Alfred Wong

(BSc International Relations)

Image rights: Lay Sheng Yap

(BSc Government and Economics)

Is China losing the New Great Game?

How China’s Central Asian energy strategy is threatened by poor governance in the region.

Today, Central Asia is once again the centre of a contest between the great powers of our time. The United States, Russia, China, and other regional powers are today contesting the ‘New Great Game’ in that same region: for security, for influence, but first and above all for energy — the crude oil and natural gas that power the modern world.

China is the latecomer to the competition for Central Asian energy sources, overshadowed by Russian leverage over its post-Soviet neighbourhood, and by more recent US investments for its war in Afghanistan. However, for over a decade, China has been making up for lost time with an aggressive and expensive campaign to acquire oil and gas supplies and pipelines. While China under Xi Jinping has pursued closer integration and development in other sectors in Central Asia, China’s energy goals in the region remains the centrepiece of its Central Asian strategy.

China’s energy strategy in Central Asia has both an economic and a strategic goal. In the first place, the rapidly expanding Chinese economy generates prodigious demand for hydrocarbon imports. In 2014, China imported 60% of its oil and 30% of its natural gas. China relies on imports for nearly a quarter of its consumed energy. At the same time, Chinese policymakers fear dependency on Middle Eastern energy transported via tankers, which pose a strategic vulnerability due to US naval dominance from the Persian Gulf to the Straits of Malacca.

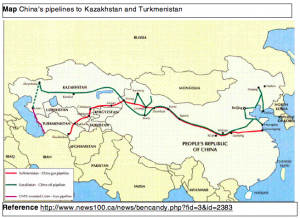

This is why China is playing the ‘New Great Game’ with all the vim and vigour it can summon. In Beijing’s reasoning, if China must be dependent on foreign sources of oil and gas, these sources should be ruled over by friendly, stable (see: authoritarian) governments. In the late 1990s, China began approaching Central Asian states to buy oil and gas supplies, and building pipelines to transport those supplies. Today, China is beginning to reap the fruits of its labours: through the Kazakhstan-China pipeline (KCP), China imports over 86 million barrels of oil annually. The Central Asia-China gas pipeline (CAGP) when completed will run through all five countries in the region to bring up to 85 billion cubic metres of natural gas to China every year.

The plan thus seems simple: China gains a dependable overland energy source from friendly, stable and Sinophile governments in Central Asia. The problem with this reasoning arises in the assumptions made about the dependability of Central Asian governments. The five post-Soviet republics of Central Asia do appear stable; indeed, two of those republics have not had a different President since their founding. However, a closer look at the region reveals that this stability is largely superficial, masking governance failures that threaten China’s energy strategy. According to the International Crisis Group (http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/files/asia/north-east-asia/244-chinas-central-asia-problem.pdf), “many Chinese scholars argue that its (China’s) biggest long-term security concern there (in Central Asia) is internal turmoil within the regimes and its effects.”

Regime type. Von Hauff, 2013 (https://dgap.org/en/article/getFullPDF/23597) defines Central Asian regimes as ‘patrimonial-authoritarian’, meaning that Central Asian governments generally rule through a combination of authoritarian presidential institutions and informal networks of vested interests. The regime type prevalent in Central Asian states is arguably the root cause of poor governance in Central Asia, which then create or exacerbate the various second-order governance failures listed below.

Succession risk. The succession issue is both more important and more difficult to resolve in Central Asia due to regime type. Political stability is often dependent on what little legitimacy is conferred by national leaders, based on Kazakhstan’s relative prosperity and Uzbekistan’s relative stability. However, neither Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev, who is 75, nor Uzbekistan’s Karimov, 77, have clear plans for their succession, as such plans would weaken them politically. The succession question is an uncertainty inherent in Central Asian governance structures which reduces the strategic value of China’s commitment to Central Asian oil and gas.

Corruption. Rent-seeking is an integral component of patrimonial-authoritarian regimes, and inevitably reaches the highest levels of government. All five of the Central Asian states rank below the 70th percentile of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index in 2014 (https://www.transparency.org/cpi2014/results). Corruption destabilises the business environment, even for the Chinese government, because corruption weakens the state structures meant to guarantee China’s energy investments.

Labour unrest and industrial action. Central Asian governments’ inherent aversion to institutionalised political opposition (possibly excepting post-2005 Kyrgyzstan) means that there are no effective, independent unions. Industrial action is thus the only outlet for workers’ complaints. This can seriously endanger both oil and gas production, and the subsequent transportation of these oil and gas supplies to China. One stark example is the seven-month 2011 strike in Zhanaozen, Kazakhstan by oil workers, which cost $365 million in lost revenues and ended in 17 strikers killed.

Intraregional resource conflicts. Domestic governance problems are exacerbated by the interdependence in energy and water between the Central Asian states. One of the legacies of the region’s Soviet past is Kyrgyzstan’s and Tajikistan’s reliance on Uzbekistan for natural gas, and Uzbekistan’s converse dependence on Kyrgyz and Tajik water supplies. The three parties

In an attempt to rectify these governance failures, Beijing is making moves on other fronts in the ‘New Great Game’. Xi Jinping’s administration is seeking to bring peace and prosperity (although not necessarily in that order) through the $40 billion ‘New Silk Road’ initiative and the $50 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. China’s leadership of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation also aims to stabilise the Central Asian states. Finally, the legal ownership structures of the two major Chinese pipelines are also designed to ensure China’s control over them.

So is China losing the ‘New Great Game’? It is too early to tell: both China’s energy strategy and the governance failures that threaten it are long-term issues which could unfold in any one of a thousand ways. China is also deploying unprecedented sums of money to Central Asia in support of its goals. However, what is blatantly clear from observing the situation today is that China’s disregard for the systemic governance failures in Central Asia — failures which threaten its pursuit of energy security there — appears short-sighted and ill-considered.

The information and views set out in this blog article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the LSE Undergraduate Political Review, nor the London School of Economics.

Yes, there is risk of regime instability in central Asia but please don’t go so far as to claim that Chinese policy makers are all “short-sighted and ill-considered”. What is a better strategy? As you have noted, US naval dominance poses an existential threat to China’s energy supply and industrial production in general. Despite all its talks about “free navigation of the sea”, US is probably the most frequent imposer of naval blockades.While no one is hoping for a confrontation between the two countries, strategically Chinese policy makers need to be prepared for the worst — finding new routes of energy imports is a must. Given that building pipes from Central Asia is necessary, the best thing China can do then is to increase regional stability there. How do we do that? Well, as history has proven, a robust economy and greater access to economic opportunities for all sections of the society is the best guarantee against instability. Investing heavily in infrastructure in Central Asia does exactly that and thus proves a realistic and wise policy for China.

Respectfully,

Yucheng

To clarify, I certainly do not think that Chinese policymakers are all “short-sighted and ill-considered”. I know for a fact that the vast majority of Chinese policymakers are experienced, skilled, and patriotic people who want to serve their country as best they can. My point is not about policymakers but about policy.

Neither do I dispute that China is justified in seeking alternative, overland energy supplies from Central Asia as well as from Russia, which is a separate and fascinating topic. But my point is that China’s energy policy in Central Asia either ignores or does not sufficiently account for the governance deficit in the region. China is indeed pursuing regional stability through economic investment and other methods, but this approach doesn’t deal with the fundamental problems of corruption, regime fragility, etc. in the region. In fact, China’s preferred diplomatic approach of heavy investment and aid is likely to worsen the governance situation in Central Asia by fuelling the corruption of regime elites and increasing popular dissatisfaction against those regimes, not to mention against China. As I strongly doubt that Zhongnanhai is unaware of the governance situation in Central Asia, my conclusion is that their overwhelming focus on the energy security available from friendly, neighbouring Central Asian regimes has blinded them to the risks from the governance deficit in the region.

Thank you for your thoughtful reply,

The author

I find this article difficult to follow in two ways: firstly, from the last three paragraphs I can see both the risks facing China’s Central Asia policy and China’s recent attempts to resolve them, but I can hardly find any evidence in this article to support the conclusion that China IS disregarding the problem of governance in this region. Secondly, I think given the capital-intensity (and in many cases, also the geographical remoteness) of most investment projects in the energy sector (either for resource extraction or for resource transportation), the establishment of a causal link between poor governance (as described in this article) and poor investment return (or security) in this sector requires more evidence, or perhaps even a more systematic analytical framework than this article has offered.

Thank you for your comment. I’ll first respond to your second comment, about my definition of the ‘New Great Game’. The core of my understanding of this concept is in the first paragraph, but to expand on what I mean, the New Great Game today consists of the competition between Russia, China, the US and other countries (including India, Pakistan, Iran, and others), for influence and energy resources in Central Asia. Russia’s motivation is complex, encompassing military (Russian military bases in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan), economics (millions of Central Asian migrants work in Russia, and Gazprom historically has had a high stake in Turkmen gas), and nationalism (ethnic Russians in CA), reflecting the Soviet legacy in both Russia and the Central Asian states. China’s motivations I believe are primarily economic- as well as security-oriented (the East Turkestan Islamic Movement is partly based in Central Asia http://www.cfr.org/china/east-turkestan-islamic-movement-etim/p9179). The US interest is a legacy of the Afghanistan war where the American military depended on the Northern Distribution Network spanning Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan for an alternative supply route from Pakistan.

The link to the historical ‘Great Game’ is that these three countries see their own interests as at least partially mutually exclusive with those of the others: Russian interests in maintaining a monopoly over Central Asian energy to export to the European market is threatened by China’s moves to connect CA energy to China; the massive psot-9/11 US military and financial presence in CA was seen as a threat by Putin after 2003. The concept of the ‘New Great Game’ is disputed by some analysts, but I believe it adequately captures the current situation of extraregional international relations in CA while linking it to the historical version of that situation.

Re whether China is disregarding CA governance problems: I do not believe that China is unaware of these problems, but rather that China is ignoring them in its energy strategy in order to pursue its own goals, which in the medium- to long-term will backfire. My conclusion that China is disregarding these problems stems from my observation of China’s attempted solutions to them, specifically the economic/financial, multilateral, security-related, and legal measures. My view is that while China is making an honest and serious attempt to engage with the regimes, its approach does not tackle the core problems of regime type, corruption and the others I’ve outlined.

Re the link between governance and investment return/security: forgive me if I’m unclear on your argument, but in my view, neither geography nor capital intensity reduces the link between poor governance and reduced strategic value of energy assets. My view, which is significantly expanded in the full article of which this blog post is only a summary, is that poor governance in Central Asia is the cause of the various problems I’ve outlined in this post, each of which negatively impacts the strategic value of CA oil and gas to China by heightening the medium- to long-term risks that China will be unable to access these resources. The scope of my article does not include the investment returns to China’s CA energy investments, however, and instead my focus is on Beijing’s belief in the supposedly safer and more secure energy supply that CA provides.

Thank you for your insightful comments, I hope that either my response or my full article (to be published by LSEUPR soon) will answer your questions.

The author

Also, I wonder if the author of this article can provide a more concrete explanation of the term ‘the new great game’, as the contemporary scenario seems to deviate largely from the one in the 19th Century.