by Nour Albrzawi

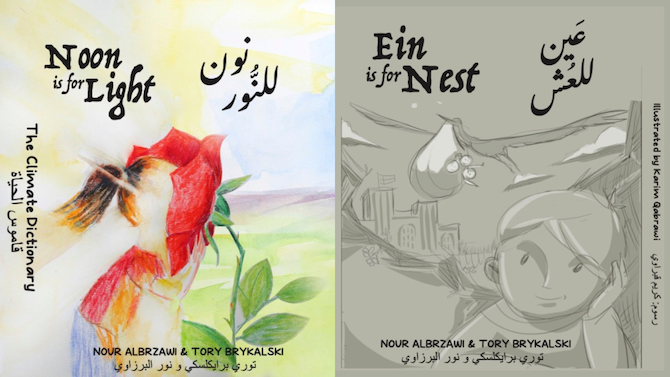

The Climate Dictionary is a children’s book series that invites English and Arabic readers to step into the flight paths and life cycles of Syria’s White Crane and Damascus Rose. The first two books, ع للعش (Ein is for Nest) and ن للنور (Noon is for Light), were inspired by the questions and desires articulated by Syrian refugee students living in Lebanon. Each book’s title is composed as the first letter of an Arabic concept and the concept in both Arabic and English. The books give a documentary view into the daily life of refuge-making and provide emergent vocabularies to help both refugees and climate activists make sense of their realities.

This series began in 2016 when anthropologist Tory Brykalski and I met at a language exchange program hosted by the American University of Beirut. Our conversation began around the question of ‘politics’ and whether it was possible to exchange ideas and translate experiences with each other. We immediately discovered that the etymological roots of the Arabic and English concepts of ‘politics’ were different. From 2016 to 2021, we used this discovery to observe the unfolding ‘crises’ in Lebanon and worldwide as manifestations of this difference. We wrote The Climate Dictionary as evidence that it is possible to unlearn ‘the enforced’ difference and write new meanings for what counts as ‘politics’.

As a refugee student and a teacher in Lebanon, I observed first-hand how the Lebanese state constructs an image of refugees to produce a particular kind of politics. On the one hand, this image excludes refugees from formal schooling; and on the other hand, simultaneously treats them as a humanitarian case in need of ‘saving’ by INGOs and the UN (#NoLostGeneration). The educational dilemma faced by refugees is that most states forbid students without certain forms of documentation from accessing education. At the same time, billions of dollars have been spent to help the Lebanese state integrate these refugee students. Academic and non-academic institutions have capitalised on this financial flow. They study misery by taking samples and conducting research on refugees to draw conclusions such as: refugees are violent ‘others’, an ‘epidemic’ , and responsible for many problems – including the pollution of rivers.

This educational dilemma is what we contemplated as I taught science to elementary schoolers and Tory taught social science to high schoolers. We started drafting the books in an effort to give an image of ‘the refuge’ that our students wanted. The process raised a question for us about the myth of inclusive education premised by hierarchical logics and the difficulty of identifying lessons from within the sciences and humanities in English that are not predicated on the exclusion of refugees as political agents. We arrived at the following questions: How can we learn and teach in conditions (climate) that treat us as an ‘epidemic’? What is the connection between climate change and the ‘refugee crisis’? What is climate and climate change from the perspective of those who are the most vulnerable to its consequences? Can we think and write about belonging, inclusion, and the production of free thought within regimes that treat refugees as political-environmental threats?

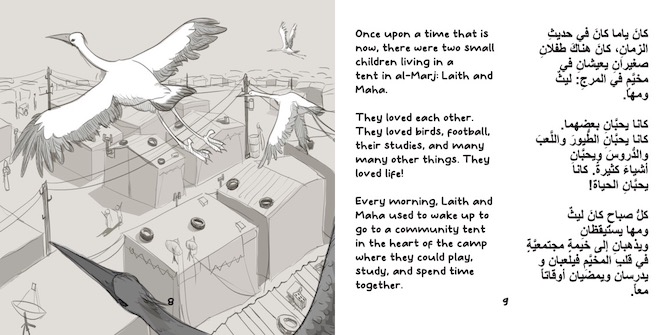

In the first book, Ein is for Nest, we connect the unnatural migration of Syrians to the White Crane via the figure of mother and emergency educator. Syria has historically been one of the favourite places for both women and the White Crane to nest. But the recent war and its impact on the land and environment has deprived families and birds of their ability to rest there. We conceptualise ‘migration’ here as a purely political action and analogise the movement of the human with the bird in order to connect our natural lives to our political bodies. This is necessary because increasing concerns about climate change and ‘the refugee crisis’ are deeply entrenched within an international order that requires the ontological separation of nature from humans. Within this order, the nesting practices of mothers and birds are devalued and separated from each other. Ein is for Nest presents a form of politics that integrates humans with their environment. We argue that Syrian migration is contingent on the war economy.

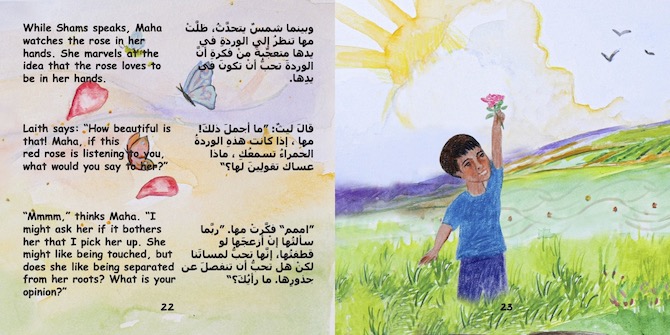

The second book, Noon is for Light, looks at the economy of Syrian refugees in Lebanon as a form of production and consumption that doesn’t fall under state policies or market mechanisms. The refugee practices an economics of survivance. This view was inspired by Salem al-Azouq, a farmer from Daraya who informed our character ‘Farmer Shams’, through the Damascus Rose farm that he established in the Bekaa Valley with the seedling ‘mothers’ he brought from Daraya. Survivance economies are based neither in subsistence realities nor in developmental logics. They are dependent on the nesting practiced by children and families, and on the light that drives their imagination and memory. The farm that al-Azouq co-created provided more than just matter; it provided empowerment, self-fulfilment, and belonging in a way that exceeds the limits of identity politics. We find his co-creation with Daraya’s roses to be an innovation to human’s relationship with the environment, pioneering our resistance to climate change by showing the characters Laith and Maha how to make a climate that is sustainable and meaningful.

The increasing anxiety about climate change ironically perpetuates it at the level of international relations of the different actors and policymakers dominating the discourse on climate action. Institutions cannot question the international order and its forms of production and consumption. Thus, their members rarely perceive the climate crisis as one of violence and war relations. Syria can be condensed as a representation of these relations: first, there is a genocidal regime that does not differentiate between humans, animals, and plants in its destruction of subjects; and second, there is a neoliberal regime that produces technocratic solutions to ‘the refugee crisis’ by perceiving refugees as ‘climate victims’. We argue that our climate is the result of our political, economic, and social war relations. Hence, it is not possible to speak about education in general, or climate change and action in particular without accounting for our life and the causes of refuge-making as the problem of relationality. Refuge, under this logic, is an economic or strategic fate. Societies that close their doors in the faces of refugees treat them as second-tier humans. The Climate Dictionary argues that we are part of the climate. We make the climate. Freeing us means freeing the climate.

In conclusion, The Climate Dictionary is one step forward in the production of a post-war children’s literature and thinking about a new meaning of climate ‘politics’. By finding alternative ways for not only Syrian refugees but refugees around the world to view education as a pursuit of rest and light, we argue that education ought to do more than just satisfy our curiosity. Education can also push us to think about ourselves as innovators and our lives as more than an epidemic.

[To read more on this and everything Middle East, the LSE Middle East Centre Library is now open for browsing and borrowing for LSE students and staff. For more information, please visit the MEC Library page.]