by Ghenwa Hayek

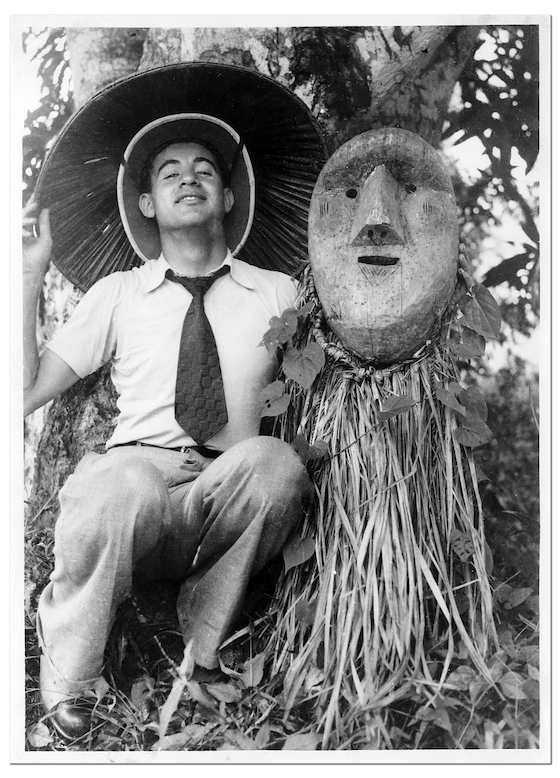

While most of my colleagues in our collaborative academic project ‘Arab News Futures’ examined the present and future landscapes of Arab media, my intervention involved the future as imagined by two Lebanese journalists – Abdullah Hsheimeh and Kamil Mroue. Both travelled across colonial West Africa in the 1930s and documented their journey in travel memoirs, Naḥnu fi-Ifrīqiya (Us in Africa,1938) and Riḥla fi-Bilād al-Zunūj (A Journey Through the Negro Homeland, 1931). I used these texts as a lens and perhaps a reminder that this is not the first generation to worry about its future, or the future of the nation, and highlight discussions of how journalists’ portrayals of contemporaneous migrant communities in diaspora allowed them space to negotiate the future of their not-yet-born nations with their compatriots and with colonial authorities.

As they travelled across West Africa in the 1930s, the Lebanese journalists Hsheimeh and Mroue reflected on – and worried about – their nation’s future. Although it is not often thought of, travel writing can be an introspective genre, and while both wrote about their adventures traversing the continent and visiting the Lebanese across West Africa, they also worried about Lebanon. Both sensed that the French mandate – established in 1920 with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire – was coming to an end (a fundamental promise of the Mandate, which was ostensibly designed as a temporary rule before these former Ottoman provinces – now-countries – reached independence). As they looked around them at currently colonised countries in West Africa, they sensed that colonialism would also, one day, end. And of course, not too far off in the distance, they picked up the noise of war being prepared across Europe. So, in many ways, these travel accounts are stories of their anxious times, a time in which it felt like many parts were moving and not all of it in the right direction. The men projected their worries onto the page, using their writings to advocate for the independence of Lebanon and promote their vision of what that future Lebanon could look like.

The writers also feared that the young generation born in diaspora would not want to return. For example, Hsheimeh wrote about the “lines drawn on the foreheads of fathers and mothers whose stay under the skies of this land has extended, as they spoke to me about the future of their children…if they are unable to return to the homeland (218)”. They worried that the local authorities were helping the Lebanese grow attached to Lebanon and wrote that upon their return, migrants are assumed to be wealthy and are manipulated by friends and family members into spending their money on useless projects. Mroue warned his fellow Lebanon-based compatriots against treating these returning immigrants like “dairy cows,” and scolded them for treating them like “American tourists” (111). Instead, migrant money should be channelled into development, banks and businesses that could help the country thrive. The journalists worried that a large part of the population is being left out as more and more people depart from Lebanon: “Who will be left?,” they openly wondered. They compared Lebanon and the Lebanese favourably, if enviously, to West Africans, considering themselves more deserving of independence and the end of Europe’s iron grip than other people.

It is a bit unnerving to read these musings projecting Lebanon’s future from the 1930s. Of course, the Mandate ended, and some version of the independent Lebanon Mroue and Hsheimeh imagined came about. Mroue, in particular, helped shape that future Lebanon in the media, going on to write for an-Nahar and then to found al-Hayat, one of the premier pan-Arab newspapers of its time (he was assassinated in the headquarters of the newspaper in 1966). And yet, their worries about migration, about the state of the nation, and about dependency echo the concerns of Lebanese people today, albeit in media and on a scale, I doubt either man could have envisioned.

This piece is part of a series on the idea of the future as it relates to Arab media and cultures, based on contributions from panellists in an LSE research symposium in May 2022. Read the introduction here, and see other pieces below. For more on the LSE Academic Collaboration project with the American University of Sharjah, ‘Arab News Futures’, see here.

In this series:

- ‘The Future in Arab Media and Cultures‘ by Omar Al-Ghazzi & Abeer Al-Najjar

- ‘The Soviet Union as ‘Future’: the Socialist Imaginary of Arab Intellectuals during the Mandate Period‘ by Sana Tannoury-Karam

- ‘Visiting Lebanon’s Future in its Past‘ by Ghenwa Hayek

- ‘Historians and the Future: Abdallah Laroui’s Prescriptions for a Recovered Moroccan Modernity‘ by Idriss Jebari

[To read more on this and everything Middle East, the LSE Middle East Centre Library is now open for browsing and borrowing for LSE students and staff. For more information, please visit the MEC Library page.]

that true