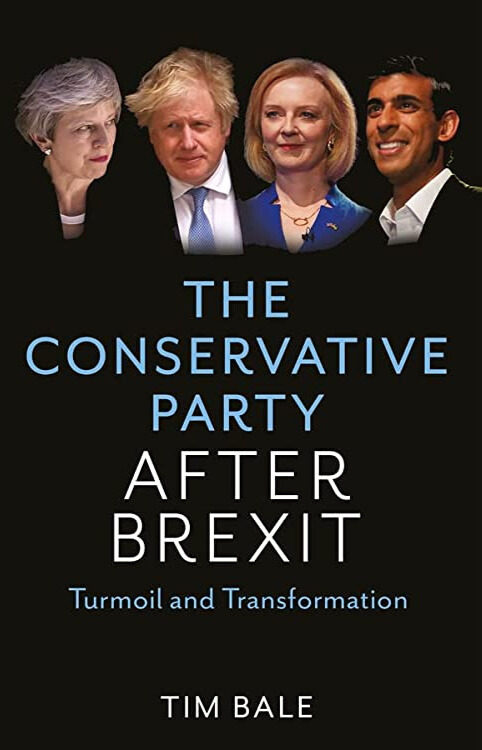

In The Conservative Party After Brexit: Turmoil and Transformation, Tim Bale dissects the complex dynamics of a divided party attempting to use the Brexit referendum result to political advantage. Tracing the shifts in leadership and agenda over the past several years, Bale offers up a skilful anatomy of a tumultuous period in the history of the Conservative Party, writes James Dennison.

The Conservative Party After Brexit: Turmoil and Transformation. Tim Bale. Polity. 2023.

Tim Bale’s skilful study of “The Conservative Party After Brexit” shows a party desperate to instrumentalise a constitutional upheaval that most of its MPs had opposed, leading to its own, and the United Kingdom’s, “Turmoil and Transformation”. The book does several things well. Bale broadly conceptualises the party by including: the “party in the media,” as the author terms those newspapers with a symbiotic relationship with the party; the myriad new caucuses seeking to ape the impact and visibility of the European Research Group (on China, the North, Covid Recovery, “Common Sense”, Net Zero, etc.); and the party membership who, as the all-important “selectorate”, provide ongoing fuel to internal manoeuvrings via regular cabinet approval ratings and on whom the author is an expert. Bale uses a deft balance of sources – qualitative and quantitative, academic and non-academic, on the record and very much off it – to support his lucid account of the seven-year history of the party.

Tim Bale’s skilful study of “The Conservative Party After Brexit” shows a party desperate to instrumentalise a constitutional upheaval that most of its MPs had opposed, leading to its own, and the United Kingdom’s, “Turmoil and Transformation”. The book does several things well. Bale broadly conceptualises the party by including: the “party in the media,” as the author terms those newspapers with a symbiotic relationship with the party; the myriad new caucuses seeking to ape the impact and visibility of the European Research Group (on China, the North, Covid Recovery, “Common Sense”, Net Zero, etc.); and the party membership who, as the all-important “selectorate”, provide ongoing fuel to internal manoeuvrings via regular cabinet approval ratings and on whom the author is an expert. Bale uses a deft balance of sources – qualitative and quantitative, academic and non-academic, on the record and very much off it – to support his lucid account of the seven-year history of the party.

Conservative MPs were quick to promote themselves as the answer to whatever the vote “really” meant.

Above all, the author shows that, since 2016, the Conservative Party have been concerned with, first, projecting interpretations onto a policy that most of its MPs had opposed and, second, actively seeking to use that policy for electoral gain. In doing the former, the Tories were hardly alone: commentators and academics have equally promoted some sensational and motivated explanations for the 2016 vote. However, combined with the pursuit of electoral victory, the result has been what Bale shows to be a mixture of absurdity and poor governance. Conservative MPs were quick to promote themselves as the answer to whatever the vote “really” meant – from opposition to elites, experts, business, and institutions to a “cry of pain” from the (disproportionately homeowning) oppressed. They did so primarily through rhetoric, but also various grandiose political visions tenuously tied to Brexit that rarely came to much at all. Indeed, the cardinal sin throughout the book – as committed by Theresa May and Nick Timothy (38, 41) – is to take Brexit seriously as an intellectual project beyond simply leaving the EU and winning elections. Those Remainers who more soberly saw Brexit as “damage limitation”, such as Philip Hammond (66, 71), were eventually side-lined as a drag on the motivation needed to get Brexit across the line. Bale does a fantastic job of exhibiting May’s dawning realisation of the magnitude of leaving the EU and her own limitations, as – increasingly curtailed and conflicted – her overcompensating “new iron lady” aesthetic and communitarian grand projet were reduced to a series of grinding “meaningful vote” defeats. By contrast, the ERG – bona fide Leavers for whom Brexit simply meant leaving the EU as much and as soon as possible – were on far firmer psychological terrain. Bale shows that the EU also soon realised the best way to protect itself was to calmly let the Conservative Party tie themselves in knots while the clock ran down.

The cardinal sin throughout the book – as committed by Theresa May and Nick Timothy (38, 41) – is to take Brexit seriously as an intellectual project beyond simply leaving the EU and winning elections.

In this context, a certain insincerity was a virtue and one that Bale demonstrates that Johnson held in abundance (“Opportunism knocks”, 94). This allowed him to align the various components of the Conservative Party as broadly conceptualised by the author. Even taking COVID-19 into account, the sheer lack of policymaking during the Johnson years stands out. “Levelling-up” is repeatedly delayed before manifesting as a patchwork of underwhelming rebrands and pork-barrel politics, seemingly having done its job as an electoral support act for getting Brexit “done”. Bale makes great use of humour throughout: MPs’ estimations of their own abilities and support from peers are repeatedly disappointed; Johnson’s stint in No. 10 is particularly absurd (asking Chris Whitty to inject himself with COVID-19 live on air to “prove” its mildness, anyone?); and well-timed tabloid “screamers” from the “party in the media” round off his analyses (“RISHI: HANDS OFF MY MISSU”’). He also uses the occasional echo of the Cameron years to contrast just how distant and insignificant that period already was for internal party politics (186).

Even taking COVID-19 into account, the sheer lack of policymaking during the Johnson years stands out.

The final chapter paints a picture of the party reaching the bottom of the Brexit barrel (now refashioned as a libertarian project) under Liz Truss before the markets call time and the party is forced to move on under Sunak. After six years and 277 pages of Conservative machinations and Brexit boosterism, Truss railing against “vested interests dressed up as think tanks, talking heads, and Brexit deniers” felt like pure projection. That a whopping three-quarters of her short-lived cabinet went to fee-paying schools (287) makes one wonder how Bale’s concept of “party in the media” could be extended to a broader network, including donors and establishment institutions. Though Bale notes the unimportance of the lack of ERG “spartan” support in Sunak’s eventual selection and, once Prime Minister, his singular focus on competence to woo the electorate, he interprets this less as evidence of further fundamental transformation and more of a sobered-up party desperate to fix the electoral mess it is in, with voters’ eyes now firmly on Britain’s poor economic performance. Brexit’s legacies in the party, according to Bale, are more trifling: “emotional and ideological sunk costs; amongst a cohort of MPs for whom ‘sticking it to the leadership for the sake of it’ has become a pleasurable pastime and a great way to get on TV” (298).

It is a British political cliché to say that the Tories usually find a way to win, a possibility Bale does not discount in 2024. However, it is hard to see how after the party has so thoroughly transformed itself around Brexit, for now both ‘done’ and unpopular. Had the party chosen a more prosaic interpretation of the referendum – a vote of no confidence by a historically Eurosceptic public against a crisis-beleaguered EU – the subsequent policy prescription, economic and diplomatic damage limitation, would have left Britain in a stronger position. Instead, as Bale shows, the political imperatives within the Conservative Party and opportunities outside it convinced its leaders either to interpret the vote as representing something more so that leaving the EU should either be one part of a broader, equally inchoate reshaping of Britain (as demonstrated by May) or to instrumentalise it for what could only ever be short-term electoral gain (as demonstrated by Johnson). Both required all manner of hyperbole, denial, and damage. All that said, the seismic 2016 vote to leave was respected and acted upon with a deal and within highly demanding parameters—more than a lot of democracies might have done. But “burning injustices” were not remedied, regions weren’t “levelled up”, and Britannia wasn’t so much “unchained” as unmoored. Sunak’s achievements and promises are at least partially exercises in belated Brexit damage limitation. As Bale’s excellent ‘The Conservative Party after Brexit’ makes clear, there is good reason why ‘psychodrama’ has become another British political cliché, making his book a lot more enjoyable to read than the events it dissects were to live through.

This blogpost originally appeared on LSE Review of Books. All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Number 10, Creative Commons — Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic — CC BY-NC-ND 2.0