Harry Pickard, Vincenzo Bove, and Georgios Efthyvoulou present evidence that individuals were less inclined to move in the aftermath of the EU referendum when they were aligned with the Brexit preferences of their district. As Remainers found themselves on the losing side, they were more likely than Leavers to value the alignment to their district, given their ‘misalignment’ to the country.

Major polity-shaping events, like the UK’s 2016 decision to leave the EU, can have important consequences on people’s attitudes and behaviour. The Brexit vote has deepened existing divisions in the British society over key issues, such as national identity, globalisation, and multiculturalism, and generated salient ‘affective polarisation’, with individuals segregating themselves socially and distrusting people from the opposing side. Perhaps not surprisingly, the referendum has also affected people’s life satisfaction and mental distress, and led to fallouts with family and friends.

In a recently published study in Political Geography, we investigate whether such hostile culture of ‘othering’ political rivals can affect broader social relationships by changing individuals’ propensity to migrate internally. Existing research has largely focused on the geographic sorting of the American electorate, and little attention has been given to other countries. And while one of our recent works shows that internal migration choices are strongly affected by political preferences also in the UK – and districts with the same political preferences exhibit higher migration flows – there is no evidence of the effect of Brexit as such. The unique circumstances of Brexit, with a near 50-50 vote and the fractious discussions around its future, make the EU referendum a particularly suitable test-bed to examine the consequences of polarising politics on internal population movements.

But how exactly did the Brexit referendum affect internal migration choices? There are two complementary behavioural explanations for our research question. First, we could expect the referendum outcome to make people more polarised. In fact, the national split revealed and reinforced by the Brexit vote has popularised the notion of a ‘divided Britain’, an expression frequently used to capture a growing sense of social and political polarisation. As Brexit identities have reinforced themselves in the aftermath of the referendum, often surpassing traditional party identities, political differences became more salient, in turn affecting internal migration decisions. Second, the referendum returns could have made latent divisions that already existed in the population more visible and consequential or provided new information about the aggregate political preferences of the district of residence. This could be particularly important considering the high degree of uncertainty around the Brexit outcome and the forecasting errors of financial markets and opinion polls, which did not anticipate the victory of “Leave”.

We leverage comprehensive survey-based data for around 18,000 individuals from the UK Household Longitudinal Study, and examine whether the change in relocation patterns from before to after the referendum date of 23 June 2016 was different for different groups of people, depending on their ‘political alignment’ status – with the latter defined as having the same preferences over EU membership as the majority (at least 50%) of people residing in the same district. Our estimation strategy is designed to address ‘self-selectivity concerns’; that is, unobserved factors affecting both relocation decisions and people’s preferences towards Brexit.

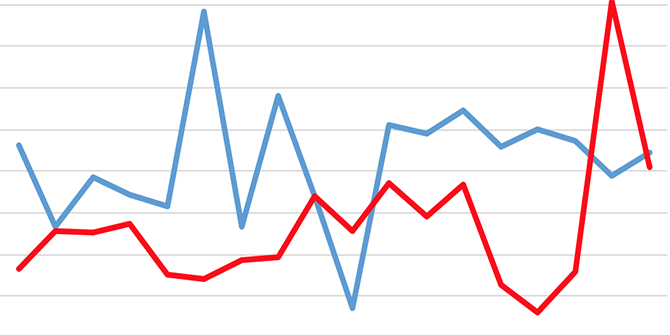

Our analysis reveals that individuals’ migration choices are indeed influenced by deviations from community preferences. We find that UK citizens were significantly less likely to move to another district after the referendum when they were strongly aligned to their district of residence. At the same time, we find that this ‘alignment-induced’ effect is mostly driven by Remain supporters. On the one hand, as Remainers found themselves on the losing side, they were more likely to value the alignment to their district, given their ‘misalignment’ to the country as a whole. As those who preferred to remain in the EU became also worse off in terms of mental health, they were less inclined to leave neighbours who share similar political values. On the other hand, as Leavers won nationally, local alignment matters relatively less for them, and only when their district’s share of Leave votes is particularly high.

Our analysis also provides evidence that the main channel underpinning our results is the desire for ‘political homophily’; i.e., living in areas with political views similar to your own can satisfy your need for belonging and thus reduce the likelihood to relocate. Using information on the destination districts, we show that, after the referendum, non-aligned individuals were more likely to move to a district to which they could then feel aligned.

If the referendum served initially to polarise attitudes towards the EU, the subsequent Brexit process has served to ensure that the legacy of the referendum is still present despite the fact polling day has long since come and gone. In fact, scholars and political commentators have increasingly warned about the increasing ‘tribalisation’ of British politics. Existing divisions do not only mirror divergences over the consequences of Brexit as such, but also in terms of people’s sense of identity and the values they uphold, given the implications of EU membership for cross-border migration and issues of sovereignty.

By reinforcing the presence of politically homogeneous communities, deepening political divides do not only discourage the discussion of opposing viewpoints; they can also promote intolerance which can ultimately damage the social fabric of a country. Ultimately, in the long run, higher local homogeneity in citizens’ political preferences could further exacerbate divisions across the British society.

_______________________

Harry Pickard is Lecturer in Economics at Newcastle University.

Vincenzo Bove is Professor of Political Science in the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Warwick.

Georgios Efthyvoulou is Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Sheffield.

Photo by Kelli McClintock on Unsplash.