by Charles Tripp

This article is part of a collection of tributes to the late Faleh A. Jabar.

There was so much to admire about Faleh as a person and a scholar. And for those who did not have the good fortune to know him personally, his scholarly qualities live on in the works that are key parts of his legacy. It is through his ideas and arguments that we can appreciate the contributions that he made to the understanding of Iraqi history and society, and of the larger processes that have played themselves out in the distinctive setting of Iraq.

I know that my own work has been influenced not only by the great wealth of information contained in Faleh’s writings, but also by his approach and method. He helped to situate Iraqi developments in a comparative field, but, equally importantly, he examined systematically and critically the very categories whereby social and political action has been commonly understood in Iraq. In some respects, Faleh pursued a research agenda that engaged seriously with the latter part of Karl Marx’s famous statement in the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte that ‘men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please…’ where Marx continues, ‘precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honoured disguise and borrowed language’.

With significant critical qualifications, this could stand for the ways in which Faleh addressed himself to puzzling out the weight and significance of the categories that have been used to ‘explain’ Iraqi society and its political struggles. Thus, in his writings he has tackled head-on Shi’i identity and politics, Islamism more generally, tribalism and ethnic nationalism. All have been used in deeply troubling ways by analysts and actors within Iraq and beyond to provide explanations, but also to justify various political positions. Faleh did not dismiss their relevance as frames for understanding aspects of the political in Iraq, but sought to understand the combination circumstances that made them so potent at certain periods of Iraqi history.

He achieved this through a method that he called ‘conjunctural’ – a method that he admired in others to whom he freely and generously acknowledged his debt in turn. This meant taking into account the kinds of forces that shaped Iraqi society and the political imaginations of Iraqis. These were not unique to Iraq, in the sense that capitalist transformation, the logic of the modern state, and the nationalist imaginary were radically changing much of the world from at least the eighteenth century onwards. However, it was the particular conjuncture of these forces in the Iraqi context, working upon pre-existing formations of Iraq’s heterogeneous population and creating new ways of living and interacting that interested him.

For Faleh, this did not lead to a conventional structuralist, determinist account of modernisation and development. Far from it. Instead, he saw this as requiring him to decipher the mentalities that made social and political action meaningful by seeing the world through the eyes of the political actors. These were not ciphers. They were people who possessed agency and who made choices in often difficult circumstances, sometimes with disastrous results. It was a mark of the richness of Faleh’s approach that he could provide an empathetic understanding of how people saw and acted upon opportunities, whilst at the same time retaining a dispassionate view of the ideological forces that fired them up.

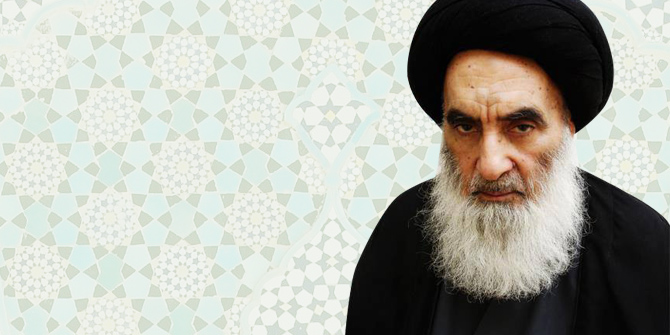

Faleh’s work on Islamic political and economic thought in Iraq and beyond brought out the ways in which he saw the Islamist movements as distinctive, but also analogous to movements in other parts of the non-Islamic world. Examining the works of Ayatollahs Muhammad Shirazi or Baqir al-Sadr, he took their ideas seriously on their own terms, but was also alert to those factors in Iraq at the time that combined to make those ideas so influential. For him, Islamism was not a cover for something else, but this did not mean that was unaware of the kinds of things people try to get away with under the guise of religiosity.

Having witnessed the tumult of Iraq’s modern history, he could see the potency of moral certitude at a time of flux and insecurity. Indeed, as he acknowledged, it was the failure to appreciate the depth of such insecurity that led some to fall back on doubtful culturalist explanations when trying to account for the undoubted power of religious beliefs in politics. Free from the romanticism that has sometimes been implicit in subaltern studies, Faleh tried to work out why people saw themselves, their interests and their leaders in the ways they did. But he was equally inquisitive to know how the leaders framed their projects, believing them to be influenced by the same processes as those they claimed to lead. This applied to the varied and disputatious leaders of sections of the Shia of Iraq that he captured so exactly, as well as to the clansmen of Saddam Hussein’s entourage and their ideological pretensions.

In the universe of conjunctural developments, Faleh reminds us that it is important to understand what kinds of opportunities, as well as immediate threats, present themselves to the actors concerned. Their actions shape the institutional landscape in which markers of identity and difference become themselves objects of competition, as struggles develop to assert what it means, for instance, to be Shi’i in Iraq. The great variety of answers that have arisen over the years ensures that this designation must be the object of study as a field of political conflict, and cannot therefore in itself be a sufficient explanation of such conflict. This was a key project at the heart of Faleh’s work. We remain indebted to him for having devoted such skill and creativity to its development, providing a series of authoritative accounts of the constituent elements of Iraq’s political society – accounts that drew not only on sociological method, but also on historical and political imagination, and particularly on an ability to get the measure of those Iraqis who have collectively and individually given definition and substance to its political field.

Charles Tripp is Professor of Politics with reference to the Middle East at SOAS, University of London, and a Fellow of the British Academy.