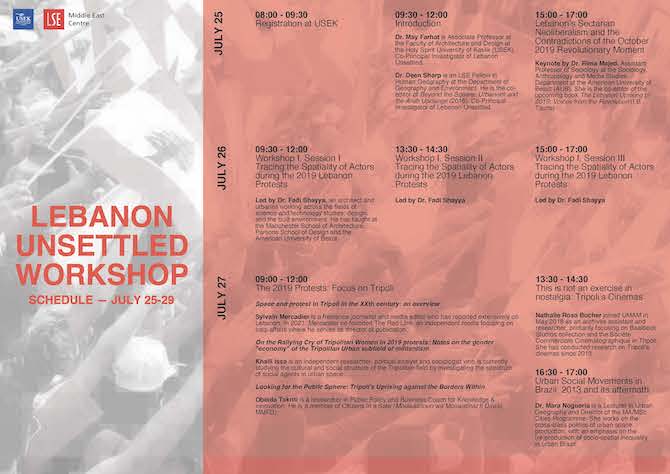

by Deen Sharp, May Farhat, Fadi Shayya, Maria Bassil & Marc El Samrani

On July 25, 2022, as part of the Lebanon Unsettled project, we held a four-day workshop (25-28 July) at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK), and a final day in Beirut to visit UMAM: Research and Documentationand Beit Beirut. This workshop brought together graduate students to think about the socio-spatial implications of the Lebanon October 2019 protests and their broader historical context and impact. Dr Deen Sharp (LSE) and Dr May Farhat (USEK), the co-principal investigators of Lebanon Unsettled, began the workshop by explaining the significance of studying the protests. Sharp stated protests are key to how social change happens and shape the definition of what can be said to be possible in political and social life. The city, Sharp stressed, and the intricate material and social networks that shape and surround it are equally crucial for protests to happen. During the 2019 revolt, protestors reshaped the social meaning of cities and urban space. The protest was a critical moment in shaping struggles over collective consumption, identity, the use of urban space and how people relate to the city. It is these concerns that we focused this workshop on, subjects that continue to be struggled over in Lebanon.

Dr Rima Majed, Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, delivered the opening keynote on ‘Lebanon’s Sectarian Neoliberalism and the Contradictions of the October 2019 Moment’. Presenting her framework of “sectarian neoliberalism”, Majed stressed that the financial crisis that started to escalate in the summer of 2019 was central to driving people to the streets. The crisis, Majed argued, was in part the result of the historical political-economic model of sectarian neoliberalism. Majed outlined the importance of highways to the protest, to “stop work” and bring the country to a halt. And how this also meant people gathered in various spaces throughout the country to protest, “the geographical scope was unprecedented.”

Analysts have frequently commented upon the geographical breadth of the 2019 protests, its decentralised and geographically comprehensive nature. While Beirut was the epicentre of the protest, protests erupted across Lebanon’s cities, towns and in-between spaces (such as highways). This was a central theme that we, as workshop organisers, wished to unpack and explore further. The selection of USEK (20km north of Beirut) as a partner university for this project meant the students engaged in the workshop all came from outside of the capital, from areas such as, Jounieh and Batroun, as well as Mount Lebanon. All the graduate students took part in the protests and their engagement during this period often focused on spaces outside of the capital, for example, along the Zouk highway or in their hometowns.

Two mapping workshops formed the centre of the week for the participating graduate students to map and archive the different geographies and spatial practices of the uprising. Dr Fadi Shayya led the first session entitled, ‘Intimate Legacies: Tracing the Spatiality of Actors during the 2019 Lebanon Protests’. Grounded in Actor-Network Theory, this exercise asked participants to trace their spatial-autobiographical journey during the 2019 Lebanon Protest. Students traced how they found out about the protest, how they first decided to go to the streets, how they negotiated their complex social legacies and ties (kinship, sect, institutions, and technology) and how they appropriated urban space as part of networks (human, nonhumans, environment, systems, and attachments). They remarked on how it felt to be part of the uprising, what they did to protest and how different it was from media representations. The outcome was a set of relational-intimate-spatio-temporal-socio political mappings that reflected on interrupted flows, compressed time, bodily traumas, multiple realities, sturdy/fluid alliances, and emergent spatial practices.

In the second workshop, led by USEK graduates and doctoral candidates Maria Bassil and Marc el Samrani, students were asked to create a common performative map. This map focused on space and the 2019 protests, and how this social movement affected collective identity in Lebanon. Bassil and el Samrani worked with the students to share their personal urban experiences of the protest and its impact on their spatial understanding of the city. The common map embodied these experiences that in turn created a new way to engage and map the spatial traces of the 2019 protests.

A critical element of the mapping workshops was to think about 2019 historically and methodologically. We engaged students extensively with the idea of the “archive” and what it means to write history from it. Dr May Farhat remarked upon our key methodological strategy in Lebanon Unsettled was to situate the 2019 revolts not in post-Civil War Lebanon or in relation to the Civil War itself; but in relation to deeper historical moments, such as the Ammiyat, a notable set of revolts focused on Mount Lebanon in the 1820s and 1840s. The aim was to teach students how deeper historical moments can inform the revolts of the present.

Students reflected upon and undertook through their mapping exercises the creation of a live archive of the 2019 protest. They also participated in interviews about their experiences of the 2019 revolt and its historical and geographical significance. These interviews will be collated into a website as part of the Lebanon Unsettled project and launched at the start of 2023. Students also engaged with institutional archives. USEK provided an official tour of their newly expanded Special Collections and Archives. We also visited the archives established by UMAM: Documentation and Research in the southern suburbs of Beirut. UMAM is an NGO founded in 2005 by Lokman Slim and Monika Borgmann. Slim was assassinated in 2021. Students also got to engage with how UMAM archived the 2019 protest.

By introducing the participants to the archives at both USEK and UMAM, as well as engaging in creating their own archive for the 2019 protest, we asked them to think about: whose voices are archived and how, the types of material that are considered worthy of archiving, and the different approaches of archiving and sorting information taken by UMAM and USEK.

At the end of the five days, the students reflected on what they have learned. Students noted how concepts like “sectarian neoliberalism” enabled them to understand the historical context of the protests and banking crisis, and how the focus outside of Beirut meant they saw 2019 from a very different perspective. Nearly all the students remarked that they see 2019 as a moment of hope in an otherwise increasingly bleak context. “We actually need to continue to reclaim what is ours as citizens, it is not only about the power and the state, but it is about the people,” one student concluded. “And this is the time when we need to rethink the spaces we live in and the conditions we live, not only to claim our basic rights but beyond that. What we look like as Lebanese people and as a contemporary Lebanese society.”

This piece is part of the research project ‘Lebanon Unsettled’ conducted in collaboration with the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK) and part of the LSE Middle East Centre Academic Collaboration with Arab Universities Programme, funded by the Emirates Foundation. Deen Sharp is the principle investigator on this project with May Farhat.

1 Comments