“The people must get their nation back.”

In November 2023, the Netherlands saw what is being dubbed one of the biggest political upsets since the Second World War. After 25 years as a minority voice in the Dutch parliament, Geert Wilders is set to become the leader of yet another far-right government in Europe. Some of Wilder’s main stances include fervent anti-Islamism, strong opposition to immigration, and general economic concerns over the housing and the cost-of-living crisis.

While the possibility of a far-right government was a shock for the Netherlands, it is only the latest of similar worrying developments in Europe. Wilder’s Party for Freedom (PVV) is the fourth far-right party to gain power in an EU state in recent years, following Hungary and Italy. Austria, France and Germany are expected to follow, with the far-right Freedom Party, the National Rally, and the Alternative for Germany, polling higher than the current governments. Europe is undeniably being hit by a wave of “new populism” – a phenomenon where anti-establishment, nationalist, and populist values combine in a reaction against economic recession, the migration crisis, and the cultural shifts brought by globalism.

“I am very concerned with what is happening in Europe concerning extreme political parties in general. This poses some problems concerning the unity of the EU […] We have spent much work on the EU Migration Pact and we will sustain this pact whatever it takes.”

Those were the remarks of Professor Georgios Gerapetritis, foreign minister of Greece, when he was asked to comment on this trend during his visit to LSE in November. With regard to the Euroscepticism of far-right leaders, he highlighted that ‘we are very hopeful that this [agenda] will change’.

A Historical Outline

Certain empirical claims could be made about this worrying development, which may give us insight into its causes and possible solutions.

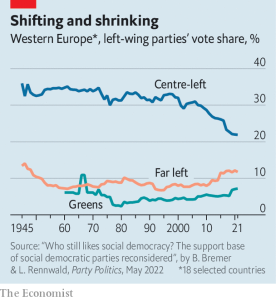

Firstly, it seems the current political ‘battle’ in Europe has shifted from a Left/Right division to a debate between global liberalism and anti-liberal, traditionalist ideas. This signifies a general shift to the right, where the traditional left has lost its appeal and subsequently its force as a power in opposition. Instead, opposition to the establishment (which vaguely includes all centrist and centre-right liberal governments) comes from the new hard-right, which combines populism with conservatism to counteract the forces of globalism and the ‘cultural left’.

Secondly, in countries with a de facto two-party system, such as the United Kingdom, an internal shift to the right has been taking place within the current government and opposition parties, with Tory frontrunners embracing right-wing rhetoric, while a significant portion of Labour have abandoned the party’s socialist heritage.

Thirdly, it seems voters themselves are abandoning the traditional Left/Right division as the reactionary, anti-establishment elements in far-right parties have gained the support of both the working class and the anti-authoritarian left. Parties no longer run on socialist or capitalist platforms but shape their identity around the growing disapproval of the government’s handling of social issues, such as migration, the housing crisis, and the economic mismanagement of Europe.

What caused this?

The rise of the new far-right is not an unexpected phenomenon. Economic, social, and political affairs culminate to act as different factors, beginning in 2007 with the Great Recession. These factors can be grouped and analysed as the ‘triggers’ of one of the greatest insurgencies of far-right politics since the end of the Cold War.

Source: The Guardian

Vital to enabling support for their social policies, economic factors form the backbone of support for the far-right. In their analysis of the far-right rise in the 21st century, Georgiadou, Rori and Roumanias find a significant correlation between economic insecurity – including high unemployment and negative GDP growth – and support for what they call the ‘extreme right’.

Worsening economic conditions, particularly high unemployment, primarily fuel the social outrage that manifests as support for anti-immigration policies. The researchers found that extremist right parties amplify their opposition to immigration ‘through … feelings of economic insecurity’ driven by high unemployment. I believe economic factors are necessary for the recruitment of previously apolitical working-class individuals who attribute blame for worsening conditions, high crime rates, and unemployment to immigrants. Blame is also placed on perceived ‘globalism’, which carries economic consequences such as the globalised import economy and social factors like increased migratory flows and multiculturalism. This allows for far-right social ideology, typically characterised by hard protectionism and nationalism, to arise.

Supporters of the Italian Social Movement (MSI) give fascist salutes in January 2024 to commemorate the anniversary of the death of two neo-fascists in 1978. (Credit: Francesco Benvenuti / AP)

The social changes that led to the rise of the reactionary ‘alt-right’ in the US during the 2016 Elections have recently started affecting Europe. These changes primarily involve what far-right politicians see as attacks on tradition and the ‘national spirit’, ranging from support for LGBTQ+ rights, environmental concerns, Islam, atheism, and family forms incompatible with the traditional European nuclear model. Most far-right party political platforms identify migration as the greatest social ‘threat’ to the Western national spirit, particularly the rise of Islam in historically homogeneous Christian Catholic and Orthodox societies. In Western Europe, migration has had the greatest cumulative impact on France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Austria and Sweden, where Muslim populations have grown significantly since the start of the century. The far-right denounces immigration as an ideological challenge, accusing immigrants of resisting cultural integration, thereby diluting the West’s national spirit, and as a pragmatic attack on Europe, based on sweeping generalisations linking immigrants to increased crime rates.

Political Factors

Two main political factors have predominantly facilitated the mainstreaming of the far-right in European politics. The first is the prevalent disunity of left-wing opposition parties in Europe. The second is the mismanagement of the economy by neoliberal centre-right parties and the perceived lack of a possible alternative, or what Peter Mair called “The Hollowing of Western Democracy”.

While the far-right’s social platform is centred around opposition to the ‘cultural left’ (LGBTQ+, immigration, climate crisis, etc.), their political and economic targets primarily align with the right. Their most consistent political activism revolves around the state of the working class, which they perceive as neglected by traditional politicians. This is not an attack on left-wing politics; rather, it critiques the neoliberal economic order, which they believe has failed regular citizens amidst the economic and political crises that hit Europe since 2008. Except for brief periods in Germany and Greece, left-wing parties have not formed stable governments after 2010, and thus the blame for the current economy falls on the traditional centre-right and right-wing neoliberal governments in power during the 2009 crisis, which largely continue to govern Europe today.

The rise of the far right can be attributed to two main political factors. Firstly, the lack of strong opposition from the left, evident in countries with multi-party systems where the opposition vote is distributed amongst several anti-capitalist, socialist and communist parties. This fragmentation has allowed far-right parties, who can amass more concentrated support due to their smaller number, to rise as the ‘defenders of the nation’, and those that most staunchly oppose the status quo. Secondly, the adoption of neoliberal economics as the status quo for the modern European Union, and its continuous failure to prevent the economic crises of 2008 and 2020, combined with dying support for left-wing socialism, allowed for the far-right to gain traction as the ‘alternative’ route for citizens who are tired of the precarious economic conditions. This dissent manifests itself in Euroscepticism, the rise of which threatens the stability of the European Union as an economic and political project.

Source: The Economist

Finally, fascism doesn’t always replace the neoliberal status quo from the outside – it can also arise through internal party transformation. The recent reshuffles of the British Conservative cabinet have led to a much more right-wing and conservative cabinet consisting of non-elected officials, all through a process mainly devoid of public input. The political blunders and extremist rhetoric of Suella Braverman as a short-lived Home Secretary are a testament to how mainstream politics can be infested with right-wing elements in plain sight.

How Can We Stop It?

The rise of the far right and modern fascism poses a significant threat to Europe’s democratic order, but it is not inevitable nor all-powerful.

Firstly, reuniting the progressive left is vital in creating a unified opposition against the far-right surge. The electoral advantage that populist parties hold is their undefined, reactionary programs, which resonate with a large portion of the right wing population. Antithetically, leftist and progressive political movements often struggle with fragmentation, political polarisation, and a lack of unified leadership. This parliamentary image is a breeding ground for the rise of the far right. Take France, for example, where the absence of a robust leftist opposition has allowed Marine Le Pen’s populist forces to emerge as the main challenger to Macron’s neoliberal policies. Progressive movements must regain public support by embracing unity, avoiding their tendency for exclusion, and possibly adopting a softer stance at the expense of greater impact for the benefit of mass support.

Secondly, improving social and economic conditions will undoubtedly curb the appeal of populism, but that must be paired with a departure from the entrenched neoliberal economic paradigm. With the death of the new left, the ‘old right’ has taken over European economics and has provided no true political solutions. In his book on democracy in Europe highlights, Peter Mair suggests that both the mainstream centre-right and centre-left parties in Europe operate on a default platform of neoliberalism, perpetuating the status quo rather then challenging it. This fear of risky economic steering makes it easier for parties to attack each other over comparable policies, but also removes the opportunity for the people to express their dissent through elections. Thousands march in front of the German Reichstag on the 21st of January 2024 during large-scale protests against the AfD and right-wing extremism. (Credit: Ebrahim Noroozi / AP)

Thousands march in front of the German Reichstag on the 21st of January 2024 during large-scale protests against the AfD and right-wing extremism. (Credit: Ebrahim Noroozi / AP)

Finally, liberalism’s tolerance in the name of democracy and anti-censorship has inadvertently fuelled the growth of hateful and reactionary ideologies. European fundamental rights should be limited to protect the integrity of the state, and parties promoting discriminatory, harmful, and anti-democratic rhetoric should be barred from mainstream platforms. In Greece, the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party’s criminal convictions did not stop ex-party representative Ilias Kassidiaris from indirectly supporting and running a new ultra-right-wing “Spartans” party. With constitutional law and authorities in deadlock, the liberal system must find a way to uphold the rule of law while protecting democracy. Constitutional courts across Europe should strike a balance between fundamental rights and enabling the spread of ideas dangerous to democracy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the rise of the far-right in Europe is the natural consequence of political decline combined with the social and economic struggles that most of the world faced after the economic crisis. It is a worldwide phenomenon, which is amplified as calls for progressive change intensify. As with every turbulent moment in history, it is a growing threat, but it cannot affect the future unless we allow it to. It is within our power to put an end to the hateful and undemocratic politics of populism and defend liberal values, human rights, and the rule of law.

By Iason Kazazis

Cover Image: Demonstration gegen rechts in Frankfurt by Ostendfaxpost via Wikimedia Commons

amazingly written and very insightful article!