The process of allocating levelling up funding has drawn criticism for a number of reasons. However, the controversy surrounding the latest round is merely another chapter in the story of regional policy suffering the impact of ideological and political battles, explain Patrick Diamond, Jack Newman, David Richards and Andy Westwood.

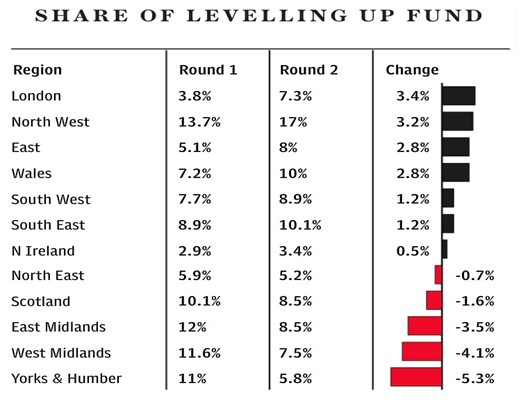

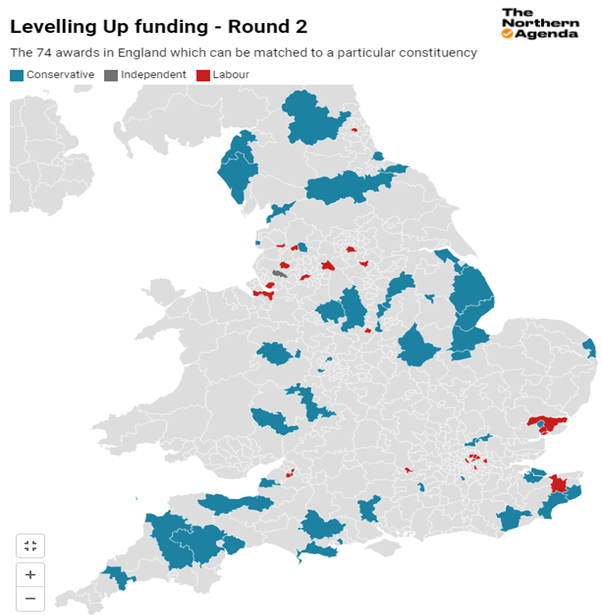

The recent outcome of the second of three rounds of the government’s levelling up fund has drawn a myriad of reactions. The process involved 529 bids submitted, and with only 111 funded projects, it is unsurprising that some responses have focused on the success or failure of individual bids, but this tells only part of the story. The government’s overall approach to levelling up has generated significant criticism, as we have previously highlighted. Questions have been raised over where the funding has flowed, with a particular focus on either regions, as shown in figure 1, and/or the party-political dimension, seen in figure 2.

Additionally, there are concerns over the appropriateness of the criteria underpinning the process – strategic fit, value for money, deliverability and place characteristics – in contrast to the first round that emphasised need for economic recovery, growth, improved transport connectivity and regeneration. Elsewhere, criticism has honed in on the costs involved in submitting bids, estimated at £30,000 per bid on average, with a number of applications appearing to have brought in professional grant writers. There are also wider questions over the scheme’s value for money, and a few raised eyebrows regarding some of the winning bids.

A sharply politicised process

All of this is set alongside wider arguments regarding the scale of financial support made available. The total value of the fund – £2.1 billion – is dwarfed by the £15 billion in cuts to local government finances over the last decade, which is exacerbated by a generational peak in inflation levels. With an election pencilled in for 2024, reports are that the third round of funding may well be brought forward. It is increasingly clear that after two rounds, both the current approach and methodology for addressing regional inequality in the UK have demonstrably politicised the whole debate around levelling up.

Figure 1: Levelling Up Funding Regional Distribution

Figure 2: Levelling Up Funding by Constituency

Lisa Nandy, Labour’s Shadow Secretary for Levelling Up drew headlines with the complaint that “…it’s like some kind of version of the Hunger Game”. But potentially the most damning critique of the levelling up programme came from the Conservative Party’s Andy Street, Mayor of the West Midlands Combined Authority [WMCA]. The WMCA, while successful in the first round, had its bid rejected in the second. Street’s response was highly critical in tone, arguing that the whole process amounted to an unedifying competitive tendering process pitting councils against one other:

“This episode is another example as to why Whitehall’s bidding and begging bowl culture is broken… The centralised system for London civil servants making local decisions is flawed. I cannot understand why the levelling up funding money was not devolved for local decision-makers to decide on what’s best for their areas.”

Street’s anger captures the extent to which the Conservative’s top-down, Whitehall-centric and highly divisive approach to levelling up has politicised the issue of regional policy to an almost unprecedented level.

How regional policy became a casualty of political struggles

Of course, the history of regional policy has always been a highly contentious issue and one of pronounced ideological disagreement. Labour have tended to emphasise strategic planning, from the 1945 Distribution of Industry Act, with its underlying moral imperative to spread economic activity equally across the country, to the Regional Development Agencies of the 2000s, with their attempts to coordinate investment at the regional level. In contrast, the Conservatives have preferred business-led initiatives that stimulate private sector activity, introducing Urban Development Corporations in the 1980s to encourage business investment in the inner city, and in the 2010s replacing Labour’s regional model with business-led Local Enterprise Partnerships.

These are just a few of the multitude of regional policy initiatives that have been created and scrapped over decades of tug-of-war between the two political parties. The push and pull of successive initiatives from central government has created a circular short-termism in this policy area, with politicisation driving policy churn. And this churn has been speeding up over recent decades, so that the chopping and changing of policy agendas has increased, alongside the ongoing renegotiation of central-local relations through devolution deals and competitive bidding.

The push and pull of successive initiatives from central government has created a circular short-termism in this policy area, with politicisation driving policy churn.

This acceleration of change in regional policy has in turn allowed for further politicisation. It is more important than ever for local politicians to have good connections with the government, and local leaders are acutely aware of the advantages of influential MPs. It is potentially even more advantageous for those in marginal seats. The electoral success of the “levelling up” slogan gives the government an important party-political motivation to demonstrate a tangible improvement to voters in marginal seats, and it is seemingly an irresistible temptation to use the levelling up fund to do so.

Local government reform – too much of a political gamble?

At the same time, there are political pressures coming up from local politicians, where an array of vested interests may stand in the way of key reforms to local government structures, not least in the roll-out of mayoral combined authorities. This is a problem for the current government, but could be an even bigger issue for Labour, which has a large local government base. One of the reasons that both political parties have shied away from wholesale reform of local government is the internal party struggles it would unleash. It is a political imperative for party leaders to avoid open conflict with the local politicians and activists who act as their electoral foot soldiers.

There are therefore two competing motivations when politicians make decisions about regional policy. On the one hand, it is clear that short-termism and unstable governance arrangements lead to less effective regional policy, not just in relation to tackling place-based inequalities, but across a whole range of policy areas. On the other hand, the politicisation of regional policy has gifted central politicians a new lever of control that can offer them various party-political advantages, while avoiding conflict with their local branches.

In the light of criticism from across the political spectrum, but most tellingly Andy Street’s critique of the “begging bowl” culture, and indeed the analysis laid out in the government’s own Levelling Up White Paper, it seems that the government is considering a shift towards more stable, devolved budgets. Meanwhile, the Labour Party have promised a major devolution of power if they were to win the next election, set-out most recently in their “five missions” to address short-termism, or what they label “sticking-plaster politics” and centralisation.

The real question is whether politicians of both colours will be able to resist the party-political pressures to politicise regional policy, and whether the politicisation of the devolution agenda will push this problem downwards. And yet, it seems we are now reaching a tipping point where a centralised, short-termist approach is simply no longer a viable political option.

The authors are affiliated with the ESRC’s Productivity Institute, on the project The UK Productivity-Governance Puzzle: Are UK’s Governing Institutions Fit for Purpose in the 21st Century?.

For more analysis of levelling up policy, browse all related blog posts here.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Mangopear Creative via Unsplash.