Last month, the UK government announced that it was freezing the BBC licence fee for the next two years and considering scrapping it from 2027. Here, UK Media Influence Matrix researchers take an in-depth look at BBC funding and the implications of the UK government’s proposals, while suggesting other options to explore. For more on the future of the BBC, come to our public event on 2 March, where BBC Director General Tim Davie will speak about ‘Public Service Broadcasting in its Second Century.’

The government’s announcement for BBC funding covers the six-year period from 1 April 2022 to 31 March 2028. The level of the licence fee will be frozen for the two years 2022/23 and 2023/24 at £159 before rising in line with inflation for the four years from 1 April 2024 to 31 March 2028.

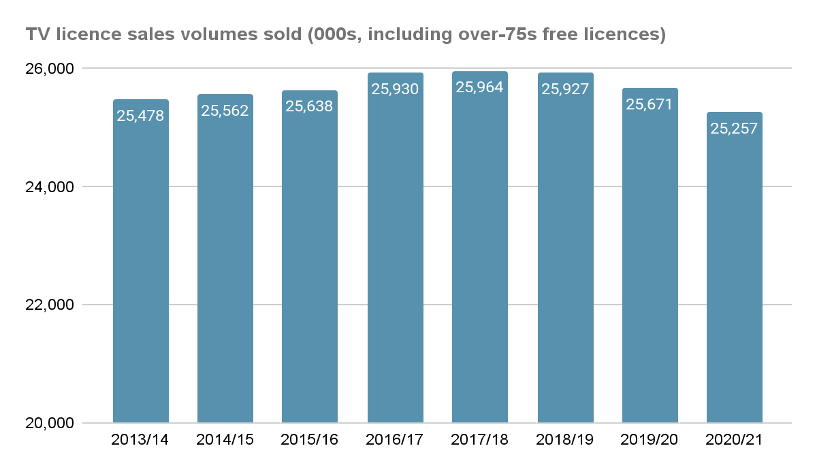

The size of the BBC’s real-terms funding shortfall will depend on two factors: (1) the rate of inflation between 2022-24 and (2) whether TV licence sales rise or fall. After growing for decades, TV licence sales have begun to decline in recent years and in 2020/21 stood at 25,257,000, 2.7% below their peak in 2017/18. TV Licensing, the body responsible for gathering payments, believes this is due to a rise in evasion, which has become easier as TV viewing moves online and both aerials and TV sets become unnecessary to watch live TV and catch-up TV.

Given that inflation is the highest it has been since 2008, the effect of the two-year freeze is therefore likely to be a substantial shortfall in BBC funding, which will be exacerbated if TV licence sales continue to fall. According to Enders Analysis, as of 2020 the BBC’s income had fallen 30% in real terms since 2010 and by 2027, given further below-inflation licence fee increases, the they estimate that BBC’s income will be 34% lower, some £1.4 billion per year, in real terms than in 2010.

Given that inflation is the highest it has been since 2008, the effect of the two-year freeze is therefore likely to be a substantial shortfall in BBC funding, which will be exacerbated if TV licence sales continue to fall. According to Enders Analysis, as of 2020 the BBC’s income had fallen 30% in real terms since 2010 and by 2027, given further below-inflation licence fee increases, the they estimate that BBC’s income will be 34% lower, some £1.4 billion per year, in real terms than in 2010.

Any cuts in provision as a result of the freeze is likely to be felt disproportionately by the poorest parts of the population. Some 8 million adults watch only free-to-air TV, 4 million of whom are in the C2DE demographic, and are therefore reliant on services like the BBC. As Enders Analysis recently concluded: ‘It is these people who will be hardest hit by real-terms licence fee cuts’.

Nadine Dorries’ arguments for freezing the licence fee

UK Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries has claimed that the freeze is justified by the need to protect households from the consequences of a licence fee rise:

The global cost of living is rising, and this Government are committed to supporting families as much as possible during these difficult times […] we simply could not justify putting extra pressure on the wallets of hard-working households.

Labour MP Lucy Powell challenged Dorries on the grounds that the licence fee is a small household cost compared to other soaring living costs, such as energy and household bills, about which the government is doing very little. If the government is genuinely concerned about the harm to family budgets of annual rises of up to £8 in the cost of the licence fee, then:

- Why has it done so little elsewhere in government policy to address the cost of living crisis or the 5 million people – 1 in 5 – who are in poverty?

- Why has the government removed the £20 uplift to Universal Credit, an estimated cut of £1,000 a year to the incomes of 4.4 million of the poorest households in the UK?

- Why not impose new taxes on the well-off to raise the £320m necessary to give free TV licences to the 2 million poorest households in the UK?

In addition, contrary to the impression some right-wing newspapers and MPs have given, TV licensing is not enforced by uniquely draconian methods, but by entirely normal mechanisms. It is important to note that criminal prosecution is only used as a last resort by TV Licensing in cases of repeated failure to pay and does not leave a criminal record that shows up in DBS checks. It also only results in a fine and in imposing the fine, magistrates are required to take into account ability to pay. Failure to pay the fine can result in measures being taken to recover the fine, but this is the same as with e.g. unpaid council tax, or indeed unpaid utility, phone or other household bills.

A more convincing rationale for the freeze, is that the Secretary of State is quite prepared to link BBC funding to how favourably she perceives the BBC to be covering the government.

Elsewhere in her Commons statement, Nadine Dorries argued that: “In the last few months, I have made it clear that the BBC needs to address issues around impartiality and groupthink.” Last October the Sunday Times reported that she had told allies: “Nick Robinson has cost the BBC a lot of money” by cutting off Boris Johnson during a Today programme interview. (She later denied having said this in evidence to the Commons DCMS Select Committee).

This is a blatant attack on the BBC’s political independence and yet an unsurprising one. So long as the government of the day has it within its power to periodically set the level of the licence fee and thereby influence the BBC’s single largest source of funding, ministers will face the temptation to use their power over funding to pressure the BBC.

The only way to end this is to change the way the BBC is funded. Either by:

- Establishing an independent commission to periodically review and determine the level of licence fee funding, or

- Replacing the licence fee with a new funding mechanism which guarantees the BBC a rising income and does not require periodic new settlements, or

- Both 1 and 2: a new funding mechanism, with the level of funding periodically reviewed and set by an independent commission free of government control.

The process by which the Press Recognition Panel was appointed is an obvious model for an appointments process free of government interference.

Sources close to Nadine Dorries told the Mail on Sunday that she intended to have abolished the licence fee altogether by the time the current licence fee settlement expires at the end of 2026. However, in her Commons statement she rowed back on this. According to the Financial Times this was because there was opposition within the Cabinet, on the grounds that there had not been a proper discussion on whether the licence fee should be replaced.

Key points and actions

What can we do to oppose these cuts to the BBC’s funding?

- Launch a petition declaring the public’s willingness to pay for public service broadcasting and to introduce funding measures that will avoid cuts to the BBC. In the short term, even a 5% rise in the price of the licence fee would only translate as an extra £7.95 a year, or an extra 63p per month. A petition is the ideal way to highlight this fact in a ‘viral’ way.

- Commission polling that compares support for a flat tax versus a progressive form of funding in order to take on board legitimate grievances about the shortcomings of the existing licence fee.

- Point out that relief for the poorest households paying for the TV licence could easily be organised: free licences for two million of the poorest households in the UK would cost £320m, equivalent to a range of small tax rises on the wealthiest UK households.

- Point out that cutting the BBC’s funding harms households across the UK, especially the poorest, in a different way: by forcing the BBC to make further cuts to its programmes and services. Many households cannot afford to subscribe to Netflix (£120 a year for the standard package), Amazon Prime Video (£96 a year), Sky (£312 a year or £492 with Sky Sports), The Times (£312 a year for a digital subscription) or The Telegraph (£156 a year). These households, as we have already argued above, depend on the BBC across TV, radio and online.

- Launch an Early Day Motion calling on the government to explore longer-term and fairer alternatives, such as a Household Levy (as in Germany) or an independently administered public service fee (as in Sweden) to the television licence fee, that maintain universalism as a fundamental principle of paying for genuinely independent public service media content.

This article is based on a briefing produced by researchers for the UK component of the Media Influence Matrix, set up to investigate the influence of shifts in policy, funding, and technology on contemporary journalism, funded by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. It produced its final report in December 2021 and will be preparing a series of briefings on media policy issues during 2022.

This article gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Callum Blacoe on Unsplash