by Ghoncheh Tazmini

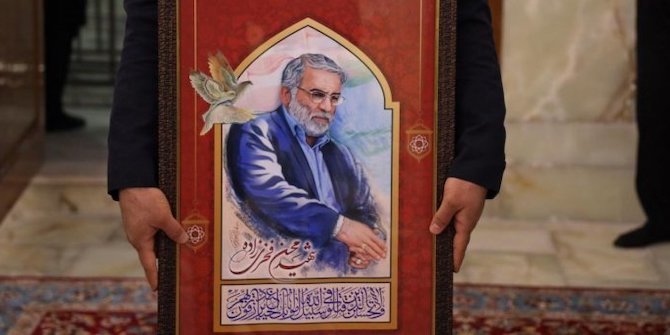

The assassination of top Iranian scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh has intensified debate in Tehran over whether to reengage in the nuclear deal with the incoming Biden administration. Tehran alleges that the US was aware of what it holds, was another Israeli-sponsored act of terror intended to derail any chance of diplomacy with Washington. Iran has indicated that it may retaliate. However, if we are to go by the events that followed the assassination of General Qassem Soleimani in January 2020 – after the initial shock – Tehran will likely revisit the idea of renewed nuclear talks.

Biden’s imminent investiture in January 2021 has raised hopes of renewed dialogue with Iran. However, a substantive and enduring breakthrough – one that cannot be derailed so easily with such acts of sabotage – requires a complete overhaul. Diplomacy can only be achieved if the US adopts a new political logic of pluralism as the appropriate framework for engaging Iran. Pluralism in the international system is founded on the belief that each state or political model has to resolve its own challenges, and that historical experience cannot be transplanted from one context to another.

If Iran’s anxiety over the covert transfer of norms and institutions through regime destabilisation or military confrontation is mitigated, the entire political ecosystem of Iranian foreign policy could see a fundamental transformation. With fears of regime overthrow neutralised, Tehran may be more willing to revise its regional policy, and even curb its ballistic missile defence program. Most importantly, pluralism in the international system could foster pluralism domestically, making Iran less of a threat to the US and its allies.

If Iran’s sense of insecurity is mitigated, it may lead to a less securitised state and allow civil society to develop, while making room for more progressive social reforms. There are indications that the leadership may be open to this.

Contrary to the view that the Iranian power system is an immutable and unchangeable force, Iran has quietly made important amendments to a range of judicial and legal policies. These reforms are not implemented by a particular political party or a figurehead that articulates and orients an overarching reformist agenda, as in the Khatami days. They are, however, ongoing, regular and woefully under-reported in the international media. Adaptive and autonomous, Iran’s modernisation ‘from below’ is as an ongoing process of interaction between universal value patterns and specific cultural codes. Several policy changes stand out and I chart these below.

For instance, on 16 October 2020, Chief Justice Ebrahim Raisi signed an edict called the ‘document on judicial security’, outlining stipulations to increase judicial transparency, to prevent torture and forced confessions, to stop the use of solitary confinement and to safeguard the rights of defenders in court. A week earlier, Iran saw a watershed in women’s rights: the conservative Guardian Council announced that women could run for president after having been barred for more than four decades. Meanwhile, there are reports that Iran is experiencing its own ‘#metoo’ movement, with women going public about harassment incidents, with indications that the Iranian leadership is responding to accusations with punitive measures.

There is also new legislation protecting children. In June 2020, Iran passed a measure criminalising emotional or physical abuse and child abandonment. The measure also expands legal protection offered to children and juveniles. The law, now known as ‘Romina’s Law’ materialised largely in response to outrage over the murder of a teenage girl by her father a month earlier. The new law also sets heavy fines and jail time for parents that prevent children from getting an education. Judiciary and security officials are also legally obliged now to report cases of child abuse and to place children under protection services.

In December 2019, human rights campaigners secured the approval of a law allowing Iranian mothers who are married to foreigners to pass on their citizenship to their children. Children born to a foreign father were previously unable to work or access healthcare. In November 2021, the first children out of some 10,000 received their Iranian identity card, known as a ‘Shenasnameh’.

There was another step towards equality in October 2019, when Iranian women watched the country’s national team for the first time in over 40 years. This followed the death in September of Sahar Khodayari, who set herself on fire to protest against her arrest for trying to get into a match. In June 2019, the country implemented another measure towards reducing gender discrimination when Iran’s Supreme Court upheld a law that mandated equality in ‘blood money’ compensation – no longer would a woman’s compensation be worth half of a man’s.

Other progressive measures include the way the government is addressing alcohol addiction, which it sees as a public health crisis rather than issue of morality or legality. In January 2019, Iran announced it would open a further 100 alcohol rehabilitation facilities in the country. Iran also saw a milestone for minority rights: in July 2018, the Zoroastrian Yazd city councillor Sepanta Niknam was reinstated in his post after a 9-month suspension. New legislation passed by the Expediency Council allows religious minorities to run in municipal elections. The bill overrides the Guardian Council’s rule that a non-Muslim cannot be a member of a body that makes decisions in Muslim-majority constituencies.

Since November 2017, the judiciary has halted most executions of individuals convicted of non-violent drug offenses. In January 2018, the Iranian judiciary suspended the execution of 5,000 inmates. In April 2018, parliament passed an amendment commuting the sentences of many of the 5,000 people on death row for drug offences. There is an ongoing nationwide debate over compulsory hijab in the car, and over what is considered private or public, with an IRNA (Iran’s News Agency) article asking ‘Private or not private?’ to prompt a legal and religious discussion about private space within cars. Mohsen Gharavian, a prominent cleric, argues that a car is private property, while the police for example, insist it is public and subject to screening.

Pluralism as a framework for relations in the international system has its own inherent value. Its practice abroad begets the same at home: pluralism in the international system could allay Tehran’s sense of insecurity and have a knock-on effect on Iranian internal politics. A thaw in relations is unlikely to be achieved solely through the easing of sanctions or a revised nuclear deal – such an arrangement could easily be decertified again. By engaging Iran with a new pluralistic framework, the US and indeed the international community would be supporting this undercurrent of reform, and the complex dialectic between state and society that has yielded these important changes.

I’m from Iran

its very sad that you let this published on your website,

Iran is a dictator regime which kills and murmuring people,

a few days ago they executed Rohollah Zam just because he was publishing news on his channel on Telegram,

this article obviously part of regime’s propaganda .

why don’t you mention that a few month a go regime executed someone for drinking alcohol?

each year in Iran there are more execution, 2 years ago in protests regime of Iran killed over 1500 people, according to Reuters, you call it reform?!

Please don’t help this regime to kill more people by publishing these fake information!