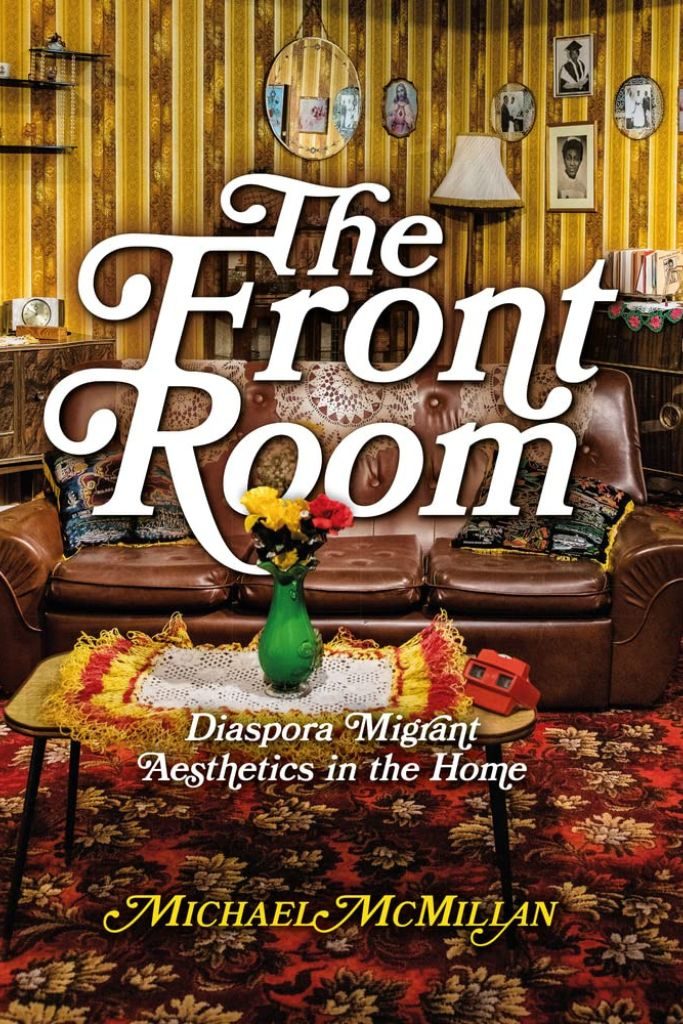

In The Front Room, Michael McMillan examines the significance of domestic spaces in creating a sense of belonging for Caribbean migrants in the UK. Delving into themes of resistance and creolisation, these sensitively curated essays and images reveal how ordinary objects shape diasporic identities, writes Antara Chakrabarty.

Migration, at its most basic level, means a physical relocation. However, this “mobility” entails a complex, polysemous reality whose consequences reverberate for those who leave one place for another. Michael McMillan’s The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home presents a poignant personal tale of materiality, memory and diasporic emotions. It connects with readers by presenting the past without falling prey to anachronism, narrating ordinary aspects of our day-to-day lives through pertinent sociological themes and recurring issues like racism, world politics, aspirations, diasporic memory and more. Michael McMillan, a playwright and artist, offers a text that unfolds as a choreopoem to the domestic spaces inhabited by migrants, infused with theatricality and a curatorial sensibility around the images and references shared. The book, originally published in 2009, has been re-released and is divided across several themes and including additional essays, including by eminent cultural anthropologist Stuart Hall.

Migration, at its most basic level, means a physical relocation. However, this “mobility” entails a complex, polysemous reality whose consequences reverberate for those who leave one place for another. Michael McMillan’s The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home presents a poignant personal tale of materiality, memory and diasporic emotions. It connects with readers by presenting the past without falling prey to anachronism, narrating ordinary aspects of our day-to-day lives through pertinent sociological themes and recurring issues like racism, world politics, aspirations, diasporic memory and more. Michael McMillan, a playwright and artist, offers a text that unfolds as a choreopoem to the domestic spaces inhabited by migrants, infused with theatricality and a curatorial sensibility around the images and references shared. The book, originally published in 2009, has been re-released and is divided across several themes and including additional essays, including by eminent cultural anthropologist Stuart Hall.

Caribbean diaspora re-imagined the Victorian parlour, (the front room) through a sense of decolonial resistance, cultural survival and aspirational attempts to adapt to the new culture in which they found themselves.

The book takes us on a journey of discovery as to what spaces meant, looked, smelled and felt like for Caribbean diaspora settled in the UK from the mid-20th century. It describes how the tactile sensations and emotions held in a room amount to so much more than its aesthetics. The text begins with a section on how Caribbean diaspora re-imagined the Victorian parlour, (the front room) through a sense of decolonial resistance, cultural survival and aspirational attempts to adapt to the new culture in which they found themselves. The images used to showcase the different varieties of such front rooms were mostly taken from the response to the exhibition, A front room in 1976 , curated by McMillan at the Museum of the Home in London in 2005-06.

A primary thematic focus is the emergence of a significant cultural process of change often called as creolisation which gives rise to a third culture which is neither Caribbean, nor British, but a diasporic intermingling of the two. This creolisation also occurs as a result of intergenerational change in the wake of World War Two and apartheid. Moreover, it speaks to the changing imagination around what can be called a “home”, reflecting changes in identity in a foreign land. The lucidity of the essays and the various references to sociological and anthropological works on the perception of “self”, vis-à-vis place making like those by Erving Goffman, Emile Durkheim, Stuart Hall gears the book towards students beyond the disciplinary boundaries of Sociology, Anthropology, Arts and Aesthetics, History, Museology and more. Towards the latter part of the book, McMillan also brings in other diasporic communities beyond the Caribbean, such as Moroccan, Surinamese, Antillean and Indonesian migrant communities in the Netherlands.

Front rooms generally resisted change, carrying forward an aesthetic and sensibility as the badge or identifier of a community.

The book presents an important diasporic narrative underpinned by a critical struggle of the diasporic experience: underneath the subject of the ”front room” lies the process of subverted diasporic emotions and anti-assimilation cultural change. The emotional attachments are prioritised over fitting exactly within the typical British space. McMillan presents his readers with ten commodities that were normally seen in the Caribbean households which were also seen in the diasporic “front room” in the UK. These objects wordlessly communicated the Caribbean way of life without. A homogenisation of the objects found in the across the British Caribbean front room happened gradually as people visited one another, trying to emulate the aesthetics of a diasporic migrant culture. As someone from South Asia, I can vouch fora very similar pattern post-colonisation. Some chose to keep religious symbolic items at the forefront whereas the others chose to fit into the moral definition of aesthetics according to the British. A front room could become a Durkheimian quasi-sacred space which had to be seen beyond its mundane nature. McMillan emphasises the changes across generations and how front rooms generally resisted change, carrying forward an aesthetic and sensibility as the badge or identifier of a community. The book makes its readers aware of the significance contained in the spaces not just through imagery, but also literary compositions like songs, poems, and other varieties of literature.

The gendered division of aesthetics was apparent in the crochets made by the women in contrast to the glass cabinets and drinks trolleys that showcased men’s tastes.

The book describes the affective power of objects through ten examples including the paraffin heater, which gave a sense of reassurance and reminded migrants of their homes through the scent of paraffin oil. The radiogram (a piece of furniture that combined a radio and record player) played the role of “home” in another new land, a sonic gateway into the past. Several other items also acted in service of what Goffman would call ‘impression management’ to a larger audience. The gendered division of aesthetics was apparent in the crochets made by the women in contrast to the glass cabinets and drinks trolleys that showcased men’s tastes. Notably, the carpets and wallpapers, though quintessentially British in theory, could be reclaimed and subverted through the choice of colourful options rather than plain base colours. The book also captures the effects of technological evolution through the inclusion of televisions, telephones and pictures of revered role models such as politicians and singers on display.

McMillan’s work takes account of the constant search for refuge in the perfectly arranged room as a way of way of asserting one’s identity and materialising an authentic diasporic identity in one’s home.

One may make the mistake of perceiving this text as an over-romanticisation of material objects that convey diasporic identity. However, McMillan avoids this, convincing his readers of the deeply felt significance of the ordinary in connecting diaspora to the places they left behind. He bolsters this through setting ordinary items, spaces and lives in the context of unique epistemological nuances such as apartheid, cultural hybridisation, symbolic capital, taste and more. His work takes account of the constant search for refuge in the perfectly arranged room as a way of way of asserting one’s identity and materialising an authentic diasporic identity in one’s home.

The book is successful in its theatrical and thoughtful presentation and the depth it achieves over only a limited number of essays. Its effect is to fill readers’ minds with questions and to pave the way for similar studies in other postcolonial diasporic communities.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: 12matamoros on Pixabay