by Karen E. Young

This memo was presented at a workshop in Rabat on ‘The Ethics of Political Science Research and Teaching in MENA’, organised by the LSE Middle East Centre and King Mohammed V University in Rabat on 9-11 June 2015.

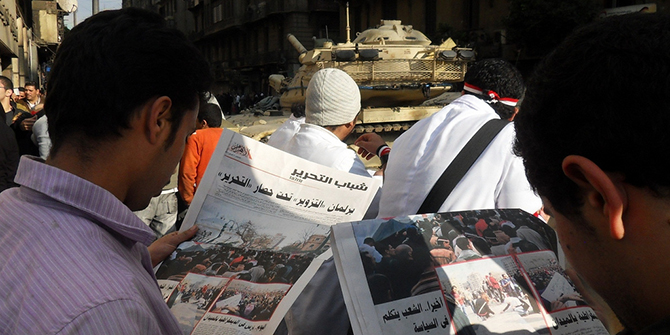

Parts of the MENA region are experiencing what many countries in Eastern Europe faced after 1990—a surge in research interest, some academic ‘tourism’, and a policy and academic fascination with regional upheaval. On the ground, political changes, violence and accompanying securitisation have created some predictable difficulties but also some unexpected challenges for researchers. With increased attention, has come opportunity; yet, most of the research opportunity has been granted to those visiting from afar. Unlike the post-socialist transitions in Eastern Europe in the early 1990s, in which many Western philanthropic and civil society organisations made footholds locally, the MENA region has had a more guarded approach to foreign-funded organisations. The result is an environment in which locally based researchers are facing increasing scrutiny of their work, while many researchers from outside the region have better access and funding opportunities. With few local organisations to support social science research, survey work, and media outreach, researchers based in the MENA region often must settle for support roles in research projects that ‘parachute’ in from abroad. Local researchers are then less a part of the research agenda, the formulation of human subject protocols, and take less credit for the research results and publications. Furthermore, local researchers may be at risk when sharing contacts and networks in ways that visiting researchers do not always appreciate.

The perils are clear. Universities can be on the front-line of changed security policies and of attempts to curtail discourse and engagement with vulnerable and/or opposition political communities. What this means for early-career researchers based in states in political transition (or rejecting political opening) is a confusing set of red lines. Career stability often means forfeiting research agendas that touch on local and sensitive politics. Self-censorship can be more effective than state censorship within academia.

As part of the workshop, we identified a number of strategies for researchers working in the region to employ to protect their research agendas, their networks, and their ability to be full partners in collaborative research.

- Strategy 1: Create horizontal platforms for your work, collaborating with colleagues inside and outside of the region. Having some visibility through alternative publication platforms (including blogs and web-based outlets) and visiting affiliations can broaden the career horizon.

- Strategy 2: Negotiate access when outside projects seek partners. If you are joining a larger survey project, request additional questions that inform your independent research as a condition of support. Likewise, condition your support on the ability to inform the research findings and to be a collaborator on equal footing.

- Strategy 3: Protect your identity and that of your research contacts. Parachuting researchers are eager for introductions, but there is a difference between being helpful and doing the groundwork for someone else. If you are a researcher starting in a new environment, be sensitive to creating daisy-chain networks and allocate sufficient time in your research project to build your own contacts.

- Strategy 4: Create mentor and door-opening relationships, and return the favour. Reciprocity is the key to successful research collaboration.

- Strategy 5: Seek relationships with funders and anticipate their funding priorities and how your research can fit their parameters. Acknowledge all sources of support in publications. Transparency in funding helps colleagues know where to look and ultimately builds collaborations (not zero sum competition).

Models of collaboration allow for flexibility to include new partners throughout a grant lifetime. For example, as part of our Arab University Collaboration project (funded by the Emirates Foundation at the LSE Middle East Centre) we have tried to include small research fellowships to be disbursed during the grant cycle to bring in new work by early career researchers by application. In that way, new networks emerge and new work gains support at early stages.

When projects fail and funding is pulled, there may be an opportunity to understand broader political movements in action. Detail and document your experience and trace the institutional lines of support (and repression.) In the upheaval of revolution, war and neighboring crisis, many local researchers may underappreciate the immediate ethnography of political transition. Understanding how institutions like universities, ministries and civil society organisations react to regional change is like peeling an onion. The direct cause is often impossible to identify. Instead, we find that a closing of political space (and research opportunities) often occurs as self-preservation and caution on the part of administrators, without direct instruction or state censorship.

Our hope is that by building upon a small network like the APSA MENA Fellows Program, we might create a broader interest in the field on how to build sensitive collaboration projects that have long-term commitments to a community of scholars inside and outside of the region. With this interest in mind, we must combine a healthy respect of a wide field of political science that includes multiple methodological approaches and styles, and prise the expertise of the country-based experts.

Karen Young is a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. She was research fellow at the LSE Middle East Centre from 2014-15, where she remains a visiting fellow. From 2009-14, she was assistant professor of political science at the American University of Sharjah (UAE).

Other memos from the workshop

- Sarah Parkinson ‘Towards an Ethics of Sight: Violence Scholarship and the Arab Uprisings’

- Evren Balta ‘Researching the “Unresearchable”: State Politics and Research Ethics in the MENA Region‘

- Guy Burton ‘Teaching Practices of Middle East Politics: Potential and Challenges‘

- David Mednicoff ‘Religious Identity and Social Science Research in the Middle East’

- May Darwich ‘The Challenge of Bridging Disciplines and Area Studies in Teaching the Middle East‘

- Nermin Allam ‘Embodied Scholars: The Insider-Outsider Status of Researchers in Field Work’