Author and Image rights: Lay Sheng Yap (BSc Government and Economics)

The Politics of Ai Weiwei

Activism and art are one, claims Ai Weiwei. His recent exhibition at the Royal Academy has garnered favourable reviews commending him for his political activism against the Chinese state. The media has variously portrayed his art as “political”, “bold” and as a figure defiant “in the face of authority on behalf of freedom of expression”. However, this simplistic representation of Ai Weiwei as the dissident artist conceals the complex relationship Ai shares with the subject of his art work. I propose that we re-examine Ai Weiwei’s relationship with the Chinese state and its oppressed, and in doing so, refute the media’s reductionist account of Ai and the Chinese state as a simplistic model of the dissident against the hegemon.

Ai Weiwei’s art is conflicted: it simultaneously expresses solidarity for those suffering from oppression, and silences them in the course of his artistic production. In a piece titled Straight (2008–12) — where he straightens rods salvaged from the rubble of the Sichuan earthquake — he gives form to the suffering experienced by the family members of the deceased victims as a result of negligence of the Chinese state. In another work Bones (Remains) (2015) – porcelain replicas of an actual set of bones, supposedly modelled after the bones of activists exiled during the Anti-Right campaign — he once again demonstrates comradeship with the oppressed. The theme of solidarity constantly resurfaces as Ai seeks representation for those unfairly implicated in the cruelty of the state.

It is no wonder then that Ai is the darling of Western liberal media. This is the simplistic narrative that the media tends to portray: Ai is a martyr against the relentless onslaught of Chinese authoritarianism, one which has made him suffer imprisonment, censorship and great restrictions on his movement. However, to make a claim like that lands us in deep intellectual conundrum. Ai Wei Wei’s source of inspiration is the muted anguish of the oppressed: metal rods from collapsed schools after the Sichuan earthquake and ashes of the exiled; these artistic materials are residual debris from the aftermath of the event. How are the subjects (of his art) to be comprehended through inanimate objects he painstakingly salvages? How are they expected to reclaim their subjecthood when they are dead? In Ai’s “5.12 Citizens’ Investigation” project, he aestheticizes the death of schoolchildren in large spreadsheets through a process of abstraction away from the individual. The identity of these children and their individual subjecthood are completely effaced to fit a coherent narrative of the simplistic binary between oppressed (the dead) versus the oppressor (the state).

The expression of solidarity requires a reciprocity of power, a mutuality of communication between the artist and his comrades/subjects. Ai’s statements, however, reveal otherwise:

“Honestly speaking, those children who drank the poisoned melamine and died before they could understand this world, they had no chance to say what needed to be said. Analogous things happen all the time. It is necessary for someone to speak out, is it not? Compared to ordinary people, I have an advantage, capability, and aesthetic ability to make my voice heard. Why shouldn’t I speak? If I did not do this, I would insult myself (Ming, 2010).”

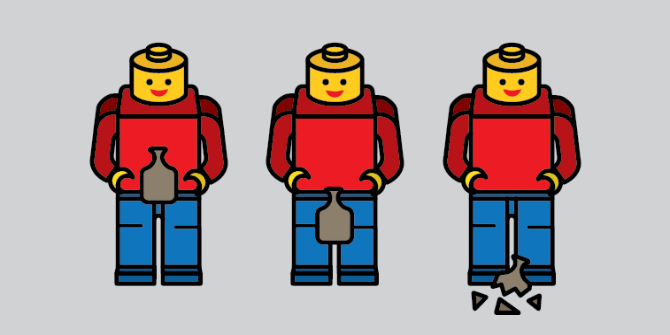

In Ai’s situation, there is vast dissymmetry of power and media attention. The subject is excommunicated from his artistic process. He himself acknowledges that “they had no chance to say what needed to be said”, and in their place, he had to “make [his] voice heard”. Viewed in this manner, Ai’s expression of solidarity is really a ‘spokespersonship’. A spokesperson, according to Pierre Bourdieu, is someone who speaks on behalf of another, rendering the represented party invisible and silenced. Ai enjoys this duality of role: as a dissident against the hegemon in one narrative constructed by Western media and, in the other, assumes the role of the hegemon who authoritatively reconstructs the narratives of his represented subjects. In this dynamic of spokesperson and those who are spoken-for, the latter (such as the victims of the Sichuan earthquake or the exiled activists whose bone-casts Ai displays) renounces any independent control over their subjecthood when this authority is delegated to the more powerful actor: Ai the artist. In the process, these represented subjects are further alienated in the political process. They suffer, in the first instance, from oppression through the violence of the state, and in the second, from oppression through a dynamic of ‘spokespersonship’ that they enter involuntarily.

How should we confront this predicament of the oppressed? How do we represent them without doing violence to their subjecthood? To contextualize Gayatri Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in this scenario, the answer is ‘no’. The ‘subaltern’, as a concept borrowed from Antonio Gramsci‘s “The Prison Notebooks”, refers to any class or sub-class of individuals of “lower rank” whose ability to define themselves is limited by the hegemon’s narrative power and domination. For Gramsci, the “subaltern classes by definition, are not unified and cannot unite until they are able to become a ‘State’” (Gramsci, 1971). What Gramsci denotes as the subaltern is not merely a position of inferiority. By the very relegation of their status as the subaltern, they are undefinable, “are not united” and “cannot unite”. They (even ‘they’ as a pronoun flattens the heterogeneity of this class) are defined negatively through the State or the hegemon. According to Gramsci, the history of the subaltern is “intertwined” with the “history of States”, and it is this mutual dependency that defines the meaning of the ‘subaltern’ and the ‘state’. To lend the ‘subaltern’ direct representation is to immediately destroy its situational context. To bridge the gap between the hegemon and the ‘subaltern’ is to immediately displace the identity of the ‘subaltern’ onto another group, class, or individual.

This leaves us in a dilemma: Ai’s attempt at defining the subaltern renders incognito their identity, but without consolidation of oppositional movement in China, the state will remain dominant. Ai’s politics is to present a cohesive voice against the state, but in doing so, he sacrifices the subjecthood of those he claim to represent. As Ai remarked recently, “[My supporters] use me as a mark for themselves to recognise their own form of life: I become their medium. I am always very clear about that.” (Guardian, 2011) This is the politics of Ai Weiwei—the problematic of assembling a coalition against the state degenerates into a relationship that serves the interest of the “medium” more than it does the marginalized.

Bibliography

Gramsci, A., 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. 2sd ed. New York: International Publishers.

Guardian, T., 2011. Ai Weiwei: ‘Every day I think, this will be the day I get taken in again…’, London: The Guardian .

Ming, Y., 2010. A Classical Schizophrenic: Ai Weiwei’s Life of Art [Interview] (11 August 2010).

The information and views set out in this blog article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the LSE Undergraduate Political Review, nor the London School of Economics.