New research shows how, across a range of measures, Britain has been undergoing a process of democratic backsliding since Boris Johnson became prime minister in 2019. Toby S James calls for a new Charter to reverse this erosion and rebuild the trust of citizens.

Boris Johnson’s “partygate” scandal had been framed as a test for British democracy. There was law-breaking at the highest level of government during a time of national emergency. Those in office responsible for making laws, broke the laws themselves. There were drinks, parties and debauchery inside Number 10 Downing Street and government departments, while families were unable to see vulnerable relatives in care homes or attend funerals. Moreover, the prime minister was accused of misleading Parliament – one of the most serious offences in the British constitutional system. Would there be an appropriate political price and due process for holding him and others to account? Or would Britain be a country in which some former members of a political Bullingdon Club élite, could act without culpability?

In eventuality, Johnson did resign as prime minister after a wave of resignations from his own cabinet. And less than a year later, he was found to have misled parliament by a cross-party parliamentary committee and resigned from Parliament before any sanctions could come into effect. Parliamentary democracy delivered an accountability check on a leader who broke the rules.

But this outcome should not mask wider issues of democratic erosion and stress in the UK. A new report on developments in the quality of UK democracy evaluates the full democratic changes that the UK has witnessed since Johnson’s victory in 2019. It reveals that across a range of dimensions, British democracy has either been eroded and/or is in need of a charter for renewal.

A multi-dimensional democracy?

As one of the world’s oldest democracies, Britain has accumulated its own parliamentary quirks and terminology in terms of its democratic benchmarks. Within Parliament, terms such as “parliamentary sovereignty” and “ministerial codes” are much valued amongst members, alongside arcane practices and customs such as dragging speakers to the chair, and using the Serjeant at Arms to remove members of the public from spaces reserved for members. Genuine democracy requires more than parliamentary procedure, however, important as that is. Democracy is about power being dispersed across a country and being held in the hands of all citizens, rather than a narrow few at the top. Against a wider set of criteria, the time since Johnson was returned as prime minister with a majority has seen democracy being eroded.

Genuine democracy requires more than parliamentary procedure, important as that is.

Human rights, standards and the balance of powers across Parliament have seen troubling developments. There have been inquiries into the harassment and bullying of civil servants by senior ministers. There were claims of corruption, conflict of interest and bias concerning the awarding of government contracts during the COVID-19 period. The powers of citizens to protest have been undermined by new laws and “serious disruption prevention orders” which, in scenes more befitting the 17th century, saw Republican leaders arrested during the Coronation of King Charles III. The law has been unevenly delivered with Black citizens much more likely to be subject to police stop and search or fined for breaching COVID-19 rules. A report into the Metropolitan Police, commissioned by the Met after one of its own officers abducted Sarah Everard, “found institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia in the Met”. The government has attacked judicial constraints on its own power and shown brazen disregard to international law.

Democratic elections require that citizens have equal and free opportunities to participate in and contest elections. However, the government has introduced substantial changes to electoral law since 2019. Elections have seen the independence of the Electoral Commission now subject to a ministerial statement. Voter ID requirements put in place that prevented thousands of people from voting at the 2023 local elections. Meanwhile, media pluralism has been reduced to such an extent that three companies own 90 per cent of newspaper circulation and local journalism has been placed under severe pressures. The proposed Online Safety Bill will mean that unaccountable international online platforms, not courts, will be determining whether citizen’s speech is legal.

Merely holding elections to enable periodic and indirect involvement in political affairs by citizens is not thought to be sufficient for a full and vibrant democracy. Democracy should be fully participatory in order to embed citizens’ views and interests, with high voter turnout and wide opportunities for citizen’s to express their views. Party leadership elections have given their membership an ever-increasing opportunity to be involved in deciding their leaders. There have also been moves towards devolving power from Westminster through devolution deals which can strengthen the power of local citizens. However, referendums have been denied and the extent to which devolution policies have endowed local actors with real power has been questioned. Participation remains a major problem in Britain – with those not not voting at all in general elections (18.5 million) far outnumbering those that gave the government an outright majority in Parliament (14.0 million) in 2019.

Democratic societies work best when they foster genuine engagement and discussion about the political questions of the day and challenges facing them and use evidence and argumentation. References to scientific evidence in decision-making were heavily used to justify policy by the government during the pandemic period. However, there were also claims that the scientific advice was ignored, such as expert advice on providing COVID-19 tests for people going into England’s care homes. Moreover, opportunities for deliberation over legislation were reduced with the increase used of fast-tracked primary legislation and statutory instruments, which means that parliamentarians have less opportunity to discuss and consider proposed new laws.

For citizens to be able to participate and be active in a democracy, they need access to resources. However, such resources are often unevenly distributed and this pattern accelerated during the pandemic. Educational attainment inequalities increased during the pandemic and material living standards declined following record-breaking inflation rates. The political education that young people received in school was found to be inadequate. A democratic culture was further undermined by racism, misogyny, homophobia and transphobia across society and within key public institutions.

An agenda for change

Democracy matters for the UK at home and abroad. Britain’s position as a beacon for democracy is undermined on the world stage by democratic backsliding in its own yard. This has geopolitical consequences in an era of resurgence cold war divisions. But democracy matters because it brings transparency, trust and better decision-making at the top of government. After wasted public funds and failed decision-making during the pandemic, measures to strengthen democracy can improve public services, accountability and law and order. It is not expensive to implement democracy, but it is expensive not to.

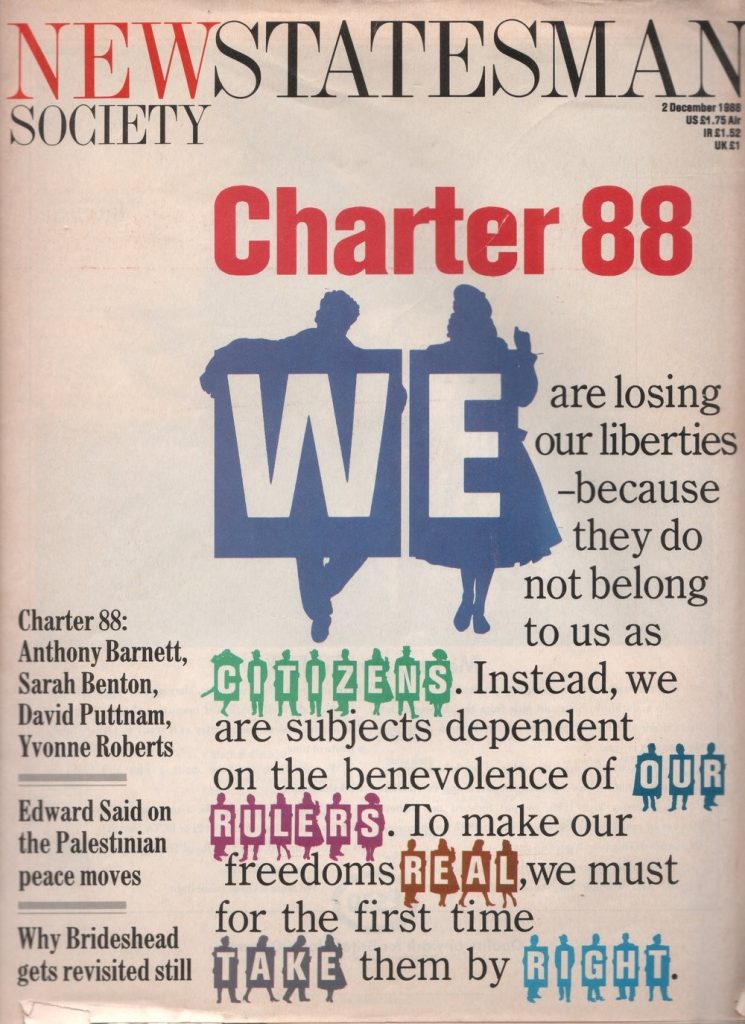

We are in a pivotal moment for democracy. There have been widespread concerns that we have entered a period of global democratic backsliding. According to the Varieties of Democracy Project, the level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen in 2022 is down to 1986 levels. In 1988, a Charter was signed to renew British democracy and this was influential in setting the policy agendas for the democratic reforms that followed. The demands of the Chartists, echoing the calls of those who called for a Magna Carta, were met with freedom of information, a bill of rights and House of Lords Reform introduced by the New Labour governments. Not all of the Charter 88 reforms were taken forward, however, and this failure meant that democracy was not fully safeguarded.

Now is the time for political parties, amid new threats, to make commitments towards renewing democracy and a new charter. This report provides a suggested pathway for such a charter which can be taken forward by all political parties in the next Parliament.

This post draws on the findings of the new report The UK’s Democracy Under Strain: Democratic Backsliding 2019-23. The report was funded by Unlock Democracy and builds from a working paper on realist democracy.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: UK Parliament, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)