False beliefs about migration run the risk of worsening existing divisions in public debate. While efforts to insert facts into these debates can make perceptions more accurate, can they also alter what people think and want? In new research, William Allen, Kristoffer Ahlstrom-Vij, Heather Rolfe and Johnny Runge find that communicating economic evidence about EU immigrants – including through common visual means like charts and animated video – has the potential to shift attitudes on the issue.

When it comes to sensitive political issues like migration, people often encounter incorrect information – either through their everyday conversations, in the media, or in statements made by politicians. Whether this arises from honest mistakes or efforts to intentionally mislead, it has generated concerns among many people about whether what they think about migration is based on good evidence, something that has partly motivated resurgent interest in fact-checking.

After all, as people form their opinions and preferences towards migration, their understanding of key facts likely feeds into that process: how many migrants are in a country; what kinds of work do they do; what impact do they have on the economy? On these questions, surveys regularly find that people are largely uninformed: for example, people usually overestimate the proportion of foreign-born people in their own countries.

Studies have shown how fact-checking can reduce ignorance but it is less clear whether providing information on a polarising topic like migration can move attitudes in any particular direction.

This matters because people might have expressed different beliefs and preferences if they had factually correct information about the issues at hand, as several studies have found. But while studies around the world have shown how fact-checking can reduce ignorance, it is less clear whether providing and acquiring that information on a polarising topic like migration can move attitudes and preferences in any particular direction, if at all. Moreover, despite the popularity of communicating information in visual ways (such as through charts and infographic videos) and the possibility that people might learn differently through visuals than text, there isn’t much evidence of how the effectiveness of these techniques compares to conventional text-based messages.

Messaging modes and migration attitudes: Looking at the evidence

In our research, we addressed both problems in the context of UK attitudes towards immigrants from the European Union, since EU migration was central in determining how people voted in the 2016 referendum on EU membership. We developed short messages (called experimental “treatments”) conveying the modestly positive impacts of EU migrants on the UK economy. While the main claims were identical and based on publicly-available data, we presented them in different forms: one message was only text, the second had accompanying charts, and the third was an infographic video in which a narrator read the same text.

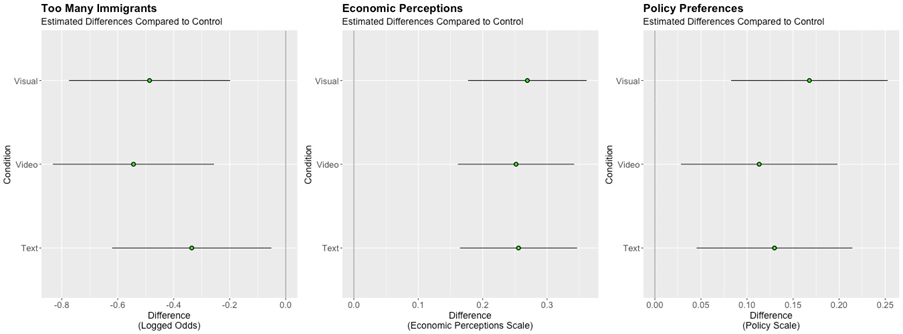

We found that all three forms of messaging moved attitudes and preferences towards more favourable views of migrants (see Figure 1). Specifically, compared to people who didn’t see any message (the “control” group), people who saw the messages were less likely to think the UK had allowed too many immigrants to enter the country and more likely to view EU immigrants as having positive economic impacts. They were also more likely to support less restrictive immigration policies. However, the messages were not more effective for being communicated with charts or as an animated video, compared to text alone.

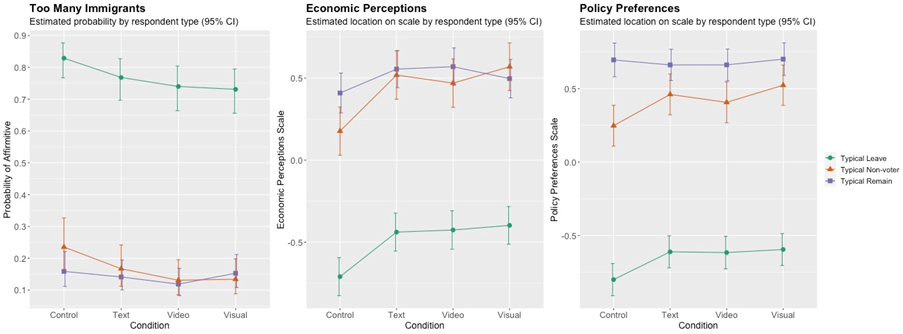

Moreover, while we thought the messages might be less effective or even backfire among those already having more negative views about immigrants, we actually found that the positive effects were particularly strong among people who either voted Leave or did not vote at all (see Figure 2). These are groups which our study showed to hold sceptical and mixed views on migration, respectively, and who also account for a considerable proportion of citizens as demonstrated by research from British Future. (It is also possible that Remain voters were less affected by the messages because they already held positive views – a kind of “ceiling effect”).

Further research into how information shapes immigration attitudes is needed

These results are consistent with the idea that people on both sides of an issue update their views when they encounter new information. Therefore, we think efforts to insert evidence into important policy debates – as immigration and its impacts continue to be for the UK – warrant further investigation for two reasons. First, voters’ choices may be sensitive to what they know about migration in the shorter-term. Second, there are broader and more long-term concerns about what the quality of public debate signals for how well democracies are working.

Communicating factual information about these issues is an important lever available to journalists and policy-makers.

At the same time, it is important not to downplay evidence that attitudes to immigration may display a degree of longer-term stability in the face of crises and communications-based interventions such as the ones we tested. Moreover, choices about what migration policies to pursue or which migrants to prioritise often involve trade-offs that do not always have clear or objective standards that can be fact-checked. For instance, should migrants who worked in frontline health services during the pandemic be given long-term residency?

While recent surveys suggest that British attitudes towards immigration have become somewhat more positive, particularly towards migrants working in jobs described as “essential” or “key” during the COVID-19 pandemic, we think this actually highlights the possibility of public opinion on immigration moving as people learn more about contextual factors such as labour markets and crisis responses—and the roles that immigrants play in these.

Communicating factual information about these issues is an important lever available to journalists and policy-makers. Understanding whether and for whom these approaches are effective should be a priority for researchers.

This blog is based on the authors’ paper “Communicating Economic Evidence About Immigration Changes Attitudes and Policy Preferences” which is published open-access in International Migration Review.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: UK Border, Terminal 4, London Heathrow by David McKelvey, License: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)