by Frederic Schneider

The separate Emirati and Saudi Hyperloop projects exemplify how nation-centric current infrastructure planning in the Gulf is, and how regional megaproject competition is helping nobody. The GCC needs to be more committed to economic integration and political coordination, which can be boosted by reviving and updating the ailing Gulf Railway venture.

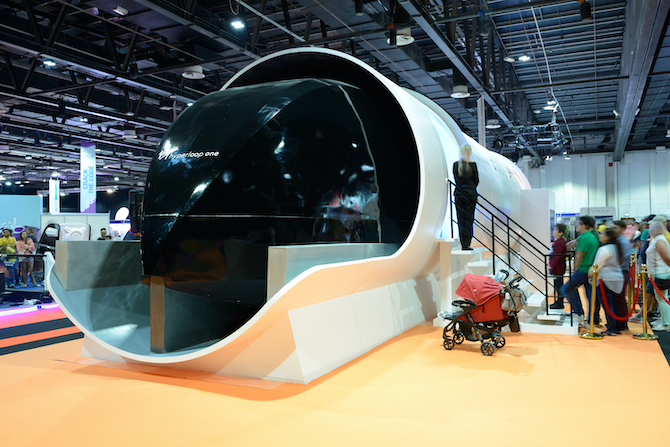

The Hyperloop

Ecstatic early plans foresaw that 2021 should have seen passengers board the world’s first Hyperloop to travel between Abu Dhabi and Dubai. Yet the future of the connection between Abu Dhabi and Dubai is uncertain; the project is currently not listed on the Virgin Hyperloop One website. Harj Dhaliwal, the company’s managing director for the Middle East, floated other possibilities in 2019, including a Hyperloop connection between Dubai International and Al Maktoum airports. Meanwhile, plans have emerged for a Hyperloop in Saudi Arabia.

However, nothing tangible beyond some Memoranda of Understanding have emerged so far, and critics doubt the concept is technically or economically viable. And even if the Abu Dhabi-Dubai line materialises at some point, the line may cause more traffic problems than it solves without proper public transport infrastructure in the terminal cities. In other words, there is a good chance the Emirati Hyperloop will end up being of little more use than a glorified commuter rail service, as has previously happened to the Shanghai Transrapid.

The Hyperloop concept (and high-speed rail in general) is more useful for longer distances, such as the envisioned line between Los Angeles and San Francisco (about 600 km) or the maglev connection under construction between Tokyo and Nagoya (about 300 km). As luck would have it, these distances are close to those between the GCC’s major centres, for example: Kuwait City–Manama (about 400 km), Riyadh–Doha (about 600 km), Abu Dhabi–Muscat (about 500 km). Combined with an ideal topography along the Gulf coast (no mountains, no rivers), a high-speed rail project that links all major GCC centres looks like a perfect way to achieve regional economic integration.

The Gulf Railway

As it happens, the GCC had plans for just such a project, the Gulf Railway. The diesel-driven line from Kuwait to Muscat was optimistically planned to open in 2018. Whether the new date, 2023, is going to happen is more than questionable, although there is some construction. The lack of progress is in large part due to sustained economic problems. On top of that, the general preference of individual countries for national prestige projects (such as the Hyperloops in the UAE and Saudi Arabia) over regional cooperation reveals the lingering political rifts and economic tensions within the GCC.

However unclear the future of the Gulf Railway currently is, the importance of this connection is only going to increase, especially with short-haul flights becoming more and more incompatible with Gulf countries’ goals of limiting CO2 emissions. The current plans are for diesel-powered trains because the line will include both passenger (at 220 km/h) and freight services (at 80-120 km/h). While diesel is optimal for freight trains, dual usage will pit passengers and freight against each other for limited capacity and constrain the passenger train speed.

But passenger trains run faster on electrified tracks. Conventional electric high-speed rail would increase the speed to about 320 km/h, a maglev system like the Chuo Shinkansen would clock in at about 500 km/h, and a Hyperloop reaches 1,000 km/h (at least theoretically). Thus, adding a dedicated, electrified high-speed passenger line to a diesel-powered freight line would both free up capacity for freight and make passenger travel much faster and more attractive. Add to this the symbolism that passengers will be riding electric trains (100 percent solar-powered) instead of fossil fuel-powered trains.

Using available technology also means more secure planning and better cost control. It would also be an affordable project. A conventional high-speed rail like the French TGV or the German ICE costs roughly $20 million per kilometre to build, about the same magnitude as a multilane motorway. Such a connection would connect Kuwait City with Muscat in 5 hours. A maglev variant would probably be about twice that price tag but cost less in maintenance, especially in a sandy desert environment.

Reviving the Gulf Railway project will also become even more useful with a further regional expansion of rail connections. One such envisioned project, ‘Tracks for Regional Peace’, was proposed by the Israeli government to link the seaport of Haifa with the Gulf, although the current political tensions will likely relegate this vision to the back burner.

Forging Lasting Links

Dreams of flying drone taxis and Hyperloops are spectacular and futuristic, but they also turn out to be lofty and elusive. In the end, the success of ambition is not measured by artist’s impressions but by tangible, practical results. The most clear-eyed infrastructure plan consists, thus, of reviving the lacklustre plans for the Gulf Railway and augmenting them with a dose of proven, cutting-edge high-speed rail technology – such as TGV or even the maglev Shinkansen. This will avoid both the shortcomings of a pure diesel solution for passenger travel and the distant mirage that is the Hyperloop.

Most crucially, such a project would refocus policy on regional collaboration and cooperation. Each GCC country alone (even Saudi Arabia) is too small to face the global post-oil economy alone. If they want to thrive, if they want to be ‘the next Europe’, as Mohammad bin Salman proclaimed, they must stop their destructive, internecine competition and bundle their resources instead, and integrate both politically and economically. The GCC will celebrate its 50th anniversary in 2031. What better symbol of unity than a truly visionary, joint megaproject that links the region’s centres?

1 Comments