by Sara Masry

![By Women2drive (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/files/2017/10/WOMEN2DRIVE_logo.png)

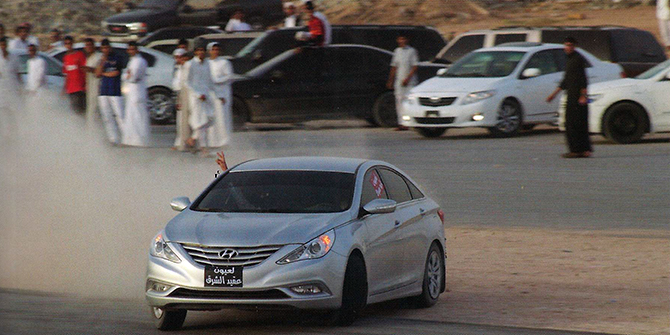

Saudi men and women have – for the most part – been rejoicing on social media channels since a royal decree repealing the ban was announced on 26 September. What has been conspicuously missing, however, is any extreme backlash from the conservative core of society – the expectation of which having been regularly touted as one of the main reasons for keeping women away from the steering wheel. Who can forget some of the clerical establishment’s most shame-inducing arguments against women driving, gems like the warning that driving will ‘damage women’s ovaries’ or ‘lead to adultery’? Or, just this month, that women are incapable of driving because their brains are ‘a quarter the size’ of men’s, as judged by a cleric who has thankfully since been relieved of his duties. Despite the existence of these viewpoints in the country, there have nonetheless been no discernible popular movements opposing the decision to lift the ban. Conservatives have in the past publicly opposed Saudi government decisions – particularly when it comes to women’s rights reform.

During the 1960s, when the late King Faisal and his wife, Iffat Al Thunayan, attempted to introduce female education to Saudi society, they were met with staunch resistance from tribal leaders and their cohorts. Throughout the country, the idea of women participating in the public sphere and receiving formal schooling sparked untold fear among clerics and average people alike. Eventually, and not without great efforts from activists for female education, mainstream society came around. That being said, the consent of religious scholars was only secured by guaranteeing certain conditions, mainly relating to the curriculum and environment of girls’ education.

More recently, internal tussles revolved around the issue of women’s employment. During the reign of the late King Abdullah, a series of reforms were instituted intending to increase the percentage of women in the workforce. A law introduced in 2006 mandating that women’s clothing and cosmetics stores should be staffed by women took until January 2012 to be implemented due to intense lobbying from the religious establishment, which opposed the concept of female shopkeepers coming into contact with male customers (that women would obviously still be buying their lingerie from male store clerks seemingly left the clerics unfazed). In 2010, clerics called for the boycott of supermarket chains that employed female cashiers, and the Council of Senior Scholars, Saudi Arabia’s highest religious authority, issued a fatwa declaring it religiously impermissible for women to work in places where they would mix with men. As with female education, the grumbles eventually died down, and the taboo surrounding working women has all but disappeared from Saudi popular discourse. According to official figures, the percentage of Saudi women in the private sector increased from 12 to 30 percent between 2011 and 2017.

It should be noted here that domestic opposition to women’s rights reform has not been the sole domain of men. Saudi women have time and again come out in support of some of the policies that limit their freedoms. In 2010, a women-led campaign entitled ‘My Guardian Knows What’s Best for Me’ garnered 5,400 signatures on a petition that demanded punishment for activists calling for equal rights between men and women, including an end to the guardianship system. Nonetheless, while this may not have been the tipping point leading to its reversal, women have been at the forefront of intermittent campaigns to end the ban since the 1990s – and have paid the official price for it in lashes, jail time and exile. Many of these activists, including Manal al-Sharif and Aziza al-Yousef, rejoiced at the news of last week’s royal decree.

Others joining the chorus of celebration included the Council of Senior Scholars. They came out in strong support of the ruling, despite the same institution’s former stalwart resistance to women driving. Saudi newspapers, in tandem, praised the move as a historic step. Social media channels were flooded with celebratory messages and memes that, while sometimes featuring simplistic jokes regarding female drivers’ allegedly negative impact on road safety, for the most part reflected jovial reactions to the shift. Given the fact that conservative elements have traditionally stood in the way of anything furthering women’s autonomy, does this mean that they have liberalised their views overnight? There are a number of potential explanations for the lack of a visible backlash in this case. One factor is the very low threshold of tolerance for dissent in the country, particularly as the government is in the midst of implementing wide-ranging reforms primarily designed to restructure the economy and develop some of the country’s core service sectors. Many have fallen foul of state strictures, with a number of recent arrests of both public critics and simply those who have not adequately expressed support for state policies. In such a climate, it is difficult to fathom public displays of disapproval akin to those witnessed at the advent of female education or employment – although this hasn’t prevented some reservations and resistance being expressed on social media channels.

Another major factor is the growing youth bulge in the country, with over 50 percent of the population under the age of 25. Hundreds of thousands of those have received their higher education in relatively progressive societies like the UK, US and Australia since the King Abdullah Scholarship Programme was launched in 2005. Moreover, the Saudi populace is one of the most digitally-connected globally, with undeniable implications for local attitudes – both in terms of greater exposure to worldwide trends, as well as access to those with diverse viewpoints and backgrounds in a society that had hitherto been relatively atomised and fragmented. True, there may not necessarily be quantifiable links between such phenomena and social liberalisation. However, a number of studies have shown that young Saudis are increasingly fascinated with different cultures and ways of life, as well as more prepared to question dominant narratives. While the underlying traditions and family values remain unchanged, Saudi millennials are virtually unrecognisable from their forebears.

There is of course the question of the limits of tolerance towards these changes from the more radically religious elements of Saudi society – those who for all intents and purposes have been socially conditioned to believe that, among other tenets, women must be shielded from the public sphere. To be sure, in 1979, when some such elements felt uncomfortable with the pace of change and purported ‘westernisation’ of Saudi society, a rebel group led by Juhayman al-Otaibi, a member of a prominent Saudi family, laid siege to the Grand Mosque of Makkah in a two-week operation that led to hundreds of deaths and the government’s implementation of an austere Islamic social code in the aftermath. While a reversal of state liberalisation policies appears unlikely as Saudi Arabia surges forward with its Vision 2030 developmental programme, the stakes are far higher today, with the potential for transnational extremist groups to take advantage of internal disgruntlement and radicalise individuals in a country that has hitherto been a bastion of traditionalist socio-cultural regulations. While the lack of concerted resistance thus far towards women driving may in part speak to a more progressive and younger Saudi society, it would be remiss to assume that those opposing such policies have disappeared from view altogether.

Sara Masry grew up between the UK and her native Saudi Arabia. She holds an MA in International Studies and Diplomacy from SOAS, and another in Iranian Studies from the University of Tehran. She previously worked as the MEC’s centre administrator, and is currently a Middle East analyst at a London-based consultancy, Stroz Friedberg. She tweets at @Sara_m_90

Sara Masry grew up between the UK and her native Saudi Arabia. She holds an MA in International Studies and Diplomacy from SOAS, and another in Iranian Studies from the University of Tehran. She previously worked as the MEC’s centre administrator, and is currently a Middle East analyst at a London-based consultancy, Stroz Friedberg. She tweets at @Sara_m_90

7 Comments