The vision of post-Brexit Britain was one of international trade deals that would propel the country into a new era of prosperity. That vision of “Global Britain” is now dead. Thomas Sampson argues that the only viable alternative is a closer trade relationship with the EU.

Brexit marked a fresh start for UK trade. After nearly fifty years under the EU’s common policy, Britain was free to set its own tariffs and strike its own trade deals. Theresa May declared that the era of “Global Britain” – a country committed to free trade and determined to broaden its horizons away from Europe towards faster growing economies in Asia and the Americas – had begun. Newly recruited trade negotiators criss-crossed the globe seeking ambitious deals with the United States, India and any other country willing to talk.

It is time to concede that this vision of “Global Britain” has failed. Brexit has not turned the country into a global trading superpower. The much hoped-for deal with the US, the UK’s second biggest trade partner after the EU, has failed to materialize. Negotiations with India are ongoing, but any agreement that does emerge will be limited in scope and bring only minor changes. New deals have been struck with Australia and New Zealand, and the UK has joined the CPTPP – a free trade agreement between 11 Pacific Rim countries. But these economies are too small and too far-away to matter much for UK trade. Even the government’s own analysis suggests that the economic benefits of these deals will be minor, with each agreement expected to increase UK GDP by less than one-tenth of one per cent.

Far from boosting trade, Brexit has left the UK less open to the world. Growth in goods exports and imports since 2019 has been the weakest in the G7.

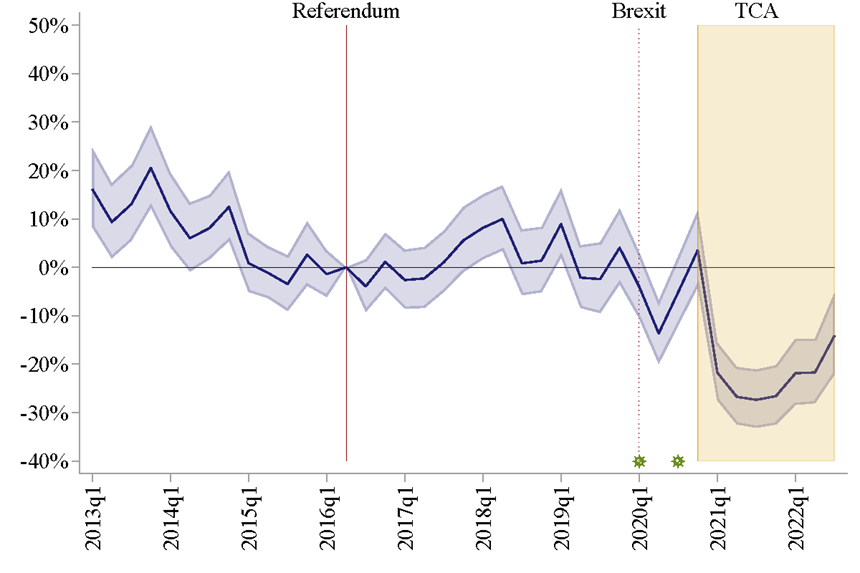

Meanwhile, under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) that now governs UK-EU trade, Britain sits outside of the EU’s Single Market and Customs Union. This change has resulted in the re-introduction of customs red tape and regulatory barriers, leading to higher trade costs. And although services trade has proved surprisingly resilient so far, these costs have sharply reduced goods trade. The TCA has caused goods imports from the EU to fall by around twenty per cent relative to the change in imports from the rest of the world, as shown in Figure 1. Likewise, many small exporters, who cannot afford to hire new staff simply to complete customs forms, have seen their exports to the EU collapse.

Figure 1: TCA and Goods Imports from EU relative to Rest of the World

Far from boosting trade, Brexit has left the UK less open to the world. Growth in goods exports and imports since 2019 has been the weakest in the G7. And less trade has contributed to the ongoing stagnation of the UK economy. On the import side, trade barriers increase the cost of buying goods and services from the EU, leading to higher consumer prices. While on the export side, trade barriers reduce opportunities for UK firms, leading to fewer good jobs and lower wages.

Given all this, what should be the future of UK trade policy? The first step is to ditch the myth of Global Britain. The EU is far and away the UK’s most important trade partner, accounting for around half of all UK trade. At a time when advocates for globalization are on the defensive, there is little opportunity to strike transformational trade deals outside Europe. Instead, attention needs to shift closer to home. A stronger trade relationship with the EU should be the number one priority. That does not mean ignoring the rest of the world; the UK should be alive to opportunities wherever they emerge. But from now on officials should be taking more trains to Brussels and fewer planes to Tokyo, Canberra and other far-flung locales.

Unless the UK rejoins the EU’s Single Market, there will always be regulatory barriers to UK-EU trade. And unless the UK rejoins the Customs Union, cross-channel trade will always be subject to customs red tape.

It would be comforting to think that a renewed willingness to engage with the EU will lead to the dismantling of trade barriers created by the TCA. Comforting, but wrong. Unless the UK rejoins the EU’s Single Market, there will always be regulatory barriers to UK-EU trade. And unless the UK rejoins the Customs Union, cross-channel trade will always be subject to customs red tape. If the goal is simply to boost the economy – by around four per cent of GDP according to the OBR – rejoining the Single Market and Customs Union would be the best option. But absent a political consensus to take this step, a judicious combination of negotiations and unilateral actions could still mitigate some of the costs of Brexit.

Building upon the recent agreement to rejoin the EU’s research funding programme Horizon Europe, objectives for negotiations with the EU should include: i) an agreement on animal and plant health standards to ease the flow of agricultural goods across the channel; ii) improvements to labour mobility to facilitate short-term business trips and give young people opportunities to live and work in Europe, and; iii) rejoining ERASMUS to allow students to study in the EU. These steps would deliver tangible benefits to some of the groups hardest hit by Brexit. Helpfully, the UK Trade and Business Commission has compiled many more suggestions for improving UK trade policy. A key priority should be to support small and medium-size firms in exporting to the EU under the TCA.

But the most important short-term goal should be to avoid creating further barriers to trade through counter-productive regulatory divergence. And this goal can be achieved without the need for negotiations. Any proposed change to UK regulation should be subject to a cost-benefit test that accounts for how differences between UK and EU regulations affect trade. This test would prevent active divergence that is not in the UK’s interest. At the same time, the UK needs to tackle the passive divergence that occurs when EU regulations change. New or updated EU regulations should trigger a review of whether the UK would benefit from mirroring EU policy.

Shadowing the EU in this way – for example, by linking the UK’s carbon price to the EU regime to ensure that UK exporters are exempt from the EU’s carbon border tax – may be less glamorous than rhapsodising Global Britain. But the time for grand visions has passed. Now is the time to focus on the nitty-gritty of rebuilding UK trade.

This article is an edited version of an article originally published as part of the UK In A Changing Europe report “The State of the UK Economy 2024”.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Claire Louise Jackson on Shutterstock