsborough disaster to Brexit and the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, May highlights two factors. Firstly, she argues that it is the natural disposition of many in the public sector to place protecting the public sector ahead of the interests of those they serve. Secondly, she observes the growth of careerism and popularity-seeking amongst politicians, and the prioritisation of this over “the job they are there to do”.

May argues for the necessity of a deep attitudinal change in those in public life, especially from civil servants and politicians.

May’s proposed solution to these pervasive flaws in British public life is “service”, a theme that runs throughout her account of her own political career. As such, May argues for the necessity of a deep attitudinal change in those in public life, especially from civil servants and politicians. Her calls for greater diversity in those recruited to the civil service and a wider selection of candidates to stand in elections are well-intentioned, but unsupported with recommendations for how this can be achieved.

At first glance, her proposal that working for the broad public good could prevent many of the scandals she analyses appears somewhat convincing.

At first glance, her proposal that working for the broad public good could prevent many of the scandals she analyses appears somewhat convincing. The analysis used to form this argument is engaging, especially in those cases where May has personal knowledge, such as the Grenfell Tower tragedy (when external cladding on a tower-block caught fire, killing 72 people) or bullying and sexual harassment in Westminster. Yet, this reveals an underlying theme that accompanies the focus on “service”: May’s attention to governance rather than politics.

This partiality is reflected in May’s scepticism of politicians’ relationship with the media. In a chapter on social media, May characterises politicians’ use of social media as a superficial means of humanising them by showing the coffee cup they use or their typical breakfast. Despite raising important concerns on regulating the use of social media (whilst in Downing Street May initiated a government review of social media regulation, attacking the “vile” messages sent to female MPs), her simplistic and patronising framing of the use of social media in communication between politicians and the electorate is out of touch, and detracts from her argument.

May’s focus on effectively serving the public is coupled with a disregard for the politics of government, the importance of persuading people why policies are effective.

May’s media scepticism continues in her view of what characteristics are desirable in leaders. She condemns both short-term headline-seeking and the media focus that means if a leader does not speak to the media they are “written off.” These reactions against contemporary media and political communication methods are almost quaint, demonstrating wishful thinking for a bygone era of politics. May’s focus on effectively serving the public is coupled with a disregard for the politics of government, the importance of persuading people why policies are effective.

The Brexit chapter in particular highlights this inattention to the importance of persuading people – politicians and voters alike – of her approach. May accuses some MPs, including former Speaker John Bercow, of abusing their power by voting in their own, rather than the “national” interest when debating her Brexit deal. May’s compromise position – that the whole of the UK would remain in a de-facto customs union with the rest of the EU, and the UK and EU would have to agree to the UK’s withdrawal from this de-facto arrangement – received little support from either the remain or from the “hard Brexit” wings of her own party, or from opposition parties.

What stands out is May’s lack of engagement with the other views in the Brexit debates, giving insight into her difficulties building unity in the Conservative party during the Brexit process.

What stands out is May’s lack of engagement with the other views in the Brexit debates, giving insight into her difficulties building unity in the Conservative party during the Brexit process. Conspicuously absent is an explanation of how this judgement of “national interest” was made, other than this simply being May’s opinion. There is a ring of the internal-external attribution problem in her assessment, wherein she attributes her own actions to a personal conviction to pursue a “compromise” position in the national interest, and others’ actions to political machinations for personal gain. The chapter unintentionally highlights a root of the May government’s difficulties in persuading MPs and the public of the efficacy of their approach to Brexit.

The book’s highly selective approach to the cases analysed is epitomised in the chapter on the Hillsborough disaster, when 97 Liverpool football fans died in a crush, the UK’s worst sporting disaster. May confesses that when the tragedy occurred, she believed the “propaganda” put out by the police, politicians, and the media. May was by no means alone in this acceptance of the official line, yet, of the three groups she identifies in promulgating this lie, it is the police who come in for the major share of her analytical ire. As a former Conservative Home Secretary and Prime Minister, and current Conservative backbench MP, the inattention to the torrid relationship between Conservative politicians and Liverpool as a city as well as to the Hillsborough tragedy is a stark omission. Except for a couple of sentences on the role of politicians, the chapter largely diminishes their role in the framing of the tragedy in public discourse. Notably, almost all references are to “politicians”, intentionally skating over the (Conservative) party which they represented.

[May] fails to substantively support her claim and convince readers how Windrush is markedly different from the other abuses she examines.

Similarly, the explanation of the Windrush scandal, in which she was embroiled, is short and historically focused. May’s defence of the fiasco (which saw hundreds of Caribbean immigrants wrongfully issued with deportation notices) is that whilst other abuses of power she examines were to defend an institution, the Windrush case was in defence of a policy. She fails to substantively support her claim and convince readers how Windrush is markedly different from the other abuses she examines. May accuses the US of an abuse of power in the withdrawal from Afghanistan, and yet this would surely be defended by the Biden administration as the enaction and defence of their policy of troop withdrawal. Similarly, May’s defence of the use of the term “hostile environment” in her controversial immigration policy lacks depth. She suggests that when the term was proposed, it clearly referred to people who were in the UK illegally, implying that the controversy stems from its misinterpretation. This assumes it was merely the name of the policy, rather than the contested and controversial views that it was built on, with which critics disagreed.

The underlying message – that greater devotion to public service will solve these disparate and varied problems – falls flat. Her analysis of the ‘abuses’ catalogued reads at best naïve and at worst wilfully ignorant of the pervasive and deeply entwined nature of many of the causes of their causes.

May’s non-traditional memoir is an interesting read, giving some insight into cases that continue to puzzle policymakers (Brexit), and memorably controversial cases. However, the underlying message – that greater devotion to public service will solve these disparate and varied problems – falls flat. Her analysis of the “abuses” catalogued reads at best naïve and at worst wilfully ignorant of the pervasive and deeply entwined nature of many of the causes of their causes. This shallow defence of her time in government will do little to help polish May’s image, relying on unsupported claims about the intention of policies, such as those that led to the Windrush scandal, and selective attempts to blame others, as in the case of Brexit.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: pcruciatti on Shutterstock.