by Esther Meininghaus and Carina Schlüsing

‘I see many foreign fighters who settle here, marry, divorce, and remarry, accumulate money and even open shops. You came here for jihad, right? Good. Why don’t you go to the front? Why are you opening a shop?’ – Layla, a doctor in Maaret al-Nouman, cited in Voices of Idlib, Crisis Group 2018

While war is being waged, fighters form an inherent part of everyday life of local communities. ‘Fighters’ are not isolated, but always also neighbours, husbands, or shop owners – thus they are inseparably intertwined with ‘civilian’ life, which is transformed through their presence.

We argue that translocality as a concept allows us to shed new light on a twofold process: how armed groups anchor themselves in and across local communities. This aspect matters for the communities and because understanding the translocal dimension of war is a prerequisite for grasping processes of alliance making and fragmentation at different scales. Over the last decade, social science research has put enormous efforts into analysing and understanding the causes, dynamics and outcomes of such fragmentation (e.g. Walther, Leuprecht and Skillicorn 2020; Bakke, Gallagher Cunningham and Seymour 2012). In search for explanations as to why some armed groups show greater cohesion and can better avoid fragmentation, we hypothesise: armed groups that are locally anchored as well as connected through well-functioning linkages across localities are more likely to persist and avoid fragmentation.

Translocality as a Concept

By locality, we refer to a concept as well as an empirically observable fact: that is, the knowledge or consciousness a person has of a physical place and the ways in which communities in this place function (Appadurai 1995). We can imagine a neighbourhood as a site where locality is produced. In the neighbourhood we grew up in, we know its streets and alleyways, perhaps the apartments, houses and gardens of those we know closest – that is, its physical place. However, we also are aware of its social relations – the friendships, perhaps enmities, or familial relations of our parents, siblings, friends, or neighbours. Besides the building of houses or the fencing of fields the knowledge and imaginations shape a neighbourhood (or social space). Following Arjun Appadurai, the techniques which are used to name places, or how agriculture is performed, change over the course of years and decades, which explains how locality has a spatio-temporal dimension; it is not ‘fixed’, but in the constant process of being made (Massey 1993).

To define translocality, we refer to the interconnectedness of localities. Porst and Sakdapolrak (2017) understand translocality as ‘processes and practices producing local-to-local relations and thereby enunciate[ing] the simultaneity of mobility and situatedness in specific places’ [emphasis added by authors]. Yet, we would add, Appadurai’s original understanding of locality is decisive here in that it considers the interweaving of place, social relations, knowledge and imaginations. Translocality draws our attention to the micro-and meso-level (differing from transnationalism, which tends to be used for macro-level analysis). It is particularly fruitful to understand differentiation within – seemingly – one and the same armed group in close or distant, yet in every case distinct localities. In sum, translocality is both an empirically observable fact and a concept of how actors and researchers intersubjectively ‘know’ a place and space. While the concept initially emerged out of cultural anthropology, geography and migration studies (Etzold 2016; Greiner and Sakdapolrak 2013; Brickell and Datta 2011; Appadurai 1995), our concern is to introduce the concept to the study of war – and peace.

Local Anchoring and Translocal Linkages

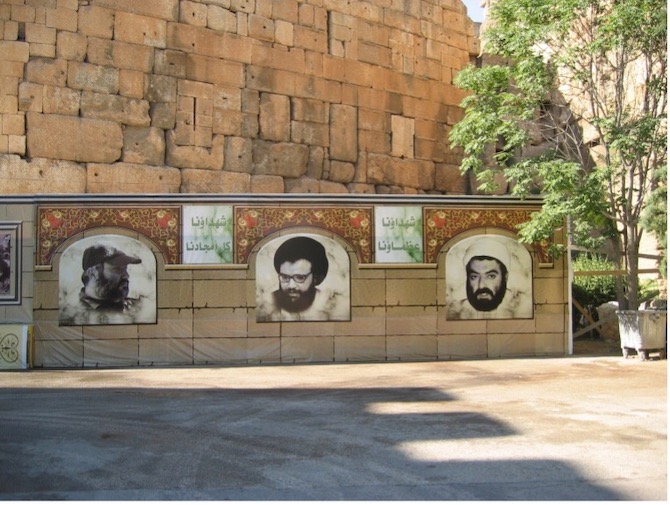

As one example within Syria, we could think of Lebanese Hezbollah, which was founded in 1982 and entered the Syrian war in 2012 to provide training for Syrian pro-regime fighters, with the aim to crush the pro-democracy movement. Rather than integrating Syrians into its battalions, Hezbollah has created Syrian branches since 2014 that are translocally linked, stretching as far as from al-Qusayr in Syria’s west to Deir al-Zur in the east and Aleppo to the north. Despite being an ideologically Shi’a Islamist organisation, Hezbollah’s aim to take roots in local communities has led it to recruit Syrian Sunni fighters. Its presence has transformed local communities through marriage and trading ties in Syria, but it has also been party to ethnic cleansing, whereby local demographies have been altered. For example, the population of the area around the Sayyida Zaynab shrine in Damascus under Hezbollah control has become largely Shi’a-dominated under its influence, doubling to approximately 150,000 since 2011. Hezbollah framed the shrine as a site requiring protection, rendering it a symbolic centre especially for the prayers of fighters. It has thus also reshaped its meaning in local consciousness.

Similarly, while intense fighting tied up regime forces on other fronts, the pro-Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its armed wing, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), fostered the declaration of an autonomous region of Rojava in northern Syria. It did so by rapidly fortifying previously existing armed structures provided by the Union of Communities in Kurdistan (KCK) umbrella that the PYD (like the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, PKK) had been part of. Through these ties, resources, personnel and ideology were mobilised. Also, from 2003 onwards, the PYD built on longstanding local social networks that had initially been activated by the PKK in northern Syria from 1979–98. The declaration of Rojava’s establishment and de facto provision of security for Kurds constituted a significant improvement because it allowed for political, cultural and language expression that Kurds had previously been denied for decades. Importantly, however, this control-taking triggered both approval and disapproval within the population and across localities: while some localities welcomed it, in other places local residents took control of checkpoints themselves to prevent a PYD presence (Allsopp 2015, 210). While support for the PYD has traditionally been stronger in some localities (like Afrin and Kobane) than in others (such as Jazira), also within these, the degree of local anchoring across villages varied.

Translocality Matters

A translocal analysis thus highlights the ties between armed actors and communities as well as the significant differences that exist across localities. The analysis of intertwinement between translocal and local structures is important to understand not only the enabling effects of strong trans-ties but also local differentiations and political fragmentation among actors and society in competition for power and representation. When armed groups become powerful locally, they contribute to newly emerging hierarchies and long-term changes to physical place, social space, and imaginations of meaning. Armed actors shape localities while equally, localities shape the emergence of armed groups.

A translocal perspective allows us to see how fighters are embedded in local communities through their personal ties. It shows the need to differentiate between a core organisation (Hezbollah, PKK) and local branches, which vary from one locality to another despite strong command structures, and it explains processes of cohesion and fragmentation. Translocality as a concept emphasises how the changes we observe can be temporary or persistent, but they cannot simply be reversed and are not exceptional cases. The often-practiced emphasis on external influences (for example the role of Iran) tends to neglect knowledge on how local entrenchment and transformations within communities occur, although these shape the everyday lives of communities so decisively.