The UK has had considerable success in improving gross hourly wages at the bottom of the distribution. However, Thomas Stephens shows that the sufficiency of workers’ overall net earnings – accounting for hours worked, and pay deductions – hasn’t improved in the same way as hourly wages over this same period. He argues for a focus on Earnings Sufficiency, and its key drivers, to improve UK job quality.

For understandable reasons, trends in gross hourly wages play a huge role in debate about the state of the UK economy. Most discussions of inflation focus on wages, with headlines like “wages are finally keeping pace with inflation” and “record UK wage growth fuels inflation concerns” abounding in recent weeks.

In the same vein, by far the most impactful public policy interventions in UK job quality have been in the area of wages.[1] As the Economy 2030 inquiry has highlighted, over the past two decades the Minimum Wage and (latterly) National Living Wage have almost halved the share of low-paid workers in Britain.

However, this debate isn’t capturing everything about the experience of low-quality work in Britain today. We also need to consider the sufficiency of peoples’ overall earnings, alongside crucial non-pecuniary aspects of work such as hours worked and the availability of flexible work arrangements.

The dual role of earnings in job quality

“Job quality” is a notoriously slippery concept, but there is some agreement in international literature that it encompasses two distinct aspects of earnings. The OECD Job Quality Framework measures both average earnings and the worker’s position in the earnings distribution, whilst the European Job Quality Index uses an indicator of “spending power from wages” alongside one for “the share of the working poor in the employed population.”

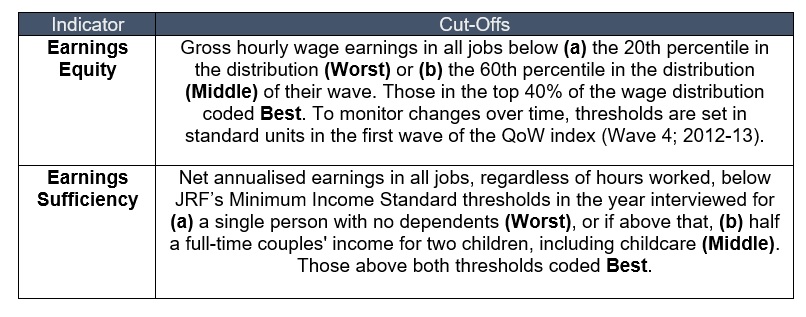

In a new UK Quality of Work (QoW) index, using data from a large-scale UK household survey (Understanding Society), I capture these twin concepts using two indicators of earnings:

- Earnings Equity. When we talk about good work, we care about our own position in the earnings distribution, not least because this is a signal of the intrinsic worth society attaches to our job. I suggest this is best measured by where a worker’s gross hourly wages sit within this distribution.

- Earnings Sufficiency. Yet distinct from the above, we also care about getting enough resources from work to meet (and ideally far exceed) some societally-agreed minimum. For this, I measure whether net earnings are enough to meet the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s (JRF) Minimum Income Standards (MIS). These are updated every year following a process of public engagement about the things people with different life and family commitments would need to achieve what the JRF terms a “socially acceptable standard of living.”

The QoW index uses a cut-off approach to assign every paid worker scores on these indicators. There are three possible scores in each indicator (Worst, Middle, and Best), depending on whether the worker meets or exceeds the relevant cut-off for each indicator (see Table 1).

Many commentators confuse gross hourly wages and net earnings. Even the aforementioned articles on inflation sometimes refer to “wages” when actually citing ONS measures of “total pay.” Yet while the measures are related, there is no reason to assume an improvement in Earnings Equity would lead to a corresponding improvement in Earnings Sufficiency. And both are important to job quality, for distinct reasons.

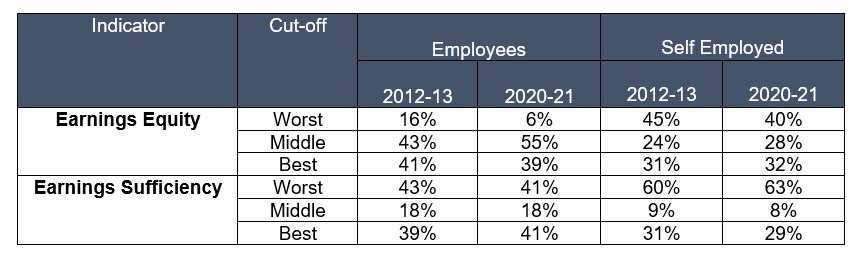

Table 1. Indicators and cut-offs for the Earnings dimension of the UK QoW Index.

Divergent trends in Earnings Sufficiency vs. Earnings Equity

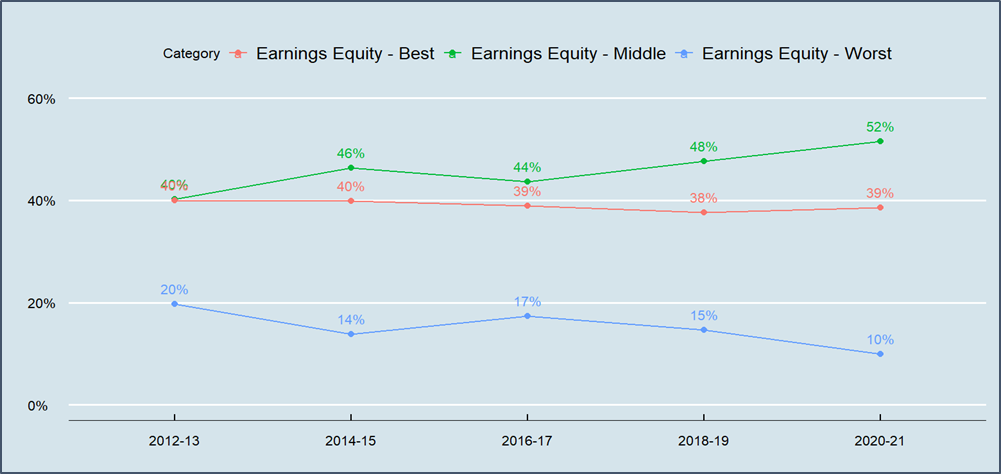

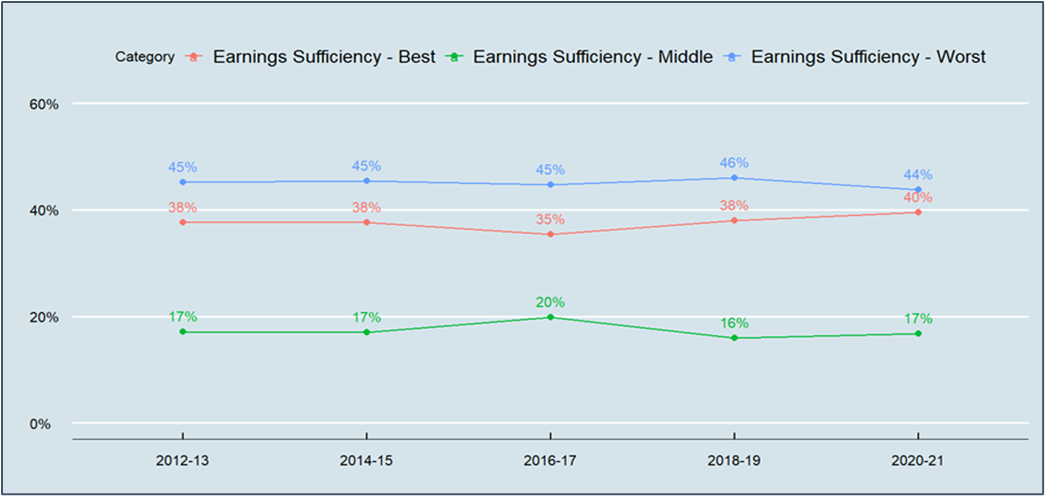

The data suggests that, indeed, trends in Earnings Equity and Earnings Sufficiency have not been the same. Consistent with other studies, the UK QoW Index shows a considerable improvement in hourly wages at the bottom 20 per cent of the distribution over the past decade (Figure 1). But this hasn’t translated into an improvement in Earnings Sufficiency, where no clear trend is apparent (Figure 2).

When we delve within the UK workforce (Table 2), the data show employees have disproportionately benefitted from the improvement in Earnings Equity. They may have even seen a potential slight improvement in Earnings Sufficiency, but a slight decline for self-employed workers. This provides further evidence of growing polarisation in the job quality of employees in comparison to self-employed workers.

Figure 1. Weighted proportion of UK workers scoring Worst (below 20th percentile earnings distribution), Middle (20th-60th percentile) and Best (top 40%) in Earnings Equity, 2012-13 to 2020-21.

Figure 2. Weighted proportion of UK workers scoring Worst (below Minimum Income Standard for single person), Middle (below 50% of MIS for 2-child couple, with childcare) and Best (above both thresholds) in Earnings Sufficiency, 2012-13 to 2020-21.

Table 2. Weighted proportion of employees vs. self-employed workers scoring Best, Middle and Worst in Earnings Sufficiency and Earnings Equity – 2012-13 vs. 2020-21.

Delving into the drivers of these trends

There are several logical reasons why an improvement in wages would not lead to a corresponding increase in Earnings Sufficiency:

- Hours worked could fall, or the distribution of hours among workers might change (conversely, for salaried workers, excessive working hours might not be translated into an improvement in earnings);

- Pay deductions increase, reducing net but not gross pay;

- Societally-agreed minimum standards, and/or the price inflation of any minimum standard basket of goods, increase faster than wages.

These are far from trivial possibilities. Even when a worker is legally entitled to higher minimum wages, employers could respond to this by taking a more restrictive assessment of the hours taken to do a given job – a particular risk for self-employed workers. Pension enrolment might improve at the expense of pay deductions, which might not be captured even in many net earnings variables. Or high wage growth can be netted out by even higher inflation.

Within the QoW index, self-employed workers have indeed seen a significant fall in average working hours over the course of the past decade – mostly driven by the entrance of newly self-employed workers, often under-employed and with fewer other employment prospects, into the QoW index. It remains to be seen how the post-pandemic fall in self-employment will affect this picture.

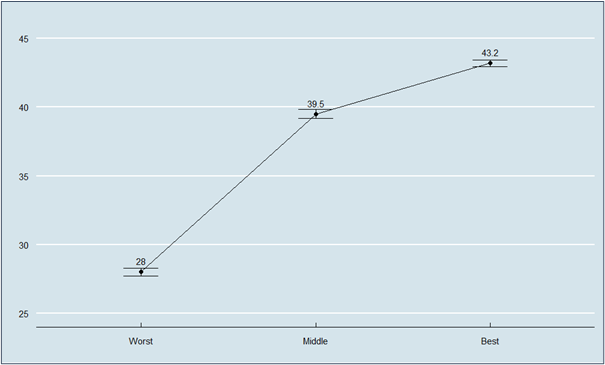

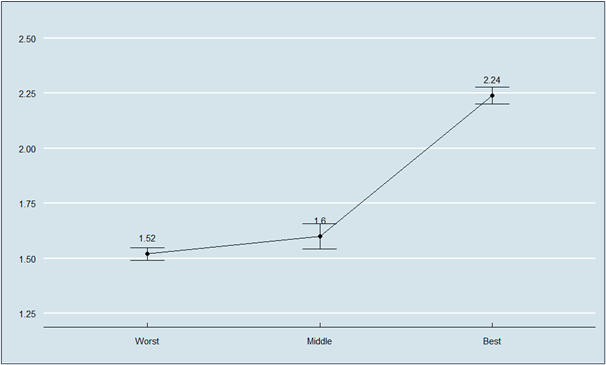

The data also shows that those with insufficient earnings access jobs which have significantly lower hours, but also significantly fewer flexible working opportunities (Figures 3-4). This suggests that many of the most disadvantaged workers in the labour force struggle to find flexible work opportunities, and instead tend to disproportionately reconcile life and family commitments by working fewer hours – thus affecting the sufficiency of their earnings.

Figure 3. Mean weekly working hours, including overtime, self-employed and additional jobs, by Earnings Sufficiency score, 2020-21. Standard errors in error bars.

Figure 4. Mean number of flexible work arrangements – such as working from home on a regular basis, part-time working or job sharing – available to employees in workplace by Earnings Sufficiency score, 2020-21. Note: this data is for employees only. Standard errors in error bars.

Resolving the blind spots in the job quality debate

The UK’s drive to improve minimum wages has made us an international exemplar in tackling low-paid work, drastically improving the position of the most disadvantaged in the earnings distribution. Future governments can, and should, continue with these improvements.

Yet despite this, we continue to struggle to tackle other important issues with job quality – with many workers stuck working lower hours, and in more insecure and precarious jobs, than they would like. They are thus unable to make a living from work despite the improvement in gross hourly wages. This perhaps partly accounts for why 38 per cent of people on Universal Credit in England are in employment, and why the number of households receiving Universal Credit payments hasn’t returned to pre-pandemic levels.

How to address this? We need to start by shifting our focus on improving job quality more broadly and tackling the deeper drivers of low-quality work which force the most disadvantaged workers into inflexible jobs with insufficient earnings. A good start might be to make flexible working opportunities the norm rather than the exception. The most advantaged workers have the privilege of being able to work more flexibly without this affecting their earnings sufficiency; so should everyone else.

[1] As a caveat, this is rivalled only by improvements in employee pension coverage following the introduction of automatic enrolment in the Pensions Act 2008, which has led to a considerable increase in the proportion of employees enrolled on workplace pensions over the past decade. The self-employed have seen no such improvement in personal pension enrolment over the same period. Which of these two are the most important interventions depends very much on the relative weight you assign to wages vs. pensions in job quality.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Louis Hansel via Unsplash.