by Andrew Delatolla

Recently there has been increased discussion on statehood, the modern state, and sovereignty framed by the events of the 2011 Arab Spring, the Syrian Civil War, and the weak state in Iraq. Indeed, there is no lack of scholarship on the state in international relations, political science, sociology, and development studies, and the research available is far reaching: whether it is focused on discussions of government and regime type, electoral systems, constitutions, governance, state institutions, state formation, and what, exactly, the state is and is not.

Critically, much of the often-cited scholarship on the state and statehood is written from Western perspectives and developed from histories and theories of Western and European state formation. This has created knowledges constructed from a distinctive set of histories that have been generalised to apply internationally. These knowledges include the typological description of the state: weak, failing, and failed; and, related to state typologies, practices of development and state-building that seek to fix the state. Although these knowledges and practices are employed with good intent with the aim to build strong and competitive global partners, uphold liberal norms and values, develop civil society, enrich state-society relations, and democratise state institutions, the burden of these knowledges and the employment of these practices are embedded in histories of colonialism and imperialism.

While these histories of colonialism and imperialism may seem like matters of the past given the temporal discontinuity between colonial Europe and the global present, many post-colonial states are still dealing with the consequences of this history. Instead, the history and story of colonialism has created a continuity for the post-colonial state that is apparent in state institutions, social relations, anti-colonial and anti-imperial politics, the modern state, and enduring global hierarchies. These enduring knowledges and practices from colonial eras subject the modern state in the global peripheries to the language of weakness and failure, requiring socio-political pacification through development and state-building; a cyclical phenomenon of intervention, weakness, and intervention.

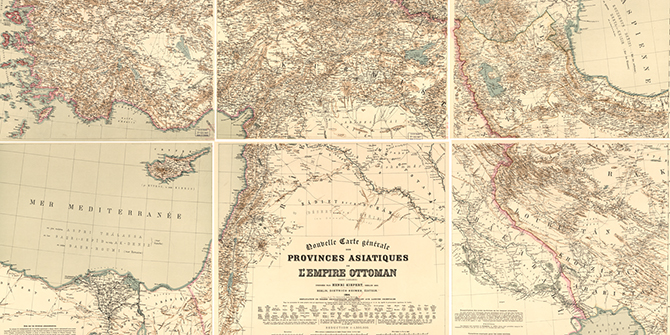

Arguably, the construction of institutions for governance, the coercive restructuring of society and networks of authority, and the impact of a globalising economy have reinforced lopsided structural relations in the modern state, which inevitably produce weakness. By examining the history of the modern state in Lebanon and Syria, for example, contemporary state weakness can be tied to stories of Ottoman imperialism and European colonisation through the persistence of traditional and constructed practices of governance.

By separating the traditional and constructed practices of governance it is possible to examine the ways in which they become attached, producing unintended consequences. The advent of the modern European worldview of scientific progress, rationality, and Christian secularisation influenced the interactions between European representatives and Ottoman subjects and the Ottoman administration in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This modern worldview tempered perceptions of the other through sectarian and racist categorisations; packaged anew into ideas of civilisation and progress. For example, the French and Russian delegates within the Ottoman Empire were quick to develop local allegiances with portions of the population based on religious affiliation. The French, despite their demands for the secularisation of the Ottoman Empire, institutions, and laws, developed an allegiance with the Catholic communities, offering economic benefits and political and physical protection. The French viewed it as a right to protect the ‘Christian civilisation’, the ‘only true religion’, against the fanatical Muslims. This language is used throughout the French correspondence between the successive French governments in Paris and the French consuls in the Ottoman Empire. The Russians, on the other hand, for similar reasons, viewed it as their ecclesial right to protect the Orthodox Christians from the oppressive Ottoman forces.

The prominence of scientific racism was not only discursive, it was also enacted through pressure exerted by European powers on the Ottoman Empire to modernise and bind the institutions of governance to secular principles, such as that of ethno-religious equality, and emphasise centralisation of governance as a rational method to control the populations. The idea was that the creation of modern institutions of governance would eliminate the need for irrational and uncivilised economic and political practices of nomadic tribes, family networks, and the separation of personal law from imperial law. In doing so, the very networks of authority that had been crucial to the sustainability of social, political, and economic life had been altered; changing the balance between communities and providing new political appointments to fight over, which, in turn, politicised the populations in new ways and deepened ethno-sectarian conflict.

However, as much as the European states pressured the Ottoman Empire into promulgating reforms based on European knowledges and practices, the Sublime Porte recognised the need for institutional development and centralisation to compete with European global hegemony and survive within the new international state system. Arguably, the European powers and the Sublime Porte had a similar goal: to modernise the institutions of the Ottoman Empire, but the means and methods to which change would be promulgated created tension between the two.

Nevertheless, over this period, state institutions and social order were transformed to bring the Ottoman Empire into a European styled modernity. As interactions between the Ottoman Empire and the European powers increased, ideas from the European period of Enlightenment began to take hold within sectors of the population and the administration of the Sublime Porte. These ideas took on a distinct form that sought to salvage Islam as the imperial bedrock of the Ottoman Empire, but also create a national identity that altered the state-society relationship from subject to citizen. The amalgamation of Western ideas of nationalism and rational governance with principles derived from interpretations of Islam and imperial governance were dismissed by European consuls, who thought it necessary for the Ottoman administration to reform by casting away the traditional knowledges and practices of Ottoman governance. Nevertheless, from this amalgamation of ideas came a distinct form of Ottoman nationalism that pushed for constitutional reform, and with it emerged a series of oppositional and local forms of nationalism, such as pan-Arabism and nationalisms the promoted ethno-sectarian self-determination, which sought political and territorial secession from the Ottoman Empire and/or the European powers.

Similarly, development and state-building practices are embedded in attempts to modernise the institutions that are perceived as unmodern and inefficient, with the aim to rationally order society by creating new socio-political practices and knowledges. Like practices of colonialism and imperial modernisation, effective development and state-building employs force to pacify rebellious and determined populations; creating new insurgent knowledges and practices.

The concept of the state and statehood have, again, become a central concern to public political discourse and the social sciences. With this increased awareness there has also been a continuity of pervasive knowledge in these discourses centred on the Middle East, whether it is through the language that frames the ‘War on Terror’ and government policies which determine what refugees are worth saving, or research that perpetuates ideas of conflict based on civilizational schisms, including the question of whether Islam is compatible with democracy. In various ways, these discourses and concerns are rooted in assumptions of Christian and Western civility in opposition to Islamic fanaticism. It has since become important to have these discussions on the state and statehood, but even more so, to revisit the multiple histories and conceptions of the state and statehood, to recognise the global dynamics that have reproduced a set of knowledges and practices, though with good intent, but often having broader negative consequences.

Andrew Delatolla is a final year doctoral candidate in the Department of International Relations at LSE. His research interests include sociological perspectives on state formation, state building, and development with particular focus on 19th and early 20th century Turkey, Lebanon and Syria. Andrew tweets @a_delatolla.

Andrew Delatolla is a final year doctoral candidate in the Department of International Relations at LSE. His research interests include sociological perspectives on state formation, state building, and development with particular focus on 19th and early 20th century Turkey, Lebanon and Syria. Andrew tweets @a_delatolla.