by Tobias Thiel

After ten months of deliberations, Yemen’s 565-member National Dialogue Conference (NDC) closed its doors on January 25, 2014. The NDC was the flagship of Yemen’s negotiated transition process. Jamal Benomar, the UN Special Adviser for Yemen, widely advertised the transition as a model for averting a Syria-style civil war in the violence-riddled Arabian republic. He pronounced the NDC an ‘unprecedented achievement in the history of Yemen’—nothing short of a ‘miracle’—and described it as ‘the most genuine, transparent and inclusive national dialogue the region has ever seen.’

The trajectory of Yemen’s transition, however, is far less hopeful than the language of diplomacy suggests. Whether or not the negotiated transition has averted a civil war in Yemen remains purely speculative, and—even if it has done so indeed—is no guarantee for a peaceful future. Also, the NDC is not historically unprecedented in a country with a strong tradition of conciliatory conferences—some of which have culminated in bloodshed. Looking forward, the litmus test is thus not the consensus reached in the NDC, but whether the US$40,000,000 conference can engender tangible political, economic, legal and social reforms.

A History of Dialogues

National dialogues, in one form or another, have a long history in Yemen. Besides numerous tribal-political congregations during the millennial rule by Zaydi Imams (897-1962), Yemen’s modern history is replete with conciliatory conferences. Yemenis convened a national conference in Haradh as early as November 23, 1965. Three years into the royalist-republican civil war, the 55 delegates were entrusted with determining the preliminary shape of North Yemen’s political system, appointing an interim government and deciding on the modalities of a plebiscite to settle the monarchy-republic dispute by ballots rather than bullets. The consultation started out amicably, but as a contemporary pressman observed, ‘it [was] the dialogue of the deaf. Both sides talk, but neither side listens.’ Overshadowed by violence, the conference broke down.

Between 1980 and 1982, former President Ali Abdullah Salih organised hundreds, perhaps thousands, of discussions on a nationwide scale under the umbrella of the National Dialogue Committee to bolster regime legitimacy. It was—as the current NDC—architected by then Prime Minister Abdulkarim al-Eryani. The National Pact that emerged from these meetings constituted the basis for the General People’s Congress (GPC), the dominant political organisation of the Yemen Arab Republic until it transformed into a political party after unification in 1990. This series of conferences was successful in building a mechanism for state-society relations.

Another dialogue convened from November 1993 to February 1994: the National Dialogue Committee of Political Forces. An extraconstitutional 30-member body with a fair representation from all significant national factions and regions, the committee prepared the Document of Pledge and Accord. This popular conciliation agreement equitably reflected the reform agendas of the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) and the GPC to resolve the political impasse between the newlywed North and South. Although Salih and his southern rival, Vice-President Ali Salim al-Beidh, signed the agreement in February 1994, Yemen plunged into a full-fledged civil war less than two months later.

In February 2009, the GPC and the opposition coalition Joint Meeting Parties (JMP) agreed to postpone parliamentary elections by two years and hold a National Dialogue on electoral and constitutional reforms. The National Dialogue, which only materialised in August 2010, became a public performance to garner legitimacy for the GPC, while opposition elites appeared more interested in political concessions than genuine reforms. The dialogue remained stillborn.

The Architecture of the Transition: A Just Solution?

Yemen’s 2011 uprising prompted the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) to broker a power transfer agreement, which—after months of foot-dragging, tit-for-tat and violence—was signed in November 2011. The deal granted former President Salih immunity in exchange for his resignation and set down an ambitious 2-phase roadmap. In the first 90-day phase, Salih transferred presidential authority to Vice-President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who appointed a national unity cabinet and established a military committee to restore public security. In February 2012, a popular referendum confirmed Hadi as president for a two-year term.

In the second phase of the roadmap, Hadi oversaw the restructuring of the armed forces and the NDC. Eight months behind schedule, the envisaged constitutional and electoral reforms, as well as the parliamentary and presidential elections originally scheduled for February 2014, are yet to materialise. The GCC initiative left Yemenis with a feeling of injustice. Conceived by a club of monarchies with stability rather than change in mind, it aborted Yemen’s revolution and granted impunity to Salih. To make matters worse, the JMP—who was seen to have hijacked the revolutionary movement—signed the initiative into force.

Besides the dubious legality of the immunity deal, the agreement contained a fatal flaw: it retired Salih from the presidency, but not politics. He remained the chairperson of the GPC and plays a poisonous role in sabotaging the transition. Sanctions under a recently passed UN Security Council resolution may provide some alleviation. The architecture of the NDC, on the other hand, did provide a constructive forum for political dialogue, which—arguably correctly—prioritised inclusiveness over effectiveness. This priority inevitably staked the success of the conference on back-channel agreements among elite powerbrokers, which would be legitimised in official NDC deliberations.

In practice, however, the NDC scored poorly in terms of transparency, inclusiveness, outreach and effectiveness. Apparently undisturbed by procedural details, the deferral of decisions on the most crucial issues to exclusionary committees lacked transparency. As the conference approached its official September 18 closing date without agreement, a subcommittee with eight representatives from each north and south, known as the 8+8 Committee, was charged with finding a solution to the southern issue. Important parties were excluded in this parallel track of negotiations, but its recommendations were simply accepted as part of the final NDC agreement.

Likewise, the decision about the number of federal regions (2, 5 or 6) was deferred to a separate 22-member GPC-dominated committee. Under protest from the YSP, Hirak and the Huthis-affiliated Ansar Allah, President Hadi announced in February that agreement had been reached on a six-region setup. Ali al-Bukhaiti, a charismatic spokesperson of Ansar Allah, who sleeps in his office with only a teakettle and a Kalashnikov, pointed out that the deferral violated NDC procedures. Lastly, the consensus committee, a group handpicked by the president, finalised much of the pending resolutions.

Insufficient attention to the buy-in of Ḥirāk, the southern movement, jeopardised the inclusiveness of the NDC. Most of its leadership abstained or resigned; Mohammad Ali Ahmed, a former southern interior minister, pulled out of the dialogue. The participating Hirak delegates had no mandate to negotiate on behalf of southerners and, as one delegate dramatically remarked in a personal interview, ‘we will be killed if we bring anything less than independence back home.’ Despite the inclusion of marginalised groups, powerful legacy families dominated the dialogue and Yemenis resented the heavy footprint of the Benomar office.

Most crucially, the NDC became a complete public relations failure. The conference remained as remote to the Yemeni people as is its venue, the Mövenpick Hotel, a 5 star bastion on a hill overlooking Sana’a with daily room rates exceeding the monthly salary of a mid-level ministerial employee. The stipends of delegates of US$100 to $180 per day also stirred resentment. The NDC’s meagre media budget and lack of strategy turned public outreach into little more than window dressing, particularly given that 7 in 10 live in rural areas and are dispersed over more than 110,000 settlements.

Though premature to judge the NDC’s effectiveness, the densely written 352-page final communiqué is a confused repository of around 1,500 recommendations. As one NDC delegate put it, ‘having 1000 recommendations is the same as having none.’ For implementation, the Guarantees Document fails to provide a concrete plan and relies too heavily on newly founded committees rather than bringing existing governmental agencies on board. While the NDC monopolised politics in Sana‘a for almost a year, it did nothing to alleviate the deteriorating humanitarian and security situation in the country’s periphery. Despite the absence of major security incidents, the NDC was unable to guarantee the security of all its delegates. Two Huthi members, Abdulkarim Jadban and Ahmed Sharaf ad-Din were assassinated, ad-Din during the drafting of the final communiqué.

Realities on the Ground

The National Dialogue was cursed by a thoroughly unfavourable political environment. Yemen’s economy contracted in 2011 by 10.5 percent and has not yet regained pre-Arab Spring levels. The poverty rate increased from 42 to 55 percent between 2009 and 2013. Corruption is endemic in the public sector, with hundreds of thousands of ghost workers existent only on payrolls. The Supreme National Authority for Combating Corruption (SNACC) lacks the teeth to implement much needed anti-corruption measures. Unemployment and poor basic service delivery, two key grievances driving the revolutionary uprising, continue unabated.

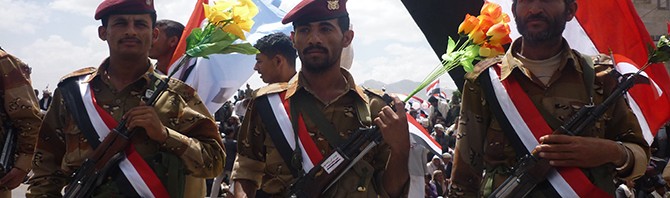

Politically motivated violence has proliferated in Yemen’s power vacuum since 2011. To mention only a few incidents, three months after Hadi was sworn in, a suicide bomber killed about 100 Yemeni soldiers during a rehearsal for the Unity Day parade. In December 2013, Al-Qaida launched a barbaric attack on the Ministry of Defence hospital, killing more than 50 unarmed civilians. Close to a hundred military and intelligence officers became the victims of assassinations in 2013. US drone strikes with high civilian casualties further aggravate the situation. While kidnappings have proliferated in the capital, tribal attacks on energy infrastructure have scourged Yemen’s economy.

However, terrorism and sabotage are not even the gravest problem when compared to the sustained challenges to state authority in much of Yemen’s territory. Tribal resistance continues unabated in Hadhramaut, Marib and elsewhere. In the south, few people view unity as a viable long-term option and its divided leadership try to outbid each other politically in their calls for southern independence. Hadi’s transitional government failed to restore ties with Saudi Arabia, who—worried about a united, democratic Yemen—tacitly supports southern independence.

The war in Yemen’s North along Huthi-Salafi and Huthi-Hashid lines has overshadowed the transition process. On October 30 last year, major fighting erupted as Huthis accused Salafis of recruiting foreign fighters under the cover of a religious seminary in Dammaj. Fighting spread to Arhab as tribes from the Hashid tribal confederation joined in against the Huthis. Though often framed as a Sunnis-Shi‘a struggle, the conflict results from material interests. After a series of failed ceasefires, the Yemeni army was deployed in the province of Amran in January to monitor a fragile truce. Major general Ali Muhsin—a veteran of six wars against the Huthis between 2004 and 2010 and close ally of the president—advocated a stronger army involvement, but Hadi has so far refused to let the government be dragged into the conflict. The war has a catastrophic effect on national politics: it raises doubts about the government’s ability to rule over Yemen’s periphery and exposes Hadi as a weak and irresolute leader.

However, Yemen’s chaotic elite politics is part of a ‘normal’ process of extra-institutional bargaining as powerbrokers seek to expand their political influence, maintain material interests and renegotiate their place in a post-transition social contract. The upcoming constitutional drafting is bound to run into difficulties, most of which will prove politically manageable. The bottom-up state-building project in six autonomous areas, many of which have never been under central governance, is infinitely more difficult. Federalism is perhaps the only viable system to govern Yemen’s pluralistic power centres, but its pitfalls are considerable: low local capacities, contentious resource allocation, the risk of decentralising corruption and the potential domination of regions by powerful elites. Labour-intensive projects are essential for overcoming the insecurity and economic volatility that often accompanies sweeping change processes. However, these short-term measures must not come at the expense of long-term reforms. Renewed demonstrations on Friday show that Yemenis are not ready to accept anything less than a fundamental overhaul of Yemen’s social and political fabric.

Tobias Thiel is a PhD Candidate at the LSE’s Department of International History. His dissertation is about contentious politics, collective memory and violence in post-unification Yemen. He has spent the past three years in Yemen conducting field research.

Tobias Thiel is a PhD Candidate at the LSE’s Department of International History. His dissertation is about contentious politics, collective memory and violence in post-unification Yemen. He has spent the past three years in Yemen conducting field research.

3 Comments