by Margarida Bandeira-Morais, Simona Iammarino and M. Adil Sait

The concept of economic complexity, first introduced by Hidalgo and Hausmann (2009), postulates that it is possible to infer knowledge and capabilities within countries through their ability to export competitive products that are both diverse and ubiquitous relative to the rest of the world. The associated Economic Complexity Index (ECI) has since grown in popularity as a way of predicting countries’ economic growth, income inequality, human development, among other macroeconomic outcomes.

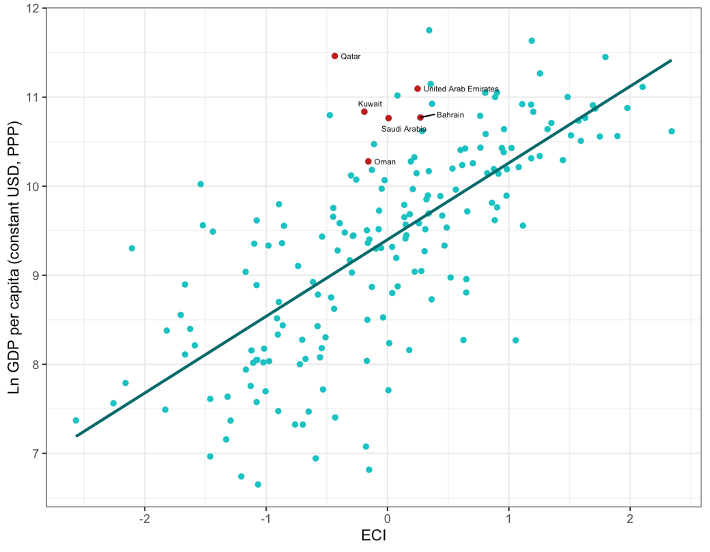

In a review of the literature from the past decade, Hidalgo (2021) argued that the strong predictive power of the ECI in explaining long-term economic growth suggests that a country’s complexity level pins an equilibrium income level. Hidalgo further maintains that the direction of this relationship is from economic complexity to income growth, rather than the opposite, and that it would be somewhat improbable that countries with relatively low complexity given their income – such as Qatar, Oman, Bahrain and Kuwait, among others – will increase their complexity in the future (Hidalgo, 2021). The implication of this argument is that these economies would grow less than other countries with similar GDP per capita, reverting to a lower ‘equilibrium’ income level in line with their ECI measure.

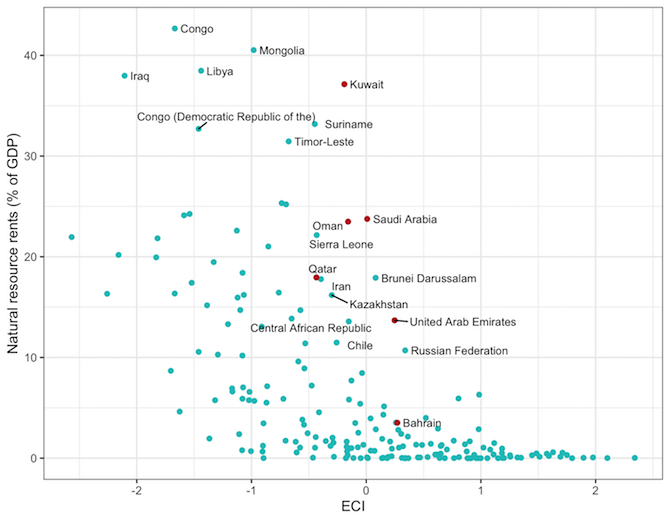

In parallel, Canh, Schinckus and Thanh (2020) estimated that economic complexity has a significant negative impact on total natural resource rents, and argued that focusing on improving economic complexity could help lessen the dependence on natural resource wealth. A strong negative relationship is found for upper-middle- and high-income countries – the latter group including Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) together with other economies that have long moved away from relying on natural resource exports. Canh et al.’s results, however, may be biased by pooling countries that are very different in nature, because of reverse causality between natural resource rents and economic complexity, and by the fact that the analysis did not include oil revenues.

We argue that these studies, to a different extent, tend to disregard the specific context and unique characteristics of natural resource-dependent countries. Important questions remain over whether the economic complexity concept and method can be meaningfully interpreted in all contexts or rather as a ‘big picture’ empirical regularity that should not be relied upon for finer-grained or specific analyses aimed at informing policy-making. Our study focuses on economic complexity in the GCC region – with particular emphasis on the case of Kuwait – and examines the validity of employing the ECI in the area, using data from the Atlas of Economic Complexity (AEC) and the World Bank.

Here we report preliminary descriptive evidence. Figure 1 plots the strong positive correlation between the ECI and income per capita, showing that the GCC countries have lower economic complexity than expected for their income level, as Hidalgo alluded to.

Figure 1: ECI and GDP per capita across countries, 2017

Turning our attention to natural resources, Figure 2 shows that GCC countries are marginally more complex than other, mostly developing, countries with similar levels of natural resource rents, showing the expected negative relationship between natural resource rents (as a percentage of GDP) and levels of economic complexity. Kuwait stands out, as it displays the highest level of natural resource rents within the GCC group and, at the same time, a higher ECI than every other country with over 30 percent of their GDP originating from natural resources.

Figure 2: ECI and natural resource rents across countries, 2017

In addition to its higher level of natural resource rents as a share of GDP, Kuwait experienced larger oscillations in the ECI value over the period from 1995 to 2017 than the other GCC countries. To further understand the case of Kuwait and what may be driving the ECI fluctuations over time, we take a closer look at the country’s export data used in ECI calculations.

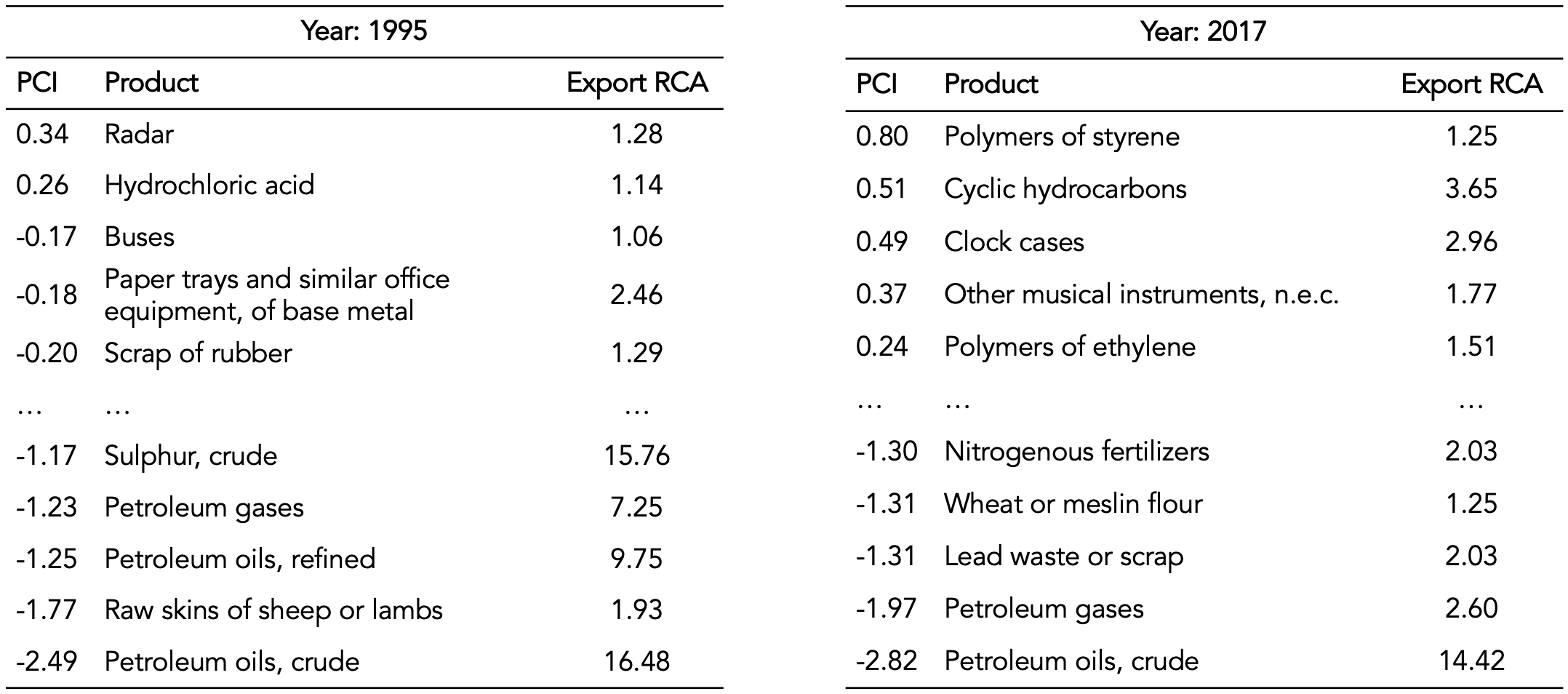

Diversity, one of the two key variables behind the ECI measure, is simply the total number of products which a country exports competitively relative to the rest of the world in a particular year (i.e. Balassa’s Revealed Comparative Advantage, RCA index, using a threshold of 1). Our preliminary analysis indicates that Kuwait’s diversity has seen strong variations over the period from 1995 to 2017, seeing a sharp decrease between 2005 and 2010, which coincides with the sharp decline of the ECI.

However, looking at diversity in isolation does not tell us much about the types of products Kuwait is exporting competitively. The Product Complexity Index (PCI, calculated for products analogously to the ECI for countries), reported in Figure 3 for the initial and final year of the observed period, suggests that changes in economic complexity levels experienced by Kuwait appear to be driven by oil-related goods’ shifts, particularly in terms of a drop in the relative complexity of such products. The reason for this needs further investigation, though it is likely due to shifts in world export patterns and the way in which the ECI and PCI are calculated. This points to some limitations of the complexity indicators in the case of natural resource-dependent economies, since in ‘absolute’ terms there is no reason to believe that the capabilities needed to produce oil-related products (or their ‘complexity’ level) suddenly decreased only for a limited number of years, relative to all other products.

Figure 3: PCI in Kuwait, 1995 and 2017, top and bottom 5 products with RCA>1, ordered by the PCI (ranging from about 3 to -3 with average 0).

Overall, our preliminary findings seem to raise some questions about what exactly the complexity measures ECI and PCI capture for Kuwait and GCC countries (and more generally natural resource-dependent economies). Our ongoing analysis aims to ascertain whether and to what extent economic complexity has any predictive power for the outcomes of interest in GCCs, e.g. economic growth, once we control for oil exports and other key covariates.

This is part of a series on the possibilities and obstacles for economic growth, exports and diversification in the GCC states, based on contributions from participants in a closed LSE workshop in June 2021. Read the introduction here, and see other pieces below.

In this series:

- Exports, Diversification and Economic Growth by Kendall Livingston

- Economic Complexity and Exports: Kuwait in the Context of the GCC Region by Margarida Bandeira-Morais, Simona Iammarino and M. Adil Sait

- Growth in the Gulf: Four Ways Forward by Frederic Schneider

- The Role of Economic Complexity in Increasing Exports and Growth by Anis Khayati

- Beyond Oil: Have Manufactured Exports and Disaggregated Imports Contributed to Economic Growth in Kuwait? by Trevor Chamberlain and Athanasia Stylianou Kalaitzi

- The Nexus Between Export Diversification, Trade Openness and Economic Growth in the UAE by Saima Shadab

- Export-Led Growth in the UAE: Causality Between Non-Primary Exports and Economic Growth by Athanasia Kalaitzi, Samer Kherfi, Sahel Al-Rousan and Maria-Salini Katsaiti

- Reaching for the Stars: How and Why do the Gulf States Aim to Transform Their Economies to ‘Knowledge-Based Economies’? by Martin Hvidt

1 Comments