by Frederic Schneider

Dubai competes with its regional rivals Abu Dhabi and Riyadh for top spot in the Gulf for financial services. Source: Michaela Loheit, Flickr

The UAE plans to transition to a ‘competitive knowledge economy’ with a ‘first-rate education system’. According to its Vision 2021, the country will become ‘the economic, touristic and commercial capital for more than two billion people by transitioning to a knowledge-based economy, promoting innovation and research and development, strengthening the regulatory framework for key sectors and encouraging high value-adding sectors’. The government ‘seeks to place the UAE among the top countries in the world in income per capita and ensure high levels of national participation in the private sector workforce’.

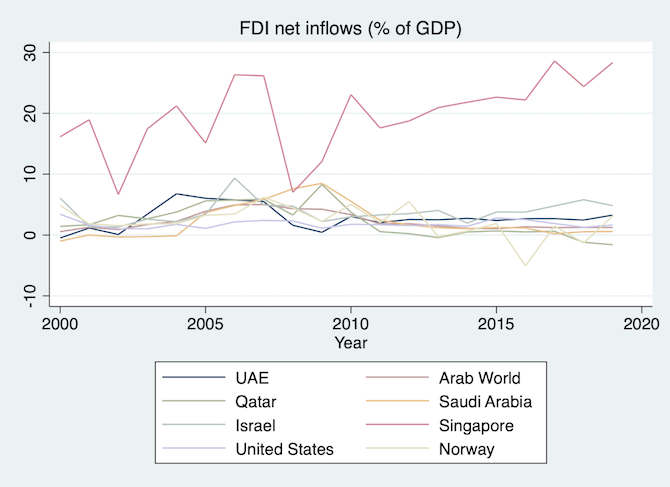

The Vision defines key performance indicators for these goals, including output per capita, net inflow of foreign direct investments, innovation and education rankings such as TIMMS and PISA. Yet these indicators look grim; for example, GDP per capita is almost half of Norway’s and only two thirds of the US or Singapore. Why is that?

A Quick Tour

Construction industry: While some projects, like the Burj Khalifa, have been economic and branding successes, there is a massive and growing oversupply in office and apartment space due to an over-optimistic ‘build it and they will come’ strategy. Moreover, construction as an industry is unsuitable to increase the economy’s labour productivity.

Tourism: Visitor numbers have stagnated since 2017, yet areas for hotels and tourism will grow even further. In addition to oversupply, there is growing regional competition, especially from Saudi Arabia, and the fundamental problem of limited labour productivity. Although the country focuses on the luxury segment, tourism productivity is middling (10 percent of the workforce produce about 10 percent of GDP).

Transport and logistics industry: Growth potential seems exhausted; the empty Al Maktoum Airport and declining numbers of containers at Jebel Ali again indicate oversupply. Here, too, we see intense regional competition, not least within the UAE itself with Etihad Airlines and the new Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi.

Financial services: Flourishing in the UAE, particularly with the Dubai International Finance Centre. But again, growth potential is limited as evidenced by stagnating FDI inflows and a lacklustre performance on the local bourses and a couple of prominent de-listings. And, again, we see fierce competition in the region, most notably with Abu Dhabi’s Global Market and Riyadh’s King Abdullah Financial District.

In short, we see common problems like intense regional rat races, oversupply, saturated markets and low labour productivity. In the following part, I outline four ways to adjust Vision policies and put the UAE back on the path to growth and post-oil prosperity.

1. Reanimate Regional Integration

GCC countries are in fierce economic competition with each other. Instead of competition through creativity and quality, we see (sometimes brute-force) competition of almost identical ideas, institutions, technologies and projects. This duplication is costly and inefficient, especially in areas where there can only be one winner such as the world’s tallest building or the regional transportation hub. Moreover, many projects are driven by prestige, not economic utility. These are high-visibility, high-risk moonshots that are often forgotten soon after they are announced.

These rat races make losers’ investments unproductive and the lack of regional cooperation means the GCC miss out on economies of scale which would arise from countries pooling their resources. Instead of these wasteful wars of attrition, Gulf governments should focus on economic cooperation and integration and specialise in areas where each country has a local comparative advantage.

A good example of this are the two parallel space agencies in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which could be efficiently combined into a regional agency akin to the European Space Agency. Or take as another example the prestige race for the first Hyperloop between the UAE and Saudi Arabia, two parallel, yet similar, long-shot projects of limited economic use. Instead, GCC governments should come together and revive a languishing project to unite the countries physically and symbolically with a passenger and freight rail network.

2. Commit to Education and Research

The region needs to invest in human capital to transition successfully to a knowledge economy with highly productive workers. Yet education is stagnating despite being a professed priority for Gulf countries: the UAE’s federal budget for education has declined in real terms over the past 14 years and will take another 8 percent cut in 2021; subpar pre-K and K-12 schooling leaves students unprepared for university; federal universities are beset with inexperienced and frequently changing administrators; PhD programmes are minuscule and there is no federal institution for higher education and research like the American National Science Foundation. The result is a dearth of high-impact research at universities or private businesses, especially in comparison to R&D-driven economies like South Korea’s.

To solve this problem, there needs to be a concerted push to make the promise of ‘first-rate education’ a reality and create a haven for R&D-heavy economic activity. This means making education (pre-K, K-12 and higher education) the highest budget priority, professionalising university administrators and establishing a well-funded national institution that organises research activity, funds grants and prizes, endows research professorships, national laboratories and PhD programmes and coordinates regional and global research collaborations.

3. Reduce Institutional Uncertainty and Political Risk

Economic activity, particularly foreign investment, depends on a stable and predictable regulatory environment, transparency of the political process and confidence in the rule of law. The UAE has accomplished this by adopting the special economic zones paradigm and a string of laws and regulations that make the country a regional safe haven.

But, as the examples of money and gold laundering allegations show, it is not problem-free either and the legal environment can be challenging to navigate as it is constantly changing. More importantly, the country is held hostage by the Gulf’s (geo-) political turmoil and the resulting discount that long-term investors apply to the Dubai and Abu Dhabi stock markets. Neighbour Saudi Arabia, in particular, stands out with scandals like the Khashoggi murder, human rights violations, purges and the Yemen war that is swashing across the border.

To make foreign investors feel more at ease, GCC members must get serious with their plan of building a ‘high-performing government that is effective, transparent and accountable ’, as stated in Saudi Vision 2030. In addition, a less antagonistic approach to foreign policy and a dedication to dialogue and de-escalation in the region will have a soothing effect on the region’s financial markets.

4. Acknowledge the Changing Social Contract

Finally, there are fundamental societal changes underway. The current social contract is paternalistic. The ruler owns the land and natural resources, manages them with wisdom and foresight for his subjects and takes care of their well-being through comfortable public sector employment and generous welfare, including housing, pensions and healthcare.

But the looming end of natural resource wealth will end this social contract and bring instead increasing public debt, unemployment, reduced welfare and the spectre of taxation. The anti-austerity protests in Oman show citizens’ incomprehension of and discontent with these changes and are a sign of things to come.

In parallel, Gulf governments are weaning their citizens off cushy but costly public sector jobs and trying to funnel them instead into productive private sector occupations. Despite these tawteen policies, citizens remain largely unprepared due to lacking skills and having a rentier mentality that comes from an education that raised ‘entitled patriots’. The Gulf’s youth bulge further compounds the employment problem and underemployment of young khaleejis will remain a problem for the coming years.

Finally, GCC countries, and particularly the UAE, are enacting policies such as golden visas, naturalisation of expatriates and changing the weekend from Friday-Saturday to Saturday-Sunday to attract expatriate knowledge workers. This strategy risks generating divisions and discontent among nationals.

These dramatic changes necessitate an open societal discourse about the post-oil model for society and honest communication about the future of the welfare system, taxation, the productive role of citizens in the economy, national culture and nationals’ status relative to expatriates and naturalised citizens. However, rulers need to anticipate that citizens might want something in return for the changed world they are entering.

What Next?

The economic problems of the Gulf countries are real and imminent and current policies need to be adapted to return to growth. These include: (1) reviving the Gulf Cooperation Council with useful, realistic and collaborative projects that foster economic and political integration; (2) a fundamental change of policy priorities towards education from pre-school to PhD, including a massive increase in public funding, administrative reforms of higher education and the founding of a federal research and science organisation; (3) administrative reforms and foreign policy efforts that reduce institutional uncertainty, increase transparency and attenuate (geo-) political risk in the region and (4) an honest dialogue about the future form of the post-oil social contract.

This is part of a series on the possibilities and obstacles for economic growth, exports and diversification in the GCC states, based on contributions from participants in a closed LSE workshop in June 2021. Read the introduction here, and see other pieces below.

In this series:

- Exports, Diversification and Economic Growth by Kendall Livingston

- Economic Complexity and Exports: Kuwait in the Context of the GCC Region by Margarida Bandeira-Morais, Simona Iammarino and M. Adil Sait

- Growth in the Gulf: Four Ways Forward by Frederic Schneider

- The Role of Economic Complexity in Increasing Exports and Growth by Anis Khayati

- Beyond Oil: Have Manufactured Exports and Disaggregated Imports Contributed to Economic Growth in Kuwait? by Trevor Chamberlain and Athanasia Stylianou Kalaitzi

- The Nexus Between Export Diversification, Trade Openness and Economic Growth in the UAE by Saima Shadab

- Export-Led Growth in the UAE: Causality Between Non-Primary Exports and Economic Growth by Athanasia Kalaitzi, Samer Kherfi, Sahel Al-Rousan and Maria-Salini Katsaiti

- Reaching for the Stars: How and Why do the Gulf States Aim to Transform Their Economies to ‘Knowledge-Based Economies’? by Martin Hvidt

thanks for sharing the great information on Growth in the Gulf.

thanks for sharing the great information on Growth in the Gulf.

Thanks for sharing this informative blog with us. This blog has excellent insights and knowledgeable content.

Keep posting.