The UK economy is currently experiencing unprecedentedly low levels of productivity, business investment and growth. Neil M Davies examines the link between this trend and the policy of defined benefit pension funds divesting significant sums from UK companies in recent years.

The UK currently suffers from abysmal productivity growth and chronically low investment compared to other countries. Economic productivity is among the most important indicators because it indicates how efficiently an economy produces goods and services. The UK’s abject economic productivity has resulted in stagnant wages, long hours, and plummeting living standards, which are falling behind other developed countries. This is the worst collapse in productivity seen in 250 years. Had productivity continued growing on its pre-2007 trends, labour output would have been 19 per cent higher in 2017. This gap is almost twice as bad as the next worst periods in the UK – the 1970s and 1890s, and four times worse than the 10 years following the great depression in 1929.

The UK’s abject economic productivity has resulted in stagnant wages, long hours, and plummeting living standards, which are falling behind other developed countries.

Why has UK productivity growth been so bad? Economists have debated many reasons: the financial crisis, the end of the information technology boom, Brexit… There is currently no consensus. However, one obvious explanation has yet to be widely considered: the forced divestment of UK Defined Benefit (DB) pension schemes from productive investment in the UK and international companies to unproductive investments in government bonds.

The UK’s Defined Benefit pension sector is unusually large – and had £1.7 trillion in assets in 2022. Before 2008, these schemes were major investors in UK companies. However, between 2008 and 2022, inept guidance and interventions from the Pensions Regulator (TPR) encouraged these schemes to divest from company shares and buy government bonds. This policy of DB schemes shifting their asset allocation from equities (ie, company shares) to bonds (ie, government and company debt) is often referred to as “derisking” or “liability-driven investment” (LDI).

A drastic reduction in investment

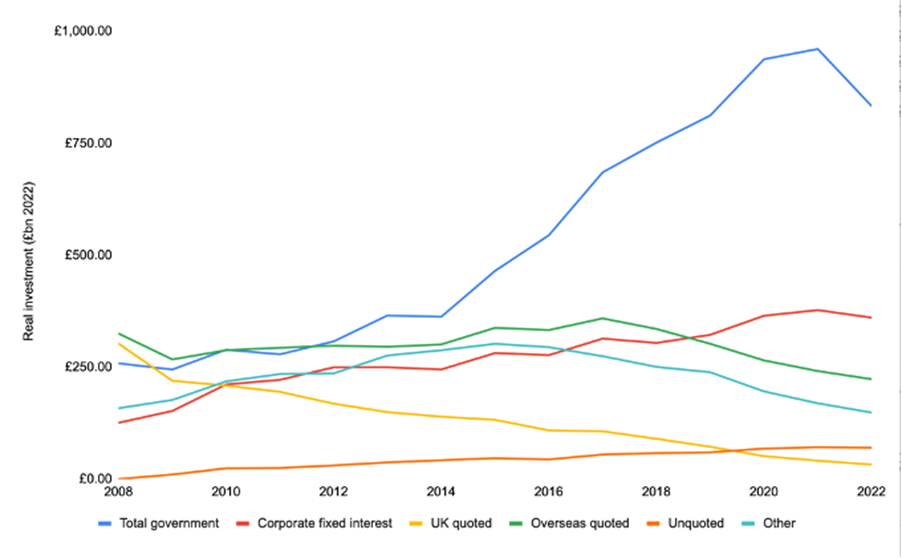

These policies have had an enormous impact on how these schemes invest. Figure 1 uses data from the Pension Protection Fund Purple Book, corrected for CPIH inflation (Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs). It shows a massive shift in asset allocation from equities to bonds. In 2008, schemes invested 67 per cent of their assets in equities and other investments (like property). 26 per cent of their assets were invested in UK company shares. By 2022, this had fallen to 28 per cent invested in equities and other assets and a mind-numbing 2 per cent in UK company shares. Schemes have radically increased their holdings in bonds, particularly government bonds. In 2008, schemes held around 33 per cent of their assets in bonds, of which 11 per cent were company bonds, and 22 per cent were government bonds. By 2022, they invested 72 per cent of their assets in bonds (50 per cent in government bonds and 22 per cent in company bonds).

Had UK Defined Benefit pensions schemes maintained their asset allocations from 2008, today they would invest £398 billion more in UK equities, £240 billion more in overseas equities, £460 billion less in government bonds, and £181 billion less in company bonds. Thus, over 14 years, TPR’s regulation of DB pension funds has reduced investment in UK and overseas companies by £28 billion and £17 billion annually. For context, the total outstanding government debt not held by the Bank of England was around £1,600 billion. TPR has, in effect, forced UK Defined Benefit pension funds to increase their holdings of UK government debt by over a quarter of all outstanding debt. This divestment will likely affect investment and, thus, productivity growth and living standards.

There has been a natural experiment in the UK DB pensions world – local authority schemes. These are not subject to regulation or “guidance” by the Pensions Regulator. They have not closed to new members and future accrual in the manner of private schemes. Their asset allocation to equities, of one form or another, is 65 per cent of their funds of £487 billion. This is extremely powerful evidence that the woes of private sector DB schemes, and the UK’s dismal rates of investment and productivity growth are due to TPR.

Wide-ranging impacts

What are the consequences of this? First, there are consequences for defined-benefit pension schemes and their members. Historically, the average return on UK bonds was low, just 2.3 per cent above inflation between 1870 and 2015. Worse, the market yield (interest rate) on index-linked gilts has recently been as low as -3.2 per cent below inflation. This reduction in the yield of UK government bonds has been largely driven by the demand from pension funds, as the Bank of England research showed. Interest rates this low imply these bonds will lose half their value over 30 years. This means pension funds will have, in effect, paying the government to borrow. In contrast, on average, UK equity investments returned 6.8 per cent per year above inflation 1870 and 2015.

Thus, reducing investment in equities by £648 billion will, on average, reduce UK DB schemes’ returns by £29 billion per year (or 1.45 per cent of UK GDP). These losses need to be paid by someone, either scheme members or the sponsoring employers. As a result, the costs of running these schemes have exploded, and most schemes have closed. This imposes major costs on employers who have had to pay as deficits have increased. Unsurprisingly, employers with large pension deficits and deficit recovery contributions tend to reduce their business investments, as found in Confederation of British Industry (CBI) surveys. Lower business investment will lead to lower productivity.

Second, and more perniciously, the divestment of UK-defined benefit pension schemes has been a fire sale of UK equities. As a result, the UK stock market has performed dismally over the last decade, underperforming most other markets. Did other forms of investment offset these changes? In 2019, UK stocks and shares individual savings accounts (ISAs) had only £38 billion invested in shares, only a portion of which will be UK equity. In 2022, occupational-defined contribution schemes only had £111 billion in assets, again, only a fraction of which will be invested in UK equities. These sources of capital can’t offset the overall reduction by UK DB schemes.

Finally, there is foreign investment. Foreign investors have increased their investments, partly because UK equities markets have been extremely cheap. However, total annual net foreign direct investment flows to the UK were only £55 billion, and there’s no evidence, or even analysis, which suggests that net foreign direct investment (FDI) flows have increased because of UK-defined benefit pension funds divestment.

What is to be done?

Inept guidance from TPR has imposed enormous costs on UK pension funds, UK companies, and UK pension scheme members. The private costs to members are clear, the loss of valuable future accrual of pensions. The loss to the broader economy from the UK’s ongoing economic stagnation is harder to calculate and is less well known. TPR’s regulation is in effect, a form of financial repression where investors are forced to lend to the government at a real loss.

1. Reform TPR

The Pensions Regulator must be reformed to protect pension scheme members and the UK economy. It appears to have been captured by the industry it is supposed to regulate and has acted in the interests of a small group of actuarial and investment advisors. Actuarial firms have substantially profited from advising pension funds to divest, derisk and transfer their pension liabilities to insurers. It is clear that TPR has not acted in the interests of scheme members and is not fit for purpose. It urgently needs to be replaced by a regulator focused on the interests of scheme members and the broader UK economy rather than a narrow clique of investment advisors.

2. Encourage DB schemes to invest productively

Defined Benefit schemes hold a large fraction of UK capital. The UK productivity crisis will not be resolved until investment in and by companies increases. Therefore, we urgently need to reform regulations to encourage DB schemes to invest productively rather than forcing them to waste their members’ capital by lending it to the UK government at a real loss.

The UK is experiencing a historically unprecedented collapse in productivity, business investment and growth. A plausible explanation is that over the last 15 years, UK DB pension funds have divested around £400 billion from UK companies. This divestment explains the simultaneous collapse in UK business investment, productivity, economic growth and living standards. If future governments aspire to improve UK investment, productivity and living standards, TPR’s financial repression of UK DB pension schemes must end.

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.” (Keynes, 1936)

With apologies to Modigliani and Miller.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Tim Mossholder via Unsplash